Pythagorean theorem

In mathematics, the Pythagorean theorem or Pythagoras's theorem[dead link] is a statement about the sides of a right triangle.

One of the angles of a right triangle is always equal to 90 degrees. This angle is the right angle. The two sides next to the right angle are called the legs and the other side is called the hypotenuse. The hypotenuse is the side opposite to the right angle, and it is always the longest side.

Claim of the theory

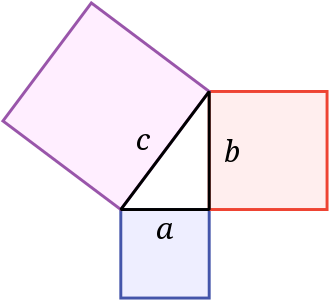

The Pythagorean theorem says that the area of a square on the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares on the legs. In this picture, the area of the blue square added to the area of the red square makes the area of the purple square. It was named after the Greek mathematician Pythagoras:

If the lengths of the legs are a and b, and the length of the hypotenuse is c, then, [math]\displaystyle{ a^2+b^2=c^2 }[/math].

Types of proofs

There are many different proofs of this theorem. They fall into four categories:

- Those based on linear relations: the algebraic proofs.

- Those based upon comparison of areas: the geometric proofs.

- Those based upon the vector operation.

- Those based on mass and velocity: the dynamic proofs.[1]

Proof

One proof of the Pythagorean theorem was found by a Greek mathematician, Eudoxus of Cnidus.

The proof uses three lemmas:

- Triangles with the same base and height have the same area.

- A triangle which has the same base and height as a side of a square has the same area as a half of the square.

- Triangles with two congruent sides and one congruent angle are congruent and have the same area.

The proof is:

- The blue triangle has the same area as the green triangle, because it has the same base and height (lemma 1).

- Green and red triangles both have two sides equal to sides of the same squares, and an angle equal to a straight angle (an angle of 90 degrees) plus an angle of a triangle, so they are congruent and have the same area (lemma 3).

- Red and yellow triangles' areas are equal because they have the same heights and bases (lemma 1).

- Blue triangle's area equals area of yellow triangle's area, because

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\color{blue}A_{blue}}={\color{green}A_{green}}={\color{red}A_{red}}={\color{yellow}A_{yellow}} }[/math]

- The brown triangles have the same area for the same reasons.

- Blue and brown each have a half of the area of a smaller square. The sum of their areas equals half of the area of the bigger square. Because of this, halves of the areas of small squares are the same as a half of the area of the bigger square, so their area is the same as the area of the bigger square.

Proof using similar triangles

We can get another proof of the Pythagorean theorem by using similar triangles.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{d}{a} = \frac{a}{c} \quad \Rightarrow \quad {a^2} = {dc}\quad (1) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{e}{b} = \frac{b}{c} \quad \Rightarrow \quad {b^2} = {ec}\quad (2) }[/math]

From the image, add equations (1) and (2):

- [math]\displaystyle{ {a^2} + {b^2} = {dc + ec} \quad \Rightarrow a^2 + b^2 = c (d + e) \quad \Rightarrow a^2 + b^2 = c(c) }[/math]

And we get:

- [math]\displaystyle{ c^2 = a^2 + b^2 \,\!. }[/math]

Pythagorean triples

Pythagorean triples or triplets are three whole numbers which fit the equation [math]\displaystyle{ a^2+b^2=c^2 }[/math].

The triangle with sides of 3, 4, and 5 is a well known example. If a=3 and b=4, then [math]\displaystyle{ 3^2+4^2=5^2 }[/math] because [math]\displaystyle{ 9+16=25 }[/math]. This can also be shown as [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{3^2+4^2}=5. }[/math]

The three-four-five triangle works for all multiples of 3, 4, and 5. In other words, numbers such as 6, 8, 10 or 30, 40 and 50 are also Pythagorean triples. Another example of a triple is the 12-5-13 triangle, because [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{12^2+5^2}=13 }[/math].

A Pythagorean triple that is not a multiple of other triples is called a primitive Pythagorean triple. Any primitive Pythagorean triple can be found using the expression [math]\displaystyle{ (2mn,m^2-n^2,m^2+n^2) }[/math], but the following conditions must be satisfied. They place restrictions on the values of [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] are positive whole numbers

- [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] have no common factors except 1

- [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] have opposite parity. [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] have opposite parity when [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] is even and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] is odd, or [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] is odd and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] is even.

- [math]\displaystyle{ m\gt n }[/math].

If all four conditions are satisfied, then the values of [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] create a primitive Pythagorean triple.

[math]\displaystyle{ m=2 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math] create a primitive Pythagorean triple. The values satisfy all four conditions. [math]\displaystyle{ 2mn=2\times2\times1=4 }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ m^2-n^2=2^2-1^2=4-1=3 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ m^2+n^2=2^2+1^2=4+1=5 }[/math], so the triple [math]\displaystyle{ (3,4,5) }[/math] is created.

Pythagorean Theorem Media

Rearrangement proof of the Pythagorean theorem.(The area of the white space remains constant throughout the translation rearrangement of the triangles. At all moments in time, the area is always c2. And likewise, at all moments in time, the area is always a2 + b2.)

- Einstein-trigonometric-proof.svg

Right triangle on the hypotenuse dissected into two similar right triangles on the legs, according to Einstein's proof.

- Illustration to Euclid's proof of the Pythagorean theorem.svg

Proof in Euclid's Elements

- Illustration to Euclid's proof of the Pythagorean theorem2.svg

Illustration including the new lines

- Illustration to Euclid's proof of the Pythagorean theorem3.svg

Showing the two congruent triangles of half the area of rectangle BDLK and square BAGF

- Pythag anim.gif

Animation showing proof by rearrangement of four identical right triangles

- Pythagoras-2a.gif

Animation showing another proof by rearrangement

- Pythagorean theorem rearrangement.svg

Proof using an elaborate rearrangement

References

- ↑ Loomis, Elisha S. 1927. The Pythagorean proposition: its proofs analysed and classified and bibliography of sources. Cleveland, Ohio.