Ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet (Danish: «Indlandsis», meaning «inland ice»), usually called continental glacier and sometimes ice shell or ice layer, is a large mass of glacier ice with an average thickness of over 2 km that covers a large continental area in the polar regions of the Earth. They're located at extreme latitudes with a conventional area of more than 50,000 square kilometres (19,000 sq mi).[1][2] In other geologic time spans, there was a major number and they were covering an larger area, but currently they only cover Antarctica and Greenland. This concept might not be confused with the sea ice (the floating layer of ice of variant extension that forms in the polar seas), neither the ice shelf (barrier of ice of glacier origin that spans from the coast to the inner of the ocean) nor the polar cap.

Ice sheets are larger than ice shelves or alpine glaciers. Masses of ice covering less than 50,000 km2 are called an ice cap. An ice cap will usually feed a series of glaciers around its periphery.

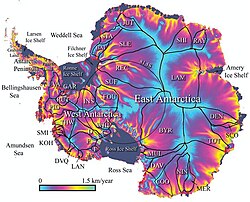

Although the surface is cold, the base of an ice sheet is generally warmer due to geothermal heat. In some places, melting occurs and the melt-water lubricates the ice sheet so that it flows it rapidly. This process produces fast flowing channels inside the ice sheet: these are ice streams.

The two current ice sheets are relatively young in geological terms. The Antarctic ice sheet first formed in the early Oligocene. It retreated and advanced many times until the Pliocene, when it came to occupy almost all of Antarctica. The Greenland ice sheet did not develop at all until the late Pliocene, but apparently developed very quickly. This had the unusual effect of allowing fossils of plants that once grew on present-day Greenland to be much better preserved than with the slowly forming Antarctic ice sheet.

Earth's current two ice sheets

Antarctic ice sheet

The Antarctic ice sheet is the largest single mass of ice on Earth. It covers an area of almost 14 million km2 and contains 30 million km3 of ice. Around 90% of the fresh water on the Earth's surface is held in this ice sheet. If all of it were to melt, it would cause sea levels to rise by 58 metres.[3] The ice sheet first formed in the early Oligocene. It retreated and advanced many times until the Pliocene, when it came to occupy almost all of Antarctica.

Greenland ice sheet

The Greenland ice sheet covers about 82% of the surface of Greenland, a part of Denmark. Satellite images from NASA show that it is melting at a rate of about 239 cubic kilometres (57.3 cubic miles) each year.[4][5] If all of it melted, it would cause sea levels to rise by 7.2 metres.[3] The ice sheet did not develop at all until the late Pliocene, but apparently developed very quickly. This had the unusual effect of allowing fossils of plants that once grew on present-day Greenland to be much better preserved than with the slowly forming Antarctic ice sheet.

Ice Sheet Media

Greenland ice sheet as seen from space

The motion of ice in Antarctica

The collapse of the Larsen B ice shelf had profound effects on the velocities of its feeder glaciers.

Distribution of meltwater hotspots caused by ice losses in Pine Island Bay, the location of both Thwaites (TEIS refers to Thwaites Eastern Ice Shelf) and Pine Island Glaciers.

A collage of footage and animation to explain the changes that are occurring on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, narrated by glaciologist Eric Rignot

If MICI can occur, the structure of the glacier embayment (viewed from the top) would do a lot to determine how quickly it may proceed. Bays which are deep or narrow towards the exit would experience much less rapid retreat than the opposite

Carbon stores and fluxes in present-day ice sheets (2019), and the predicted impact on carbon dioxide (where data exists). Estimated carbon fluxes are measured in Tg C a−1 (megatonnes of carbon per year) and estimated sizes of carbon stores are measured in Pg C (thousands of megatonnes of carbon). DOC = dissolved organic carbon, POC = particulate organic carbon.

Related pages

References

- ↑ "Glossary of Important Terms in Glacial Geology". Archived from the original on 2006-08-29. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ "American Meteorological Society, Glossary of Meteorology". Archived from the original on 2012-06-23. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Some physical characteristics of ice on Earth Archived 2007-12-16 at the Wayback Machine, Climate Change 2001: Working Group I: The Scientific Basis. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

- ↑ Rasmus Benestad et al.: The Greenland Ice. Realclimate.org 2006

- ↑ Greenland melt 'speeding up', BBC News, 11 August 2006