Infinity

Infinity ([math]\displaystyle{ \infty }[/math]) is a mathematical concept which is about things that never end. It is written in a single digit. Infinity means many different things, depending on when it is used. The word is from Latin origin, meaning "without end". Infinity goes on forever, so sometimes space, numbers, and other things are said to be 'infinite', because they never come to a stop.

Infinity is usually not an actual number, but it is sometimes used as one. Infinity often says how many there is of something, instead of how big something is. For example, there are infinitely many whole numbers (called integers), but there is no integer which is infinitely big. But different kinds of math have different kinds of infinity. So its meaning often changes.

There are two kinds of infinity: potential infinity and actual infinity. Potential infinity is a process that never stops. For example, adding 10 to a number. No matter how many times 10 is added, 10 more can still be added. Actual infinity, on the other hand, refers to objects that are accepted as infinite entities (such as transfinite numbers).[1]

Infinity in Mathematics

Mathematicians have different sizes of infinity and three different kinds of infinity.[2]

Counting infinity

The number of things, beginning with 0, 1, 2, 3, ..., to include infinite cardinal numbers. There are many different cardinal numbers. Infinity can be defined in one of two ways: Infinity is a number so big that a part of it can be of the same size; Infinity is larger than all of the natural numbers. There is a smallest infinite number, countable infinity. It is the counting number for all of the whole numbers. It is also the counting number of the rational numbers. The mathematical notation is the Hebrew letter aleph with a subscript zero; [math]\displaystyle{ \aleph_0 }[/math]. It is spoken "aleph null".[3]

It was a surprise to learn that there are larger infinite numbers.[2] The number of real numbers, that is, all numbers with decimals, is larger than the number of rational numbers, the number of fractions. This shows that there are real numbers which are not fractions. The smallest infinite number greater than [math]\displaystyle{ \aleph_0 }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \aleph_1 }[/math] (aleph one). The number of mathematical functions is the next infinite cardinal number, [math]\displaystyle{ \aleph_2 }[/math]. And these numbers, called aleph numbers,[4] go on without end.

Ordering infinity

A different type of infinity are the ordinal numbers, beginning "first, second, third, ...". The order "first, second, third, ..." and so on to infinity is different from the order ending "..., third, second, first". The difference is important for mathematical induction. The simple first, second, third, ... has the mathematical name: the Greek letter omega with subscript zero: [math]\displaystyle{ \omega_0 }[/math].[4] (Or simply omega [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math].) The infinite series ending "... third, second, first" is [math]\displaystyle{ ^*\omega }[/math].

The real line and complex plane

The third type of infinity has the symbol [math]\displaystyle{ \infty }[/math]. This is treated as addition to the real numbers or the complex numbers. It is the result of division by zero, or to indicate that a series is increasing (or decreasing) without bound. The series 1, 2, 3, ... increases without upper bound. This is written: the limit is [math]\displaystyle{ +\infty }[/math]. In calculus, the integral over all real numbers is written: [math]\displaystyle{ \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} f(x)\,dx }[/math]

The arithmetic of infinity

Each kind of infinity has different rules.

Addition, multiplication, exponentiation

[math]\displaystyle{ \aleph_0 + 1 = 1 + \aleph_0 = \aleph_0 + \aleph_0 = \aleph_0 }[/math] Addition with "alephs" is commutative.

[math]\displaystyle{ 2 \times \aleph_0 = \aleph_0 \times 2 = \aleph_0 \times \aleph_0 = \aleph_0 }[/math] Multiplication with "alephs" is commutative.

[math]\displaystyle{ \aleph_0 + \aleph_1 = \aleph_1 \times \aleph_0 = \aleph_1 }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ {\aleph_0} ^ {\aleph_0} \gt 3 ^ {\aleph_0} \gt 2 ^ {\aleph_0} = \aleph_1 }[/math].[2]

[math]\displaystyle{ 1 + \omega = \omega \neq \omega +1 }[/math]. Addition with "omegas" is not commutative.

[math]\displaystyle{ 2 \times \omega = \omega \neq \omega \times 2 }[/math]. Multiplication with "omegas" is not commutative.

[math]\displaystyle{ \omega + \omega = \omega \times 2 }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \omega ^ \omega \gt 3 ^ \omega \gt 2 ^ \omega }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ x + \infty = \infty = \infty + \infty = \infty \times \infty = 2 ^ \infty }[/math]

Subtraction, division

Division by infinity (for example, with omegas or alephs) is not meaningful. Subtraction with infinity is not meaningful.

Infinity Media

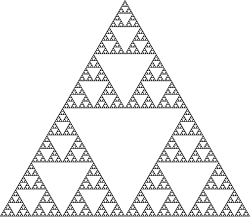

The Sierpiński triangle contains infinitely many (scaled-down) copies of itself.

By stereographic projection, the complex plane can be "wrapped" onto a sphere, with the top point of the sphere corresponding to infinity. This is called the Riemann sphere.

The first three steps of a fractal construction whose limit is a space-filling curve, showing that there are as many points in a one-dimensional line as in a two-dimensional square

Related pages

- Countable set

- Eternity

- Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel

- Riemann sphere, complex plane with a point at infinity

- Uncountable set

References

- ↑ "The Definitive Glossary of Higher Mathematical Jargon: Infinite". Math Vault. 2019-08-01. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 To simply, we will assume several axioms like the Axiom of choice and the Generalized continuum hypothesis.

- ↑ "Transfinite number | mathematics". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Comprehensive List of Set Theory Symbols". Math Vault. 2020-04-11. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

Other websites

- A Crash Course in the Mathematics of Infinite Sets Archived 2010-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, by Peter Suber. From the St. John's Review, XLIV, 2 (1998) 1-59. The stand-alone appendix to Infinite Reflections, below. A concise introduction to Cantor's mathematics of infinite sets.

- Infinite Reflections Archived 2009-11-05 at the Wayback Machine, by Peter Suber. How Cantor's mathematics of the infinite solves a handful of ancient philosophical problems of the infinite. From the St. John's Review, XLIV, 2 (1998) 1-59.

- Infinity, Principia Cybernetica Archived 2010-08-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Hotel Infinity Archived 2004-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- The concepts of finiteness and infinity in philosophy