Witch

A witch is a person, who practices witchcraft or magic. Traditionally, the word was used to accuse someone of bewitching someone, or casting a spell on them to gain control over them by magic. It is now also used by some to refer to those who practice various wise crafts such as Hedge witch Witches usually used spells for personal gain.

History

Although most indigenous peoples throughout history have had some beliefs about spirits and people believed to have power through herbs or spirits, these were not called 'witches' until contact with western ideas. Neither did they always have negative connotations.

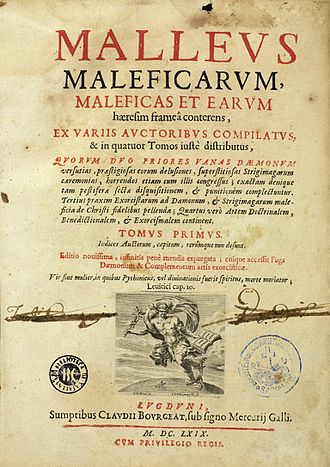

In Europe, the panic over witchcraft was supported by the Malleus Maleficarum, published in 1487 by Heinrich Kramer, a German Catholic clergyman. It taught the prosecution of witches and was greatly promoted by the new technology of the printing press. It saw 29 printings before 1669, second only to the Bible. The book says that three elements are necessary for witchcraft. These are the evil intentions of the witch, the help of the Devil, and the permission of God.[1]

Many women in South America and throughout Europe were killed by witch hunts. The exact number is hotly debated because of a lack of record keeping and different opinions on the time frames and regions that ought to be included. Since the entire persecuting legal system, "judges, ministers, priests, constables, jailers, judges, doctors, prickers, torturers, jurors, executioners" were nearly all male and the victims were overwhelmingly female, the witch hunts are considered by many to be a "gynocide". In the documentary The Burning Times, Thea Jensen calls this period in history a "Women's Holocaust".

Modern understanding

In the 20th century, a new attempt has been made at understanding witchcraft. Many people say that witches were in fact wise women who were hunted down by the church (mostly for their knowledge of herbs to treat certain diseases). This has led to a new movement. Some of it is known as Wicca.

Heather Marsh has tied the persecution of witches to the fight of church and industry to control "the power of life and death" at a time when industry needed more workers. She also argues the persecution of witches was a fight for centralized power over the peasant rebellions and the ownership of knowledge by medicine and science which forbade the earlier teaching or practices by women and indigenous cultures. She writes that the persecution of witches has colored misogyny since the 1400s.[2]

Silvia Federici tied the witch hunts to a history of the female body in the transition to capitalism.[3]

Witchcraft and accusations of witchcraft are still very common in some parts of West Africa.

Witch crimes in the Malleus Maleficarum

Control of procreation was a constant theme, as was medical knowledge:

Concerning Witches who copulate with Devils. Why is it that Women are chiefly addicted to Evil superstitions?

Whether Witches may work some Prestidigatory Illusion so that the Male Organ appears to be entirely removed and separate from the Body.

That Witches who are Midwives in Various Ways Kill the Child Conceived in the Womb, and Procure an Abortion; or if they do not this Offer New-born Children to Devils.

How Witches Impede and Prevent the Power of Procreation.

How, as it were, they Deprive Man of his Virile Member.

Of the Manner whereby they Change Men into the Shapes of Beasts.

Of the Method by which Devils through the Operations of Witches sometimes actually possess men.

Of the Method by which they can Inflict Every Sort of Infirmity, generally Ills of the Graver Kind.

Of the Way how in Particular they Afflict Men with Other Like Infirmities.

How Witch Midwives commit most Horrid Crimes when they either Kill Children or Offer them to Devils in most Accursed Wise.

Film

Famous people accused of witchcraft

- The witches of Salem, Massachusetts. The trials of 1692 contributed to the title of "the Witch-city", Salem has today.

- Elizabeth of Doberschütz, beheaded and burnt outside the gates of Stettin, on 17 December 1591.[4][5]

- Anna Roleffes, better known as Tempel Anneke was one of the last witches to be executed in Braunschweig. She was executed 30 December 1663.[6]

- The Samlesbury witches, tried in one of the most famous witch trials in English history. They were found not guilty, but ten other people were found guilty and hanged.

- Hester Jonas, known as The Witch of Neuss. Beheaded and burnt on Christmas Eve 1635. She was about 64 years old. The complete proceedings of the trial is still available in Neuss.

- Catherine Monvoisin, close to Marquise the Montespan, a lover of Louis XIV. She delivered poisons, and held black masses, against payment. Burnt with some others on the Place de la Grève in Paris, in 1680.

- Maria Holl, also known as The Witch of Nördlingen. She was one of the first women to withstand being tortured during her Witch-trial of 1593/1594. It was through her force that she rid the town of Nördlingen of the Witch-craze. Her act led to doubts quelling up about the righteousness of witch-trials. She was cleared of the accusations. She died in 1634, probably from the plague.

- Anna Schnidenwind, one of the last women to be publicly executed for Witchcraft in Germany. Burnt after being strangled, in Endingen am Kaiserstuhl, 24 April 1751.[7]

- Anna Göldi (or Göldin). Last witch to be executed in Europe. This happened in Glarus, Switzerland, in the summer of 1782.

- Joan of Arc, accused of witchcraft and was burned.

References

- ↑ Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1972). Witchcraft in the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-8014-9289-1.

- ↑ Marsh, Heather. "Witches and how they are silenced".

- ↑ Silvia Federici 2004. Caliban and the Witch: women, the body and primitive accumulation.

- ↑ Wehrmann, Martin (1979). Geschichte der Stadt Stettin. Weidlich. p. 264. ISBN 978-3-8128-0033-4.

- ↑ Branig, Hans; Buchholz, Werner (1997). Geschichte Pommerns. Böhlau. p. 158. ISBN 978-3-412-07189-9.

- ↑ Morton, Peter, ed. (2006). The Trial of Tempel Anneke: Records of a Witchcraft Trial in Brunswick, Germany. Barbara Dähms, translator. Ontario: University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Klaus Graf: Der Endinger Hexenprozess gegen Anna Trutt von 1751 (2012) online.

Other websites

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- Some historical notes on the witch-craze from historian Trevor Roper

- Kabbalah On Witchcraft - A Jewish view (Audio) chabad.org

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Witchcraft

- Witchcraft in the Catholic Encyclopedia on (New Advent)

- Witchcraft and Devil Lore in the Channel Islands, 1886, by John Linwood Pitts, from Project Gutenberg

- A Treatise of Witchcraft, 1616, by Alexander Roberts, from Project Gutenberg

- The Witches' Voice 1997-2007 The Witches' Voice Inc