Classical Chinese

Classical Chinese or literary Chinese is a traditional register of written Chinese. It is based on the grammar and vocabulary of ancient Chinese, so it is very different from any modern spoken form of Chinese. Classical Chinese was once used for almost all formal writing before and during the beginning of the 20th century in China, and during various different periods in Korea, Japan and Vietnam. Among Chinese speakers, Classical Chinese has been largely replaced by written vernacular Chinese, or 白话/白話 báihuà ("plain speech") after the overthrow of the Qing dynasty and therefore the end of Imperial China. Written Vernacular Chinese is a writing style very closely related to modern spoken Mandarin Chinese. At the same time, non-Chinese speakers have largely given up Classical Chinese, and use their local languages or dialects instead.

| Classical Chinese | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literary Chinese 古文 or 文言 | ||||

| Region | China, Ryukyu, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam | |||

| Era | 5th century BC to 2nd century AD; continued as a literary language until the 20th century | |||

| Language family | Sino-Tibetan

| |||

| Writing system | Chinese | |||

| Language codes | ||||

| ISO 639-3 | lzh | |||

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-aa | |||

| ||||

| Classical Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 文言文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "literary language writing" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Although many words and phrases used in Classical Chinese have been replaced by words and phrases made up of different characters in Standard Chinese, many of the characters that were common in Classical Chinese can be found in modern Chinese words and phrases as well as retain their meanings. For example, while the word "to eat" is 食 (shí) in Classical Chinese, it is 吃 (chī) in Standard Chinese. However, the character 食 is still found in words related to food and eating like 食品 (shípĭn), which is the Standard Chinese word for "food". The chart below compares Classical Chinese words to the Standard Chinese words that replaced them.

| English word/phrase | Classical Chinese word (pinyin) | Standard Chinese word (pinyin) |

|---|---|---|

| "to not have/to lack" | 无/無 (wú) | 没有 (měiyóu) |

| "to say" | 曰 (yuē) | 说/說 (shuō) |

| "teacher" | 先生 (xiānshēng) | 老师/老師 (lǎoshī) |

| "eye" | 目 (mù) | 眼睛 (yănjing) |

| "to drink" | 饮/飮 (yĭn) | 喝 (hē) |

Many modern Chinese words and phrases either came from northern dialects or are loanwords from other languages such as Mongolian or Korean.

Due to the changes of the spoken Chinese over the centuries, spoken Chinese lost many sounds that existed in older dialects, and therefore many words in Classical Chinese were beginning to sound too much like each other. Although documents written in Classical Chinese can be reasonably understood by someone who can read Chinese, they can be very difficult to understand when they are read aloud.[1] One-syllable articles, or poems written in Classical Chinese in which every word in the poem is pronounced by the same syllable, are perfect examples that how impractical Classic is as a spoken language. The title of one poem 施氏食狮史 (Shī Shì Shí Shī Shǐ), known as the "Lion-Eating Poet of the Stone Den" in English, literally translates to "The Story of Shi Shi Eating Lions". Every single word of the poem is pronounced "shi", even though they have different tones.[2] If the title were to be translated into Standard Chinese, it be read something like 施氏吃狮子的史诗 (Shī Shì chī shīzi de shǐshī).

Structurally, words in Classical Chinese tend to be much simpler because they are usually made up of one Chinese character, while in Standard Chinese most words are made of two to four characters. This is so that the writer can write what they want to write using as few characters as possible. Examples are found below.

| English word/phrase | Classical Chinese word (pinyin) | Homophone to Classical Chinese word (meaning) | Standard Chinese word (pinyin) |

|---|---|---|---|

| chopstick(s) | 筷 (kuài) (Old Chinese 箸[3]) | 快 (fast/quick) | 筷子 (kuàizi) |

| lion(s) | 狮/獅 (shī) | 诗/詩 (poem) | 狮子/獅子 (shīzi) |

| history/annals | 史 (shĭ) | 始 (begin/start) | 历史/歷史 (lìshĭ) |

| friend(s) | 朋 (péng) | 硼 (boron) | 朋友 (péngyǒu) |

| education | 教 (jiào) | 酵 (ferment/leaven) | 教育 (jiàoyù) |

Once again, due to the merging of Chinese sounds, extra characters are added to words in Standard Chinese to distinguish similar-sounding words that would otherwise be impossible to tell apart.

Examples of phrases in Classical Chinese is Confucius's famous quote 有教無類 (yǒu jiào wú lèi), which roughly translates to, "In education, there should be no class distinction."

Classical Chinese Media

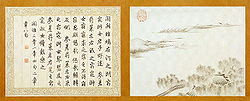

The Classic of Poetry, a collection of 305 literary works authored between the 11th and 7th centuries BCE in what is generally termed "pre-Classical Chinese"

A Literary Chinese letter written in 1266, addressed to the "King of Japan" (日本國王) on behalf of Kublai Khan, prior to the Mongol invasions of Japan. Annotations explaining points of grammar have been added to the text, intended to aid Japanese-speaking readers.

References

- ↑ "How to Read a Chinese Poem with Only One Sound". Chinese Pod.

- ↑ ""Lion-Eating Poet" Tongue-Twister Essay". YellowBridge.com.

- ↑ "筷子". wikitionary. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

| This language has its own Wikipedia project. See the Classical Chinese edition. |