Chemical cell

A chemical cell converts chemical energy into electrical energy. Most batteries are chemical cells. A chemical reaction takes place inside the battery and causes electric current to flow.

There are two main types of batteries - those that are rechargeable and those that are not.

A battery that is not rechargeable will give electricity until the chemicals in it are used up. Then it is no longer useful. It can be rightly called 'use and throw'.

A rechargeable battery can be recharged by passing electric current backwards through the battery; it can then be used again to produce more electricity. It was Gaston Plante, a French scientist who invented these rechargeable batteries in 1859.

Batteries come in many shapes and sizes, from very small ones used in toys and cameras, to those used in cars or even larger ones. Submarines that aren't nuclear submarines require very large batteries.

Types of chemical cells

- Simple cell

- Dry cell

- Wet cell

- Fuel cell

- Solar cell

- Electric cell

Electrochemical cells

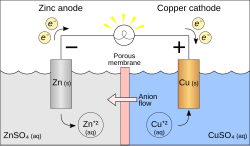

An extremely important class of oxidation and reduction reactions are used to provide useful electrical energy in batteries. A simple electrochemical cell can be made from copper and zinc metals with solutions of their sulphates. In the process of the reaction, electrons can be transferred from the zinc to the copper through an electrically conducting path as a useful electric current.

An electrochemical cell can be created by placing metallic electrodes into an electrolyte where a chemical reaction either uses or generates an electric current. Electrochemical cells which generate an electric current are called voltaic cells or galvanic cells, and common batteries consist of one or more such cells. In other electrochemical cells an externally supplied electric current is used to drive a chemical reaction which would not occur spontaneously. Such cells are called electrolytic cells.

Voltaic cells

An electrochemical cell which causes external electric current flow can be created using any two different metals since metals differ in their tendency to lose electrons. Zinc more readily loses electrons than copper, so placing zinc and copper metal in solutions of their salts can cause electrons to flow through an external wire which leads from the zinc to the copper. As a zinc atom provides the electrons, it becomes a positive ion and goes into aqueous solution, decreasing the mass of the zinc electrode. On the copper side, the two electrons received allow it to convert a copper ion from solution into an uncharged copper atom which deposits on the copper electrode, increasing its mass. The two reactions are typically written

The letters in parentheses are just reminders that the zinc goes from a solid (s) into a water solution (aq) and vice versa for the copper. It is typical in the language of electrochemistry to refer to these two processes as "half-reactions" which occur at the two electrodes.

|

|

In order for the voltaic cell to continue to produce an external electric current, there must be a movement of the sulfate ions in solution from the right to the left to balance the electron flow in the external circuit. The metal ions themselves must be prevented from moving between the electrodes, so some kind of porous membrane or other mechanism must provide for the selective movement of the negative ions in the electrolyte from the right to the left.

Energy is required to force the electrons to move from the zinc to the copper electrode, and the amount of energy per unit charge available from the voltaic cell is called the electromotive force (emf) of the cell. Energy per unit charge is expressed in volts (1 volt = 1 joule/coulomb).

Clearly, to get energy from the cell, you must get more energy released from the oxidation of the zinc than it takes to reduce the copper. The cell can yield a finite amount of energy from this process, the process being limited by the amount of material available either in the electrolyte or in the metal electrodes. For example, if there were one mole of the sulfate ions SO42- on the copper side, then the process is limited to transferring two moles of electrons through the external circuit. The amount of electric charge contained in a mole of electrons is called the Faraday constant, and is equal to Avogadro's number times the electron charge:

The energy yield from a voltaic cell is given by the cell voltage times the number of moles of electrons transferred times the Faraday constant.

Chemical Cell Media

A demonstration electrochemical cell setup resembling the Daniell cell. The two half-cells are linked by a salt bridge carrying ions between them. Electrons flow in the external circuit.

The cell emf Ecell may be predicted from the standard electrode potentials for the two metals. For the zinc/copper cell under the standard conditions, the calculated cell potential is 1.1 volts.

Simple cell

A simple cell typically has plates of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) in dilute sulphuric acid. The zinc dissolves and bubbles of hydrogen appear on the copper plate. These hydrogen bubbles interfere with the passage of current so a simple cell can only be used for a short time. To provide a steady current, a depolarizer (an oxidizing agent) is needed to oxidize the hydrogen. In the Daniel cell, the depolarizer is copper sulphate, which exchanges the hydrogen for copper. In the Leclanche battery, the depolarizer is manganese dioxide, which oxidizes the hydrogen to water.

Daniel cell

English chemist John Frederick Daniell developed a voltaic cell in 1836 which used zinc and copper and solutions of their ions.

- Key

- Zinc rod = negative terminal

- H2SO4 = dilute sulphuric acid electrolyte

- Porous pot separates the two liquids

- CuSO4 = copper sulphate depolarizer

- Copper pot = positive terminal