Mammaliaformes

Mammaliaformes ("mammal-like") is a clade which contains the mammals and their closest extinct relatives.[1]

| Mammaliaformes Temporal range: Upper Triassic–Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Adelobasileus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Unrecognized taxon (fix): | Mammaliaformes |

Living members of the clade include the monotremes (Monotremata), marsupials (Marsupialia) and the eutherians (Placentalia).[2][3]

Mammaliforms have highly specialized molar teeth, with cusps and flat regions for grinding food. This is a single inherited system in present mammals, but it seems to have evolved convergently in pre-mammals more than once.[4] Instead of having many teeth that are frequently replaced, mammals have one set of baby teeth and later one set of adult teeth which fit together precisely. This may help to grind food, and make it easier to digest.

Lactation (milk) and fur, along with other features, also characterize the Mammaliaformes, though these traits are difficult to study in the fossil record. The fossilized remains of Castorocauda lutrasimilis are an exception to this.

Evolution of early mammals

Fossils of Mesozoic proto-mammals are scarce. There were only 116 in 1979, but this has changed in recent times. There were about 310 in 2007, with an increase in quality: there are "at least 18 Mesozoic mammals [with] nearly complete skeletons".[5]

Ecological niches in the Mesozoic

There is still some truth in the "small, nocturnal insectivores" stereotype, but recent finds show that proto-mammals gradually developed a variety of lifestyles. For example:

- Castorocauda, a member of Docodonta lived in the Middle Jurassic about 164 million years ago (mya). It was about 42.5 cm (16.7 in) long, weighed 500–800 g (18–28 oz), had limbs that were adapted for swimming and digging and teeth adapted for eating fish.[6] Another docodont, Haldanodon, also had semi-aquatic habits. Aquatic tendencies were probably common among docodonts, since they lived in wetland environments.[7]

- Multituberculates are allotherians that survived for over 125 mya (from mid-Jurassic, about 160 mya, to late Eocene, about 35 mya) are often called the "rodents of the Mesozoic". They may have given birth to tiny live neonates rather than laying eggs.

- Fruitafossor, from the Upper Jurassic about 150 mya, was about the size of a chipmunk. Its teeth, forelimbs and back suggest that it broke open the nest of social insects to prey on them (probably termites.[8]

- Spinolestes also had adaptations for digging, so it also might have had anteater-like habits. It is notable for quills like those of modern spiny mice.

- Volaticotherium is from the boundary with the Lower Cretaceous about 125 mya. It is the earliest-known gliding mammal and had a gliding membrane that stretched out between its limbs, rather like a modern flying squirrel. This suggests it was active mainly during the day.[9] It is not the only example of this type of locomotion.

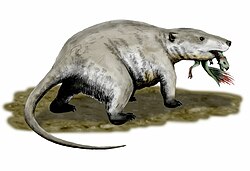

- Repenomamus, from the early Cretaceous 130 mya, was a stocky, badger-like predator that sometimes preyed on young dinosaurs. Two species have been recognized, the largest over a metre long.[10][11]

- Ichthyoconodon is known from mollariforms found in marine deposits. These teeth are sharp-cusped and similar in shape to those of piscivorous mammals. This has been taken to mean that it was a marine mammal, one of the few examples known from the Mesozoic.[12]

This paints a picture of small-sized mammals being already quite successful and diversified in the Jurassic and early Cretaceous.

Taxonomy

In some sources Class Mammalia takes the place of Mammaliaformes, and includes all members of that clade.

- MAMMALIAFORMES

References

- ↑ Rowe T.S. 1988. Definition, diagnosis, and origin of Mammalia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 8 (3): 241–264. doi:10.1080/02724634.1988.10011708.

- ↑ Kielan-Jaworowska, Zofia; Cifelli, Richard L. and Luo, Zhe-Xi 2004. Mammals from the age of dinosaurs. Columbia N.Y. ISBN 0-231-11918-6

- ↑ Kemp T.S. 2005. The origin & evolution of mammals. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Hunter J.P. & Jernvall J. 1995. The hypocone as a key innovation in mammalian evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 (23): 10718–22. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.23.10718. PMC 40683. PMID 7479871.

- ↑ Luo Z.-X. (2007). "Transformation and diversification in early mammal evolution" (PDF). Nature. 450 (7172): 1011–1019. Bibcode:2007Natur.450.1011L. doi:10.1038/nature06277. PMID 18075580. S2CID 4317817. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-24. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

- ↑ Ji Q.; Luo Z-X, Yuan C-X, and Tabrum A.R. 2006. A swimming mammaliaform from the Middle Jurassic and ecomorphological diversification of early mammals. Science 311 (5764): 1123–7. [1]

- ↑ Paleontology and geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: Bulletin 36

- ↑ Luo Z.-X. & Wible J.R. (2005). "A late Jurassic digging mammal and early mammal diversification". Science. 308 (5718): 103–107. Bibcode:2005Sci...308..103L. doi:10.1126/science.1108875. PMID 15802602. S2CID 7031381.

- ↑ Meng J.; et al. (2006). "A Mesozoic gliding mammal from northeastern China". Nature. 444 (7121): 889–893. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..889M. doi:10.1038/nature05234. PMID 17167478. S2CID 28414039.

- ↑ Li J.; et al. (2000). "A new family of primitive mammal from the Mesozoic of western Liaoning, China". Chinese Science Bulletin. 46 (9): 782–785. doi:10.1007/BF03187223. S2CID 129025369. abstract, in English Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hu Y.; et al. (2005). "Large Mesozoic mammals fed on young dinosaurs" (PDF). Nature. 433 (7022): 149–152. Bibcode:2005Natur.433..149H. doi:10.1038/nature03102. PMID 15650737. S2CID 2306428.[dead link]

- ↑ Sigogneau-Russell D. 1995. Two possibly aquatic triconodont mammals from the early Cretaceous of Morocco. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 40(2), p.149-162.

| Wikispecies has information on: Mammaliaformes. |