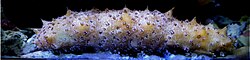

Sea cucumber

Sea cucumbers are a class of echinoderms, the Holothuroidea. They have a longish body, and leathery skin. Sea cucumbers live on the floor of the ocean. Most sea cucumbers are scavengers. There are about 1500 species of sea cucumbers. Sea cucumbers have a unique respiratory system, and effective defences against predators. The Chinese people eat them.

| Sea Cucumber | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | Holothuroidea

|

Like all echinoderms, sea cucumbers have an endoskeleton just below the skin, calcareous structures that are usually reduced to isolated ossicles joined by connective tissue. These can sometimes be enlarged to flattened plates, forming an armour. In pelagic species the skeleton is absent.[1][2]

Overview

Sea cucumbers communicate with each other by sending hormone signals through the water.

A remarkable feature of these animals is the collagen which forms their body wall. This can be loosened and tightened at will. If the animal wants to squeeze through a small gap, it can undo the collagen connections, and pour into the space. To keep itself safe in these cracks, the sea cucumber hooks up all its collagen fibres to make its body firm again.[3]

The animals have an internal respiratory tree which floats in the internal watery cavity. At the rear, water is pumped in and out of the cloaca,[4] so gaseous exchange takes place with the resiratory tree in the gut.[5]p80

Defense

Some species of coral reef sea cucumbers defend themselves by expelling sticky cuvierian tubules to entangle potential predators. These tubules are attached to the respiratory tree in the gut. When startled, these cucumbers may expel the tubules through a tear in the wall of the cloaca. In effect, this squirts sticky threads all over a predator. Replacement tubules grow back in one-and-a-half to five weeks, depending on the species.[6] The release of these tubules can also be accompanied by the discharge of a toxic chemical known as holothurin, which has similar properties to soap. This chemical can kill any animal in the vicinity and is one more way in which these sedentary animals can defend themselves.[3] Other cucumbers, lacking this device, can split their intestinal wall, and spew out their gut and respiratory tree. They regenerate them later. Zoologists who experience this believe it to be an impressive deterrent. "The mess one individual can make must be seen to be believed".[5]p81

The existence of these defences explains why the holothurians were able to do without the strong skeleton of their ancestors.

Feeding

Highly modified tube feet around the mouth are always present. These are branched and retractile tentacles, much larger than the regular tube feet. Sea cucumbers have between ten and thirty such tentacles, depending on the species. There is a ring of larger ossicles round the mouth and oesophagus to which the muscles of the tube feet are attached.[7] With their sticky tentacles the animal collects detritus and small organisms.

References

- ↑ Pelagic sea cucumber: Information from Answers.com

- ↑ Reich, Mike (2006). Lefebvre B. David B. Nardin E. & Poty E. (ed.). "Cambrian holothurians ? – The early fossil record and evolution of Holothuroidea" (PDF). Journées Georges Ubaghs. Dijon, France: Université de Bourgogne: 36–37.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Piper, Ross (2007). Extraordinary animals: an encyclopedia of curious and unusual animals. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313339228.

- ↑ A cloaca is a joint anus and sexual opening

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Nichols D. 1962. Echinoderms. Hutchinson, London. ISBN 0-09-065994-5

- ↑ Flammang, Patrick (2002-12-01). "Biomechanics of adhesion in sea cucumber cuvierian tubules (echinodermata, holothuroidea)". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 42 (6): 1107–1115. doi:10.1093/icb/42.6.1107. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders. pp. 981–997. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.