El Niño–Southern Oscillation

El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO in short) is a term for a natural event that takes place in the Pacific Ocean. It is also called El Niño and La Niña. In Spanish they mean "The boy" and "The girl".

El Niño happens when the sea water temperature rises in surface waters of the tropical Pacific Ocean. Every two to five years the Pacific Ocean has this event. A weak, warm current starts around Christmas along the coast of Ecuador and Peru. It lasts for only a few weeks to a month or more. Every three to seven years, an El Niño event may last for many months. This can change the weather and have important effects around the world. Australia and Southeast Asia can have drought but the deserts of Peru have very heavy rainfall. East Africa can have both. In a La Niña event the weather patterns are reversed.

The Southern Oscillation was discovered by Sir Gilbert Walker in 1923.[1] It is a "seesaw" of atmospheric pressure between the Pacific and Indian Oceans. There is an inverse relationship between the air pressure measured at two sites: Darwin, Australia, in the Indian Ocean and the island of Tahiti in the South Pacific. The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) is the difference in sea-level pressure measured at Tahiti and Darwin. The Cold Tongue (CT) Index measures how much the average sea-surface temperature in the central and eastern Pacific near the equator varies from the annual cycle. The two measurements are anti-correlated, so that a negative SOI is usually together with an unusual warm ocean wind known as El Niño.

By the early 1980s it was clear that El Niño and the Southern Oscillation were related, and the acronym ENSO is used to describe this large-scale event.

The 2010-2011 Queensland floods were caused by a La Niña event which brought very heavy rain to the east coast of Australia. Other big floods in Australia have also happened during a La Niña, 1916, 1917, 1950, 1954-1956, and 1973-1975.[2] The cost of the 2010-2011 Queensland floods has been worked out to A$30 billion.[3]

Central Pacific El Niño

Not all El Niños happen in the Eastern Pacific. During recent decades, Central Pacific El Niños have been discovered. When these happen, the effects from CP El Niños are very different from traditional El Niños. Central Pacific El Niños took place in 1986–88, 1991–92, 1994–95, 2002–03, 2004–05, 2006–07, 2009–10 and 2015–16.[4][5]

El Niño–Southern Oscillation Media

- Soi.svg

Southern Oscillation Index timeseries 1876–2017.

- Soi-map.png

Southern Oscillation Index correlated with mean sea level pressure.

- LaNina.png

Diagram of the quasi-equilibrium and La Niña phase of the Southern Oscillation. The Walker circulation is seen at the surface as easterly trade winds which move water and air warmed by the sun towards the west.

- NinoRegions.png

The various "Niño regions" where sea surface temperatures are monitored to determine the current ENSO phase (warm or cold)

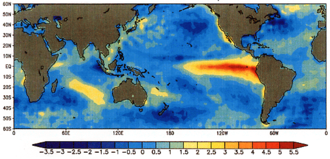

- Mean sst equatorial pacific.gif

Average equatorial Pacific temperatures

- 1997 El Nino TOPEX.jpg

The 1997 El Niño observed by TOPEX/Poseidon

- Fig4a ENSOindices Nino3.4only large.png

The regions where the air pressure are measured and compared to generate the Southern Oscillation Index

- MJO 5-day running mean through 1 Oct 2006.png

A Hovmöller diagram of the 5-day running mean of outgoing longwave radiation showing the MJO. Time increases from top to bottom in the figure, so contours that are oriented from upper-left to lower-right represent movement from west to east.

- 20210827 Global surface temperature bar chart - bars color-coded by El Niño and La Niña intensity.svg

Colored bars show how El Niño years (red, regional warming) and La Niña years (blue, regional cooling) relate to overall global warming. The El Niño–Southern Oscillation has been linked to variability in longer-term global average temperature increase.

References

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Utilities at line 38: bad argument #1 to 'ipairs' (table expected, got nil).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Utilities at line 38: bad argument #1 to 'ipairs' (table expected, got nil).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Utilities at line 38: bad argument #1 to 'ipairs' (table expected, got nil).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Utilities at line 38: bad argument #1 to 'ipairs' (table expected, got nil).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Utilities at line 38: bad argument #1 to 'ipairs' (table expected, got nil).