Great Vowel Shift

The Great Vowel Shift (GVS) was a period of shifts in the pronunciation of vowels in the English language that took place approximately from the 15th century (the late Middle English period) to the 18th century (the Early Modern English period).[1][2] It is the main reason for English words often sounding different from how they are spelled. The Great Vowel Shift was named by the Danish linguist Otto Jespersen, who studied it.

Furthermore, coinciding with the development of print, the Great Vowel Shift and the increasing production of printed materials have brought about the standardisation of English as we know it today. [3]

Changes

The change Great Vowel Shift is often divided into two phases (with a third period in Early Modern English with less critical and more minor changes) and varied slightly in differenct English dialects. It concerned long and short vowels and diphthongs. It started in the 1400s and continued for several centuries. The pronunciation of several consonants changed as well, which is sometimes described by scholars when discussing the GVS.

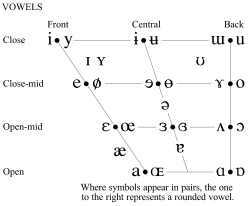

During Middle English, there were five short and seven long vowels. Through the GVS, the long vowels /i:/ and /u:/ gained counterparts that they had not had before, which restored the balance in the vowel system. The attempt to achieve that balance is thought to be one of the reasons for the start of the GVS. Other theories are the pull-chain and the push-chain theories.

- The pull-chain theory suggests that the first to leave their positions were the higher vowels, which then pulled the lower vowels to move as well.

- The push-chain theory offers the opposite solution and suggests that the lower vowels were the first to move and that after they were raised, they pushed the higher vowels up from their previous positions.

The change of pronunciation during the GVS affected long stressed vowels. Therefore, “y” in “only” did not change pronunciation because it is unstressed, but the same vowel changed its pronunciation in the word “my” because it is stressed.[4] The place of pronunciation in the mouth changed it to be pronounced in a higher place in the mouth.[5]

It is important to note that distinguishing the Middle English pronunciation is just an approximation done by scholars because there are no recordings of the spoken language from that period.[4]

Examples

| Word | Long vowel pronunciation | |

|---|---|---|

| Late Middle English

(before the GVS) |

Modern English

(after the GVS) | |

| bite | /iː/ | /aɪ/ |

| meet | /eː/ | /iː/ |

| meat | /ɛː/ | |

| serene | ||

| mate | /aː/ | /eɪ/ |

| out | /uː/ | /aʊ/ |

| boot | /oː/ | /uː/ |

| boat | /ɔː/ | /oʊ/ |

| stone | ||

| Word | Short vowel pronunciation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Late Middle English

(before the GVS) |

Modern English

(after the GVS) |

||

| glad | /a/ | /æ/ | |

| clap | |||

| call | /a/ | /ɔː/ | when followed by "L" |

| also | |||

| Word | Diphtong pronunciation | |

|---|---|---|

| Late Middle English

(before the GVS) |

Modern English

(after the GVS) | |

| day | /æj/ | /eɪ/ |

| they | ||

| law | /ɑw/ | /ɔː/ |

| knew | /ew/ | /juː/ |

| dew | /ɛw/ | |

| know | /ɔw/ | /oʊ/ |

Historical division

Most generally, the researchers of the Great Vowel Shift have divided it into two phases, which coincidentally correspond with the periods of writings of two famous English writers: Geoffrey Chaucer and William Shakespeare. Consequently, Chaucer’s and Shakespeare’s writings are often used as the most representative examples changes cuased by the GVS.

Social and cultural influences

The exact pinpointing of the period of the Great Vowel Shift and the reason for its occurrence remain unknown. However, there are several theories that are the most frequent, the most widely accepted and are interconnected through the notions of social emancipation and elitism.

- The plague, or the Black Death, fast-tracked the levels of migration in England, with London and the rest of Southern England as the final destinations. The explanation for that choice of destination of migration might be that although the infection was present everywhere throughout England, the death rates differed, with the Southern England as the area with the lowest levels of casualties. The reason behind that is that is area had been mostly inhabited by the royals and the aristocracy, which meant better hygienic conditions and higher levels of health care and essentially presentied better chances to resist, counter and overcome the plague.[3] Furthermore, the surplus of inhabitants in the capital might have fuelled the urge in the original inhabitants to differentiate themselves from and place themselves above the migrants culturally and socially through a “more advanced” pronunciation of vowels.

- The Hundred Years' War caused the presence of people from France and, with it, the influence of French loan words during the Middle English period, which caused thousands of borrowings (mainly vocabulary connected to the government, war, church, law, cuisine and clothes), which transformed the English language, including its pronunciation.[7]

- Another factor might have been the middle-class hypercorrection as an effort to imitate the aristocracy’s more prestigious French pronunciation, as French was the language of the aristocracy, diplomacy and law and was spoken by the ruling class. Inversely, the shift might have also been influenced by anti-French sentiment in England caused by the wars with France and by the English people’s efforts of distancing themselves from the French way of speaking.[8]

Great Vowel Shift Media

Reconstructed Middle English, Early Modern English, and Modern English pronunciation of bite, showing how long vowels changed in pronunciation during the Great Vowel Shift.

Reconstructed Middle English, Early Modern English, and Modern English pronunciation of out, showing how long vowels changed in pronunciation during the Great Vowel Shift.

Reconstructed Middle English, Early Modern English, and Modern English pronunciation of meet, showing how long vowels changed in pronunciation during the Great Vowel Shift.

Reconstructed Middle English, Early Modern English, and Modern English pronunciation of boot, showing how long vowels changed in pronunciation during the Great Vowel Shift.

Reconstructed Middle English, Early Modern English, and Modern English pronunciation of meat, showing how long vowels changed in pronunciation during the Great Vowel Shift.

Reconstructed Middle English, Early Modern English, and Modern English pronunciation of boat, showing how long vowels changed in pronunciation during the Great Vowel Shift.

Reconstructed Middle English, Early Modern English, and Modern English pronunciation of mate, showing how long vowels changed in pronunciation during the Great Vowel Shift.

References

- ↑ Dobson E.J. 1968. English Pronunciation 1500–1700. 2 vols, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press. (vol. 2, 594–713 for discussion of long stressed vowels).

- ↑ Nordquist, Richard 2018. [1]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Crystal, David (2010). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Harvard's Geoffrey Chaucer Website". Retrieved 1 Feb 2023.

- ↑ Menzer, Melinda J. "The Great Vowel Shift". Retrieved 1 Feb 2023.

- ↑ "Great Vowel Shift".

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chamonikolasová, Jana (2014). A Concise History of English. Brno: Masaryk University.

- ↑ "What Was the Great Vowel Shift and Why Did it Happen?". 17 May 2022. Retrieved 1 Feb 2023.