Diode

A diode is an electronic component with two electrodes (connectors) that allows electricity to go through it in one direction and not the other direction.

Diodes can be used to turn alternating current into direct current (Diode bridge). They are used in power supplies and sometimes to decode amplitude modulation radio signals (like in a crystal radio). Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are a type of diode that produce light.

Today, the most common diodes are made from semiconductor materials such as silicon or sometimes germanium.

History

The first types of diodes were called Fleming valves. They were vacuum tubes. They were inside a glass tube (much like a lightbulb). Inside the glass bulb there was a small metal wire and a large metal plate. The small metal wire would heat up and emit electricity, which was captured by the plate. The large metal plate was not heated, so electricity could go in one direction through the tube but not in the other direction. Fleming valves are not used much anymore because they have been replaced by semiconductor diodes, which are smaller than Fleming valves. Thomas Edison also discovered this property when working on his light bulbs.

Construction

Semiconductor diodes are made of two types of semiconductors connected to each other. One type has atoms with extra electrons (called the n-side). The other type has atoms that want electrons (called the p-side). Because of this, the electricity will flow easily from the side with too many electrons to the side with too few. However, electricity will not flow easily in the reverse direction. These different types are made by doping (semiconductor). Silicon with arsenic dissolved in it makes a good n-side semiconductor, while silicon with aluminum dissolved in it makes a good p-side semiconductor. Other chemicals can also work.

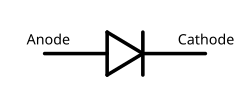

The connector to the n-side is called the cathode, the connector to the p-side is called the anode.

Function of a diode

Positive voltage at p-side

If you give positive voltage to the p-side and negative voltage to the n-side, the electrons in the n-side will want to go to the positive voltage at the p-side and the holes of the p-side will want to go to the negative voltage at the n-side. Because of this, current flow is able to exist, but it takes a certain amount of voltage to get this started (very small amount of voltage is not enough to get the electric current to flow). This is called the cut-in voltage. The cut-in voltage of a silicon diode is at about 0.7 V. A germanium diode needs a cut-in voltage at about 0.3 V.

Negative voltage at p-side

If you instead give negative voltage to the p-side and positive voltage to the n-side, the electrons of the n-side want to go to the positive voltage source instead of the other side of the diode. Same thing happens on the p-side. So, current will not flow between the two sides of the diode. Increasing the voltage will eventually force electric current to flow (this is the break-down voltage). Many diodes will be destroyed by a reverse flow but some are made that can survive it.

Influence of temperature

When the temperature increases, the cut-in voltage goes down. This makes it easier for electricity to pass through the diode.

Types of diodes

There are many types of diodes. Some have very specific uses and some have a variety of uses.

Symbols

Here are some common semiconductor diode symbols used in schematic diagrams:

|

|

|

|

| Diode | Zener Diode | Schottky diode | Tunnel diode |

|

| ||

| Light-emitting diode | Photodiode | Varicap | Silicon controlled rectifier |

Standard rectifier diode

This changes A/C (alternating current, like in a wall plug in a house) to D/C (direct current, used in electronics). The standard rectifier diode has specific requirements. It should handle high current, not be much affected by temperature, have a low cut-in voltage and support quick changes in the direction of current flow. Modern analog and digital electronics use such rectifiers.

Light-Emitting Diode

An LED produces light when electricity flows through it. It is a longer lasting and more efficient way of creating light than incandescent light bulbs. Depending on how it was made, the LED can make different colors. LEDs were first used in the 1970's. The light-emitting diode may eventually replace the light bulb as developing technology makes it brighter and cheaper (it is already more efficient and lasts longer). In the 1970's the LEDs were used to show numbers in appliances such as calculators, and as a way to show the power was on for larger appliances.[1]

Photodiode

A photodiode is a photo detector (the opposite of a light-emitting diode). It responds to light that comes in. Photodiodes have a window or optical fiber connection, which lets light in to the sensitive part of the diode. Diodes usually have strong resistance; the light reduces the resistance.[Analog Electronics (Mango Engineer) 1]

Zener Diode

A zener diode is like a normal diode, but instead of being destroyed by a big reverse voltage, it lets electricity through. The voltage needed for this is called the breakdown voltage or Zener voltage.[2] Because it is built with a known breakdown voltage it can be used to supply a known voltage.

