God paradox

The God paradox is an idea in philosophy. This idea is explained here:

- If God is able to do anything, may this mean He is able to make a mountain heavier than He is able to lift?

This is a paradox because:

- If God is able to make a mountain heavier than He is able to lift, then there may be something He is not able to do: He is not able to lift that mountain. Yes and no

- If God is not able to make such a mountain, then there is something He is not able to do: He is not able to make that mountain.

If either outcome were considered true, then it is argued that God Almighty is actually not almighty.

Answers to the God Paradox

The God paradox is a good example of a philosophical problem. This section has some answers to this paradox.

One answer is that God could make it so he can't lift the mountain by his own choice. In other words, God can lift the unliftable mountain because he is all powerful, but he chooses not to be able to, and so he chooses to cut his own power, because he is able. God can also choose to not be able to create such a mountain. God is all powerful, so he can choose not to have the power to make an unliftable mountain. Simply said, God can cut his own power, but in so doing, he can still regain that power. It is a limbo, a state between not powerful and powerful, something that is not definable by our knowledge of what is possible or impossible. Because God is almighty, he surpasses our definitions of what he can and cannot do.

God cannot

This answer says God is able to do only things less than God. If you say there exists a mountain that is "heavier than anybody is able to lift," then what you say is funny: it means nothing, because God is able to lift any mountain. This is because saying a mountain is "too heavy to lift" means this mountain cannot be lifted by anybody. This does not mean that God is too weak to lift very heavy mountains. God cannot lift an "unliftable" mountain because that would not make sense. He also cannot create an "unliftable" mountain because that also would not make sense, if God can lift everything. God could still lift any mountain that is not defined as "cannot be lifted." For example, God can make a mountain as heavy as he wants, but he cannot make a round square.

Logic

In logic, problems can often be solved by breaking them into smaller pieces. One solves each of the small problems.

Let us see how one can use this for the God Paradox. The paradox is:

- If God can do anything, can He make a mountain which is too heavy for Him to lift?

If one changes this question to a sentence, it becomes:

- God can do anything, which means that He can make a mountain which is too heavy for Him to lift.

We can make this even simpler. First we must see that because God can do anything:

- He can make an unliftable mountain,

- He can lift anything.

Now we can write the sentence as these facts:

- God can do anything.

- God can make an unliftable mountain (because of fact 1).

- God can lift anything (because of fact 1).

- God cannot lift the mountain.

Facts 1, 2 and 3 must always be true. Now we must see if fact 4 is true or false:

- If 4 is true, then 3 must be false (fact 1 must also be false).

The conclusion is that the statement "God can do anything" needs to be qualified. By this logic God cannot do both of two things that are mutually contradictory. C. S. Lewis says that logical contradictions are not a "thing". Rather they are nonsense. The question (and therefore the perceived paradox) is meaningless. Nonsense does not suddenly acquire sense and meaning with the addition of the two words, "God can" before it. [1]

God can

Some people think, "Yes, God is able to do things that make Him not able." They think God is able to do things that are funny to think, "Because", they say, "there is nothing God is not able to do." (See Gospel of Matthew 19:26) However other Bible verses mention things that God cannot do. Hebrews 6:16 says that God cannot lie. Malachi 3:6 says that God cannot change. James 1:3 says that God cannot be tempted by sin.

Some have suggested that God can do things that defy conventional logic. If He lives in other dimensions a different logic may apply. Some say that God cannot make a square circle. This is true in a two dimensional world. However, a cylinder can be a square viewed from the side and a circle viewed from the top. Likewise, a triangle can have three angles that add to more that 180 degrees. This is possible only on a three dimensional surface like a sphere. It can't be done on a two dimensional plane. (Plane geometry). Addition of an additional dimension changes the logic. [2][3]

God is infinite

God is beyond limitation. His strength is infinite. If He chooses to create a mountain that is too heavy for Him to lift he would simultaneously become strong enough to lift it (which actually means he's not omnipotent, because if he can gradually become stronger, then he can't be all powerful). To ask if the creation of such a mountain is possible is to attempt putting a limitation on the limitless.

Job

At the end of the Book of Job, God 'answered Job out of the whirlwind' and asks him: 'Who is this that darkens council by words without knowledge? ..where were you when I laid the foundations of the Earth?' (Job chapter 38, 1-4) In other words, God's powers are beyond human understanding, as human reason itself is part of God's creation in the Book of Genesis.

God Paradox Media

The paradox of the stone uses the idea of an immovable stone to question definitions of omnipotence. Attic kylix of a centaur, c. 510-500 BC.

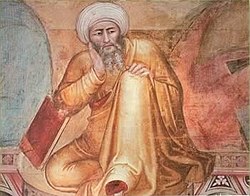

Detail depicting Averroes, who addressed the omnipotence paradox in the 12th century. From the 14th-century Triunfo de Santo Tomás by Andrea da Firenze (di Bonaiuto).

Notes

- ↑ The Problem of Pain, Clive Staples Lewis, 1944 MacMillan

- ↑ "The Fourth Dimension and the Bible". Archived from the original on 2020-07-03. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ↑ "Beyond the Cosmos, Hugh Ross".

Further reading

These references may not be simple to understand.

- Hoffman, Joshua, Rosenkrantz, Gary. "Omnipotence" The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2002 Edition). Edward N. Zalta (ed.) Available online. Accessed 19 April 2006.

- Mackie, J.L. "Evil and Omnipotence." Mind LXIV, No, 254 (1955).

- Wierenga, Edward. "Omnipotence" The Nature of God: An Inquiry into Divine Attributes. Cornell University Press, 1989. Available online. Archived 2001-01-24 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 19 April 2006.