Chess notation

Chess notation is a method for writing down chess moves: after a player makes a move, both players write it down. This is compulsory in all organized chess events.[1][2]

The system must have these elements: the move number, the piece moved, the square it starts from (optional), the square it goes to, and other relevant information such as captures, and castles.[3]p275 There are other notations for recording positions.

There have been ways of describing moves from quite early on. Manuscripts with move descriptions are known in Arabic (9th century) and from Europe (13th century).[3]p275 These early notations are usually quite cumbersome; "The pawn of the king forward two houses".[4]p229; 469; 848 This kind of notation is called descriptive. In a descriptive notation each player describes squares from his own point of view, e.g. 1 P–K4 P–K4. A notation which uses labels for the ranks and files is called algebraic. In this notation a square has only one label, e.g. 1 e4 e5.

Algebraic notation

The moves of a chess game are written down by using a special notation.[1]Article 8 and Appendix E Usually algebraic chess notation is used.[5] In algebraic notation, each square has one name (whether you are looking from White's side of the board or Black's). Here, moves are written in the format of: abbreviation of the piece moved – file where it moved – rank where it moved. For example, Qg5 means "queen moves to the g-file and 5th rank" (that is, to the square g5). If there are two pieces of the same type that can move to the same square, one more letter or number is added to show the file or rank from which the piece moved, e.g. Ngf3 means "knight from the g-file moves to the square f3". The letter P showing a pawn is not used, so that e4 means "pawn moves to the square e4".

If the piece makes a capture, "x" is written before the square in which the capturing piece lands on.[6] Example: Bxf3 means "bishop captures on f3". When a pawn makes a capture, the file from which the Pawn left is used in place of a piece initial. For example: exd5 means "pawn captures on d5."

If a pawn moves to its eighth rank, getting a promotion, the piece chosen is written after the move, for example e1Q or e1=Q. Castling is written by the special notations 0–0 for kingside castling and 0–0–0 for queenside. A move which places the opponent's king in check normally has the notation "+" added. Checkmate can be written as # or ++. At the end of the game, 1–0 means "White won", 0–1 means "Black won" and ½-½ is a draw.

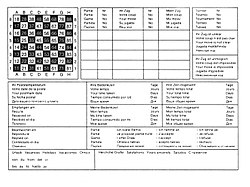

Chess moves can also be shown with punctuation marks and other annotation symbols.[6] For example: ! means a good move, !! means a very good move, ? means a bad move, ?? a very bad move (sometimes called a blunder), !? a creative move that may be good, and ?! a doubtful move. For example, one kind of a simple "trap" known as the Scholar's mate, as in the diagram to the right, may be recorded in full notation:

1. e2-e4 e7-e5

2. Qd1-h5?! Nb8-c6

3. Bf1-c4 Ng8-f6?? (3...Qe7 is better)

4. Qh5xf7# 1–0

Here is a famous short game in the more usual short notation:

- Réti v Tartakower, Vienna 1910

- e4 c6

- d4 d5

- Nc3 dxe4

- Nxe4 Nf6

- Qd3?! e5?!

- dxe5 Qa5+

- Bd2 Qxe5

- 0-0-0 Nxe4??

- Qd8+!! Kxd8

- Bg5+ Kc7

- Bd8# 1–0

Figurine notation

♖ ♜; ♘ ♞; ♗,♝; ♕,♛; ♔, ♚

This is algebraic notation with little figurines instead of initial letters for the pieces. Figurine notation is used in print and computer chess. Since it avoids initial letters for pieces, it is more international.

- Réti v Tartakower, Vienna 1910

- e4 c6

- d4 d5

- ♘c3 dxe4

- ♘xe4 ♞f6

- ♕d3?! e5?!

- dxe5 ♛a5+

- ♗d2 ♛xe5

- 0-0-0 ♞xe4??

- ♕d8+!! ♚xd8

- ♗g5+ ♚c7

- ♗d8# 1–0

Notation for positions

In addition to the Forsyth notation, positions may be recorded in this simple fashion:

- White: Kf2; Qe3; Rf6, Rf7; Ne2; pawns d4, e5, h3.

- Black: Kc8; Qa2; Rf8, Rc7; Ba6; pawns d5, e6, f7, h4. White to play.

Chess Notation Media

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Laws of Chess". FIDE. Retrieved 2008-11-26.

- ↑ Reuben, Stewart 2005. The chess organiser's handbook. 3rd ed, incorporating the FIDE Laws of Chess. Harding Simpole, Devon.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hooper D. and Whyld K. 1992. The Oxford companion to chess. 2nd ed, Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Murray H.J.R. 1913. The history of chess. Oxford. reprint ISBN 0-936317-01-9

- ↑ See paragraph E. Algebraic notation in:

"E.I.01B. Appendices". FIDE. Retrieved 2008-11-26. - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Roger McIntyre. "Logical chess". Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.