Varactor Diode

The varicap or varactor diode is used in many appliances. It uses the region between the p-side and n-side of the diode where electrons and holes balance each other. This is called the depletion zone. By changing the amount of reverse voltage, the size of the depletion zone changes. There is some capacitance in this area, and it changes based on the size of the depletion zone. This is called variable capacitance, or varicap for short.[3] It is used in PLLs (Phase-locked loops) which are used to control the high-speed frequency a chip runs at.

Step-Recovery-Diode

The symbol is the symbol of a diode with a kind of snag. It is used in circuits with high frequencies up to GHz. It turns off very quickly when the forward voltage stops. It uses the current that flows after the polarity was reversed to do this.

PIN Diode

The construction of this diode has an intrinsic (normal) layer between the n- and the p-sides. At slower frequencies, it acts much like a standard diode. But at high speeds it can not keep up with fast changes and starts to act like a resistor. The intrinsic layer also lets it handle high power inputs, and can be used as a photodiode.

Schottky diode

The symbol of this is the diode symbol, with an ‘S’ at the peak. Instead of both sides being a semiconductor (like silicon), one side is metal, like aluminum or nickel. This reduces the cut-in voltage to about 0.3 volt. This is about half of the threshold voltage of a usual diode. The function of this diode is that no minority carriers are injected - the n-side only has holes, not electrons, and the p-side only has electrons, not holes.[1] Because this is cleaner, it can react faster, without diffusion capacitance that can slow it down. It also creates less heat and is more efficient. But it does has some current leakage with reverse voltage.

When a diode switches from moving current to not moving current, this is known as switching. It takes dozens of nanoseconds in a typical diode; this creates some radio noise, which temporarily degrades radio signals. The Schottky diode switches in a small fraction of that time, less than a nanosecond.

Tunnel diode

In the symbol of the tunnel diode there is a kind of additional square bracket at the end of the usual symbol.

A tunnel diode consists of a highly doped pn-junction. Because of this high doping, there is only a very narrow gap where the electrons are able to pass through. This tunnel-effect appears in both directions. After a certain quantity of electrons have passed, the current through the gap decreases, until the normal current through the diode at the threshold voltage begins. This causes an area of a negative resistance. These diodes are used to deal with really high frequencies (100 GHz). It is also resistant to radiation, so they are used in spacecraft. They are also used in microwaves and refrigerators.[4]

Backward diode

The symbol has at the end of the diode a sign that looks like a big I. It is made similar to the tunnel diode, but the n- and the p-layer are not doped as high. It allows current to flow backwards with small negative voltages. It can be used to rectify low voltages (less than 0.7 volts).

Silicon-Controlled Rectifier (SCR)

Instead of two layers like a normal diode, this has four layers, it is basically two diodes put together, with a gate in the middle. When voltage goes between the gate and the cathode the lower transistor will turn on. This lets the current go through, which activates the upper transistor, and then the current will not need to be turned on by a gate voltage.[5]

Diode Media

Various semiconductor diodes. Left: A four-diode bridge rectifier. Next to it is a 1N4148 signal diode. On the far right is a Zener diode. In most diodes, a white or black painted band identifies the cathode into which electrons will flow when the diode is conducting. Electron flow is the reverse of conventional current flow.

Forward current–voltage curve of 4 common diodes.

Structure of a vacuum tube diode. The filament itself may be the cathode, or more commonly (as shown here) used to heat a separate metal tube which serves as the cathode.

A p–n junction diode in low forward bias mode. The depletion width decreases as voltage increases. Both p and n junctions are doped at a 1e15/cm3 doping level, leading to built-in potential of ~0.59V. Observe the different quasi Fermi levels for conduction band and valence band in n and p regions (red curves).

Current–voltage characteristic of a p–n junction diode showing three regions: breakdown, reverse biased, forward biased. The exponential's "knee" is at Vd. The leveling off region which occurs at larger forward currents is not shown.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kant, Kamal (3 December 2023). "Fundamentals of Diode, P-N Junction Diode Working and VI Characteristics". Mango Engineer. Archived from the original on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ↑ "Zener Diode". Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ↑ J.B. Calvert (2002-02-15). "Varactors". Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ↑ "Learn About LEDs". Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ↑ "The Silicon Controlled Rectifier" (PDF). .PDF. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

Other websites

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- The Unusual Diode FAQ Archived 2009-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Analog Electronics (Mango Engineer)". 3 December 2023. Retrieved 27 December 2023.