Ivan Pavlov

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov [1] (14 September 1849 – 27 February 1936) was a Russian physiologist, psychologist, and physician.

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov | |

|---|---|

| File:Ivan Pavlov nobel.jpg Nobel Prize portrait | |

| Born | September 14, 1849 |

| Died | February 27, 1936 (aged 86) |

| Nationality | Russian, Soviet |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg University |

| Known for | Classical conditioning Transmarginal inhibition Behavior modification |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1904) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physiologist, psychologist, physician |

| Institutions | Military Medical Academy |

He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1904 for research about the digestive system. Pavlov is widely known for first describing classical conditioning.

Early life and education

The son of a priest, and a theology student, Pavlov turned to science after being influenced by progressive ideas. He took natural sciences at the University of St Petersburg, and got a doctorate in 1878.

Works

In the 1890s, Pavlov was investigating the gastric function of dogs by externalizing a salivary gland so he could collect, measure, and analyze the saliva and what response it had to food under different conditions. He noticed that the dogs tended to salivate before food was actually delivered to their mouths, and set out to investigate this "psychic secretion", as he called it. Pavlov performed and directed experiments on digestion, eventually publishing The work of the digestive glands in 1897, after 12 years of research. His experiments earned him the 1904 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine.[2]

Legacy

The concept for which Pavlov is famous is the "conditioned reflex" he developed with his assistant Ivan Tolochinov in 1901.[3]

As Pavlov's work became known in the West, particularly through the writings of John B. Watson, the idea of "conditioning" as an automatic form of learning became a key concept in the developing specialism of comparative psychology, and the general approach to psychology called behaviourism.

The British philosopher Bertrand Russell was an enthusiastic advocate of the importance of Pavlov's work for philosophy of mind.

Pavlov's research on conditional reflexes greatly influenced not only science, but also popular culture. The phrase "Pavlov's dog" is often used to describe someone who merely reacts to a situation rather than using critical thinking. Pavlovian conditioning was a major theme in Aldous Huxley's dystopian novel, Brave New World, and also to a large degree in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow.

It is popularly believed that Pavlov always signalled the food by ringing a bell. However, his writings also record the use of many stimuli, including electric shocks, whistles, metronomes, tuning forks, and a range of visual stimuli. Catania did not believe Pavlov ever actually used a bell in his famous experiments.[4] Littman tentatively attributed the popular imagery to Pavlov’s contemporaries Vladimir Bekhterev and John B. Watson,[5] until Thomas found several references that clearly said Pavlov did, indeed, use a bell.[6]

It is less widely known that Pavlov's experiments on the conditional reflex included children, some of whom apparently underwent surgical procedures, similar to the dogs, for the collection of saliva.[7]

Ivan Pavlov Media

- Pavlov House Ryazan.JPG

The Pavlov Memorial Museum in Ryazan, Pavlov's former home, built in the early 19th century

- Ivan-Pavlov08.jpg

Ivan Pavlov c. 1883

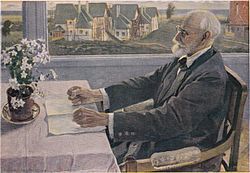

A 1935 portrait of Pavlov by Mikhail Nesterov

Pavlov (right) and his granddaughter Milochka pictured with H. G. Wells in 1924

Monument to Ivan Pavlov in Ryazan

2024 commemorative Russian stamp featuring Ivan Pavlov

References

- ↑ Russian: Иван Петрович Павлов

- ↑ 1904 Nobel prize laureates

- ↑ Todes, Daniel Philip (2002). Pavlov's physiology factory. Baltimore MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 232 et sec. ISBN 0801866901.

- ↑ Catania, A. Charles 1994. Query: did Pavlov's research ring a bell?, PSYCOLOQUY Newsletter, Tuesday, June 7, 1994

- ↑ Littman, Richard A. (1994); Bekhterev and Watson rang Pavlov's bell, Psycoloquy, Vol. 5, No. 49

- ↑ "Thomas, Roger K. 1994. Pavlov's rats "dripped saliva at the sound of a bell", Psycoloquy, 5, No. 80, accessed 22 Aug 2006". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ↑ The brain: a secret history at bbc.co.uk "Mind Control" broadcast on BBC 4 on 11 January 2011

| 40x40px | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |