Countable set

In mathematics (particularly set theory), a countable set is a set whose elements can be counted. A set with one thing in it is countable, and so is a set with one hundred things in it. A set with all the natural numbers (counting numbers) in it is countable too. This is because even if it is infinite, someone who counts forever would not miss any of the numbers. The sets which has the same size as the natural numbers are therefore called countably infinite. The size of these sets are then written as [math]\displaystyle{ \aleph_0 }[/math](aleph-null)—the first of the aleph numbers.[1] Sometimes when people say 'countable set' they mean countable and infinite.[2] Georg Cantor coined the term.

Examples of countable sets

Countable sets include all sets with a finite number of members, no matter how many.

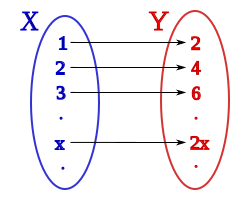

Countable sets also include some infinite sets, such as the natural numbers. Since it is impossible to actually count infinite sets, we consider them countable if we can find a way to list them all without missing any. The natural numbers have been nicknamed "the counting numbers", since they are what we usually use to count things with.

You can count the natural numbers with [math]\displaystyle{ ({1, 2, 3...})\,\! }[/math]

You can count the whole numbers with [math]\displaystyle{ ({0, 1, 2, 3...})\,\! }[/math]

You can count the integers with [math]\displaystyle{ ({0, 1, -1, 2, -2, 3, -3...})\,\! }[/math]

You can count the square integer numbers with [math]\displaystyle{ ({0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, ...})\,\! }[/math]

A more-complex example

The rational numbers are also countable, but its counting becomes tricky. We can't just list the fractions as (0/1, 1/1, -1/1, 2/1, -2/1...) since we will never get to 1/2 this way. However, we can list all of the rational numbers in the form of a table. The horizontal rows are the numerators, while the vertical columns are the denominators. We can then zigzag through the list, starting at 1/1, then 2/1, then 1/2, then 1/3, then 2/2, then 3/1, then 4/1, then 3/2, then 2/3, etc. If we keep this up, we will get to all of the numbers on the table in due time. Each time we hit a new rational number that is new, we add it to the list of counted numbers. We don't want to count numbers twice, so when we hit 3/6, for example, we can skip it, because we already counted the rational number 1/2. In this way, we produce an infinite list with all the rational numbers. Therefore, the rational numbers are countable.

Not all counting schemes will yield a countable list

Suppose the integers are counted differently, as

- [math]\displaystyle{ ({0, 1, 2, 3, .... -1,-2, -3, ...})\,\! }[/math]

This does not prove that the integers are uncountable, but it does illustrate what one might call a "failed" effort to count a set, because it is never possible to reach [math]\displaystyle{ -1 }[/math]. Not all sets are countable. For example, the interval [math]\displaystyle{ (0,1) }[/math] and the set of real numbers can be proven to be uncountable.[3]

Countable Set Media

The Cantor pairing function assigns one natural number to each pair of natural numbers

Related pages

References

- ↑ "Comprehensive List of Set Theory Symbols". Math Vault. 2020-04-11. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Countable Set". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- ↑ "9.3: Uncountable Sets". Mathematics LibreTexts. 2017-09-20. Retrieved 2020-09-06.