Heat engine

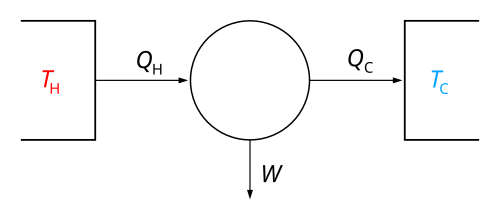

In engineering and thermodynamics, a heat engine converts heat energy to mechanical work by using the temperature difference between a hot "source" and a cold "sink". Heat is transferred from the source, through the "working body" of the engine, to the "sink", and in this process some of the heat changes into work by using the qualities of the gas or liquid inside the engine.

There are many kinds of heat engines. Each has a thermodynamic cycle. Heat engines are often named after the thermodynamic cycle they use, like the Carnot cycle. They often pick up everyday names, such as gasoline/petrol, turbine, or steam engines.

Internal combustion engines generate heat inside the engine itself. Other heat engines may absorb heat from an external source. Heat engines can be open to the air or sealed and closed off to the outside (This is called an Open or Closed cycle).

Overview

When scientists study heat engines they come up with ideas for engines that cannot actually be built. These are called ideal engines or cycles. Real heat engines are often confused with the ideal engines or cycles they attempt to mimic.

Typically when describing the physical device the term 'engine' is used. When describing the ideal the term 'cycle' is used.

One could say that the thermodynamic cycle is an ideal case of the mechanical engine. One could equally say that the model does not quite perfectly match the mechanical engine. However, much benefit is gained from the simplified models, and ideal cases they may represent.

In general terms, the larger the difference in temperature between the hot source and the cold sink, the more efficient the cycle or engine. On Earth, the cold side of any heat engine is limited to the air temperature of the place where the engine is.

Most efforts to improve the efficiency of heat engines goes into increasing the temperature of the heat source, but at very high temperatures the metal of the engine begins to go soft.

The efficiency of various heat engines proposed or used today ranges from 3 percent (97 percent waste heat) for the OTEC ocean power proposal through 25 percent for most automotive engines, to 45 percent for a supercritical coal plant, to about 60 percent for a steam-cooled combined cycle gas turbine. All of these processes gain their efficiency (or lack thereof) due to the temperature drop across them.

The least efficient, OTEC, uses the temperature difference of ocean water on the surface and ocean water from the depths, a small difference of perhaps 25 degrees Celsius, and so the efficiency must be low.

The most efficient, the combined cycle gas turbine burns natural-gas to heat air to nearly 1530 degrees Celsius, a large temperature difference of 1500 degrees Celsius, and so the efficiency can be very large when the steam-cooling cycle is added.[1]

Everyday examples

People mostly use heat engines where the heat comes from a fire that expands a working fluid (usually either water or air) and the heat sink is either a body of water or the atmosphere as in a cooling tower.

Familiar ones that use the expansion of heated gases include: the steam engine, the diesel engine, and the gasoline (petrol) engine in an automobile.

The Stirling engine is much rarer but is found in small models which can run off the heat of a hand.

One kind of toy heat engine is the drinking bird.

A bimetallic strip is a device that converts temperature into mechanical movement and is used in thermostats to control temperature. It is a heat engine that does not use a liquid or gas.

Heat Engine Media

Related pages

References

- ↑ "U.S. Department of Energy • Office of Fossil Energy, National Energy Technology Laborator: Advanced Turbine Systems. Advancing The Gas Turbine Power Industry" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-21. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- Kroemer, Herbert; Kittel, Charles (1980). Thermal Physics (2nd ed.). W.H. Freeman Company. ISBN 0-7167-1088-9.

- Callen, Herbert B. (1985). Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-86256-8.

Other websites

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- Heat Engine -Taftan Data

- Webarchive backup: Refrigeration Cycle Citat: "...The refrigeration cycle is basically the Rankine cycle run in reverse..."

- Red Rock Energy Solar Heliostats: Heat Engine Projects Citat: "...Choosing a Heat Engine..."

- Overview of heat engine types Archived 2007-06-21 at the Wayback Machine

- The rotary piston array machine

- The gyroscope combustion motor Archived 2007-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- The external combustion air engine