Epicurus

Epicurus[2] (Samos, 341 BC – Athens, 270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher. He started a school of philosophy called Epicureanism.

Epicurus | |

|---|---|

Roman marble bust of Epicurus | |

| Born | February 341 BC |

| Died | 270 BC |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Epicureanism, atomism, materialism, hedonism |

Main interests | Physics, ethics, epistemology |

Notable ideas | Pleasure principle, the "moving"/"static" pleasures distinction, ataraxia, aponia, atomic swerve[1] |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

Life

As a boy he studied philosophy under the Platonist teacher Pamphilus for about four years. At the age of 18 he went to Athens for his two-year term of military service. Epicurus never married and had no children, so far as we know.

Teachings

Epicurus helped in the development of science and the scientific method because he said that nothing should be believed except what we can test through direct observation and logical deduction. His ideas about nature and physics hinted at scientific concepts developed in modern times.

Works

Epicurus' only surviving complete works are three letters, which can be found in book X of Diogenes Laertius' Lives of Eminent Philosophers, and two groups of quotes: the Principal Doctrines, reported as well in Diogenes' book X, and the Vatican Sayings, preserved in a manuscript from the Vatican Library.

Many pieces of his thirty-seven volume treatise On Nature have been found in the burnt papyrus fragments at the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum.

Epicurus Media

Herm of Epicurus (left) leaning against his disciple Metrodorus in the Louvre Museum

Reconstruction by K. Fittschen of an Epicurus enthroned statue, presumably set up after his death. University of Göttingen, Abgußsammlung

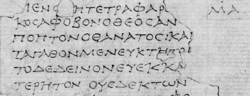

An illustration of an unrolled papyrus recovered from the Epicurean Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum

Bronze bust of Epicurus recovered from the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, which contains a library of Epicurean works collected by Philodemus.

Diogenes of Oenoanda, an Epicurean philosopher living in Lycia, in the early 2nd century AD, inscribed roughly 260 square meters of Epicurean writings onto the portico walls of his own residence, which were rediscovered in the 1880s.

Epicurus in Raphael's School of Athens (1509–1511). In the Middle ages, Epicurus was depicted in popular culture as a vain pleasure-seeker.

References

Further reading

- Bailey C. (1928) The Greek Atomists and Epicurus, Oxford.

- Bakalis Nikolaos (2005) Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics Analysis and Fragments, Trafford Publishing, ISBN 1-4120-4843-5

- Digireads.com The Works of Epicurus, January 2004.

- Eugene O’ Connor The Essential Epicurus, Prometheus Books, New York 1993.

- Edelstein Epicureanism, Two Collections of Fragments and Studies Garland Publ. March 1987

- Farrington, Benjamin. Science and Politics in the Ancient World, 2nd ed. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1965. A Marxist interpretation of Epicurus, the Epicurean movement, and its opponents.

- Gottlieb, Anthony. The Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance. London: Penguin, 2001. ISBN 0-14-025274-6

- Inwood, Brad, tr. The Epicurus Reader, Hackett Publishing Co, March 1994.

- Oates Whitney Jenning, The Stoic and Epicurean philosophers, The Complete Extant Writings of Epicurus, Epictetus, Lucretius and Marcus Aurelius, Random House, 9th printing 1940.

- Panicha, George A. Epicurus, Twayne Publishers, 1967

- Prometheus Books, Epicurus Fragments, August 1992.

- Russel M. Geer Letters, Principal Doctrines, Vatican Sayings, Bobbs-Merrill Co, January 1964.

- Diogenes of Oinoanda. The Epicurean Inscription, edited with Introduction, Translation and Notes by Martin Ferguson Smith, Bibliopolis, Naples 1993.

Other websites

- Epicurus.info Archived 2016-01-26 at the Wayback Machine – Epicurean Philosophy Online: features classical e-texts & photos of Epicurean artifacts.

- Epicurus.net Archived 2019-08-16 at the Wayback Machine – Epicurus and Epicurean Philosophy

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Entry for "Epicurus"

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Entry for "Epicurus"

- Epicurus & Lucretius – Small article by "P. Dionysius Mus"

- The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature – Karl Marx’s doctoral thesis.

- "Epicurus on Happiness" Archived 2007-12-15 at the Wayback Machine – A documentary about the philosophy of Epicurus.

- Principal Doctrines Archived 2007-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Vatican Sayings Archived 2019-03-21 at the Wayback Machine

- The Garden of Epicurus – useful summary of the teachings of Epicurus

- Letters

- Letter to Herodotus Archived 2018-10-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Letter to Pythocles Archived 2018-10-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Letter to Menoeceus Archived 2017-01-03 at the Wayback Machine