Geostationary orbit

A geostationary orbit (or Geostationary Earth Orbit - GEO) is a type of geosynchronous orbit directly above the Earth's equator (0° latitude). Like all geosynchronous orbits, it has a period (time for one orbit) that is 24 hours. This means it goes around the Earth as fast as the Earth spins, and so it appears to stay above the same spot all the time. A person watching from Earth sees a satellite in a geostationary orbit as not moving, at a steady place in the sky.

Satellites in geostationary orbit

Communications satellites and weather satellites often use these orbits, so that the satellite antennas that communicate with them do not have to move to track them. The ground atennas can be pointed permanently at a fixed position in the sky. This is cheaper and easier than having a satellite dish that is always moving to track a satellite. Each one stays above the equator at a set longitude (distance east or west).

The idea of a geosynchronous satellite for communication was first published in 1928 (but not widely so) by Herman Potočnik.[1] The idea of a geostationary orbit became well known first in a 1945 paper called "Extra-Terrestrial Relays — Can Rocket Stations Give Worldwide Radio Coverage?" by the British science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, published in Wireless World magazine. The orbit, which Clarke first described as good for broadcast and relay communications satellites,[2] is sometimes called the Clarke Orbit.[3] Named after the author, the Clarke Belt is this part of space above the Earth - about 35,786 km (22,000 mi) above sea level, over the equator, where near-geostationary orbits may be implemented. The Clarke Orbit (another name for a geostationary orbit) is about 265,000 km (165,000 mi) around.

Details of the orbit

The satellite orbits in the direction of the Earth's rotation, producing an orbital period equal to the Earth's period of rotation, known as the sidereal day (very nearly 24 hours).

The orbit needs to be above the equator. Since all orbits are around the center of the Earth, if it was tipped above the equator (so that the satellite was straight above New York City, for example) it would need to swing an equal distance to the south pole on each orbit. It needs to spend an equal amount of time on each side of the equator. So if it is directly above the equator, it doesn't move north or south at all. (Geosynchronous orbits are like geostationary orbits, but also include those that go above and below the equator).

The height of the orbit is an exact distance, because the speed of the orbit depends on how far it is from the center of the Earth. An orbit is a balance between centripetal force against the Earth's gravity. Objects closer to Earth feel more gravity. This is why objects in low orbit (like the International Space Station orbit the Earth very quickly, about 90 minutes or so for each orbit. Objects farther away take longer for each orbit. The moon for instance, takes about 29 days for each orbit.

Because this orbit is so high, it takes radio (and light) waves about 1/4 second to go up to the satellite and back to Earth. This means that a broadcast interview taking place between the television station and a distant reporter can have a gap of a half second (1/4 second to go from the studio to the reporter, and a 1/4 second back to the studio, where the signal is then sent to viewer). This half second delay can be noticed in many news broadcasts.

When satellites reach the end of their life, it would be too expensive to bring them all the way back down to Earth to burn up in the atmosphere. It is much cheaper to put them a little higher (300 km) in a 'graveyard' orbit, where they will stay essentially forever.[4]

Geostationary Orbit Media

A 5° × 6° view of a part of the geostationary belt, showing several geostationary satellites. Those with inclination 0° form a diagonal belt across the image; a few objects with small inclinations to the Equator are visible above this line. The satellites are pinpoint, while stars have created star trails due to Earth's rotation.

Syncom 2, the first geosynchronous satellite

Service areas of satellite-based augmentation systems (SBAS).

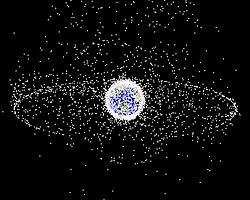

A computer-generated image from 2005 showing the distribution of mostly space debris in geocentric orbit with two areas of concentration: geostationary orbit and low Earth orbit.

References

- ↑ Noordung, Hermann; et al. (1995) [1929]. The Problem With Space Travel. Translation from original German. DIANE Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 978-0788118494.

- ↑ "Extra-Terrestrial Relays — Can Rocket Stations Give Worldwide Radio Coverage?" (PDF). Arthur C. Clark. October 1945. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ "Basics of Space Flight Section 1 Part 5, Geostationary Orbits". NASA. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ "NASA end-of-life practices for satellites" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

Other websites

- Graphical derivation of the geostationary orbit radius for the Earth Archived 2008-11-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Orbital Mechanics (Rocket and Space Technology)

- List of satellites in geostationary orbit

- Clarke Belt Snapshot Calculator Archived 2006-06-26 at the Wayback Machine

- 3D Real Time Satellite Tracking Archived 2005-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Geostationary satellite orbit overview Archived 2014-04-04 at the Wayback Machine