Natural science

Natural science is the study of the natural world around us. It tries to explain things we see in nature, like why the sky is blue, how plants grow, or what causes lightning. Scientists in this field want to describe what happens, understand why it happens, and even predict what might happen in the future. To do this, they use evidence, real information they get from watching carefully (observation) and running tests (experiments). For example, a scientist might observe how animals behave in the wild or test how different types of soil affect plant growth.[1] To make sure their discoveries are trustworthy, scientists use two important methods. First is peer review, which means other scientists check their work to see if it makes sense and is correct.[2] Second is reproducibility, which means other scientists should be able to repeat the same test and get the same results. These steps help science stay reliable and prevent mistakes from spreading.[3]

Natural science is split into two big parts: life science and physical science. Life science, also called biology, is the study of living things, like plants, animals, and humans. Physical science looks at non-living things and is divided into subjects such as physics (how matter and energy work), astronomy (the study of space and stars), Earth science (the study of Earth, like rocks, weather, and oceans), and chemistry (how different substances are made and how they change). Each of these subjects can be broken down even further into smaller areas, called fields. For example, biology has fields like botany (the study of plants) and zoology (the study of animals). Natural sciences depend on evidence and careful study, so they are called empirical sciences. To make sense of the information they gather, scientists also use tools from formal sciences like math and logic. These tools allow them to turn their observations into measurements and write them as clear rules, often called the “laws of nature.” These laws describe how the world works in ways that can be tested and trusted.[4]

Modern natural science grew out of an older way of studying the world called natural philosophy. In the past, great thinkers like Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, René Descartes, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton argued about the best way to study nature. Some thought math was the most powerful tool, while others believed careful experiments were more important. Even though science today focuses a lot on math and experiments, philosophy still plays a role. Philosophy involves asking big questions, making guesses (called conjectures), and thinking about the assumptions we use when studying nature. These ideas are sometimes hidden in the background, but they are still needed to guide scientific thinking.[5] In the 1500s, people began carefully collecting and organizing information about plants, animals, minerals, and other parts of nature. This was called natural history. Over time, this older way of simply describing and classifying things developed into modern science, which adds experiments and measurements.[6] Today, when we hear the term natural history, it usually means writing or shows that describe nature in a way meant for the general public, such as books, documentaries, or museum exhibits.[7]

Criteria

Philosophers who study science have tried to figure out how to tell real science apart from things that are not scientific. One famous thinker, Karl Popper, suggested a rule called falsifiability. This means that for an idea to be considered scientific, there must be a way to test it and possibly prove it wrong. For example, if someone claims that “all swans are white,” you could test it by looking for swans. Finding just one black swan would prove the idea wrong, which makes it a scientific statement.[8][9]

Scientists also use other important rules to make sure their work is trustworthy. They check for validity, which means the experiments actually measure what they are supposed to. They also check accuracy, which means the results are close to the true values. Another important part is quality control, which includes things like peer review (other scientists check the work) and reproducibility (other scientists can repeat the experiments and get the same results). For example, if a scientist discovers a new way to make plants grow faster, other scientists should be able to do the same experiment and see the same results for it to be considered reliable science.[10][11]

In natural science, when scientists say that something is impossible, they usually mean it is extremely unlikely, not that it is absolutely proven to never happen. Scientists come to this strong belief by looking at a lot of evidence showing that the event has never happened and by using a theory that has successfully predicted many other things. For example, based on physics, we believe it is impossible for a car to travel faster than the speed of light. This belief comes from a theory (Einstein’s theory of relativity) that has been very successful in making predictions.[12]

Even though scientists call something “impossible,” it is not completely unchangeable. If someone ever found a counterexample, an actual case where the “impossible” thing happens, scientists would have to rethink the theory and its assumptions. For instance, if someone actually built a car that went faster than light, physicists would need to go back and figure out why their predictions were wrong.[13]

Branches of natural science

Biology

Biology is the part of science that studies living things. It looks at everything from the very small, like the tiny parts inside cells, to the very large, like entire ecosystems where many animals and plants live together. Biologists study what living things are like, how they are grouped into different categories or species, and how they behave. For example, they might study how birds build nests, how bees collect pollen, or how different types of fish live in the ocean. Biology also studies how species were formed over time, which is called evolution, and how living things interact with each other and their surroundings. For instance, a wolf hunts deer for food, plants grow using sunlight, and fungi help recycle nutrients in the soil.

Some parts of biology have been studied for a very long time. For example, botany (the study of plants), zoology (the study of animals), and medicine (the study of how to keep people healthy) have been around since early human civilizations. Scientists learned about plants, animals, and health from observing the world around them. Microbiology, which is the study of tiny organisms like bacteria and viruses, came much later. It started in the 1600s, after the microscope was invented. The microscope allowed scientists to see things that are too small for our eyes, like bacteria, and study them in detail. Even though these fields existed for a long time, biology was not seen as one single science until the 1800s. Scientists realized that all living things share similarities, like how cells work or how traits are passed from parents to offspring. Because of these shared features, they decided it made more sense to study all living things together rather than separately.

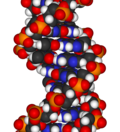

Some of the most important discoveries in biology helped us understand how life works. One big discovery was genetics, which is the study of how traits are passed from parents to their children. For example, if a child has blue eyes like their parent, genetics explains why. Another important idea is evolution by natural selection, which explains how species change over time. For example, giraffes with longer necks could reach more leaves on tall trees, so they were more likely to survive and have babies. Over many generations, this led to giraffes with longer necks. Scientists also discovered the germ theory of disease, which showed that tiny organisms like bacteria and viruses can make people sick. This discovery helped doctors understand diseases and develop ways to prevent and treat them. Finally, biology improved by using tools from chemistry and physics to study cells and molecules. This means scientists can look at the tiny building blocks of life, like DNA or proteins, and understand how they work. For example, using chemistry, scientists can see how enzymes in our bodies help digest food.

Modern biology is divided into different areas depending on what is being studied and how detailed the study is. One area is molecular biology, which studies the chemicals that make up life, like DNA, proteins, and other molecules. For example, molecular biologists study how DNA carries the instructions to build a living thing. Another area is cellular biology, which looks at cells, the tiny units that make up all living things. Cells are like the building blocks of life, and scientists study how they grow, divide, and work. At a larger level, anatomy studies the parts inside an organism, like the heart, lungs, and brain, while physiology looks at how these parts work. For example, physiology explains how your heart pumps blood or how your lungs take in oxygen. Another field is ecology, which studies how different living things interact with each other and with their environment. For example, ecologists might study how bees pollinate flowers or how predators and prey affect each other in a forest.

Earth science

Earth science, also called geoscience, is the study of our planet, Earth, and all the processes that shape it. It is a big field that includes many smaller areas, each focusing on a different part of the Earth. Geology studies rocks, minerals, and the history of the Earth. For example, geologists might examine how mountains form or how earthquakes happen. Geography looks at places on Earth, including landscapes, countries, and how humans interact with the environment. Geophysics studies the physical forces inside the Earth, like gravity and earthquakes, while geochemistry looks at the chemicals that make up rocks, soil, and water.

Climatology studies the climate, or the long-term weather patterns in different places. Glaciology focuses on glaciers and ice, studying how they move and change. Hydrology is about water on Earth, like rivers, lakes, and underground water. Meteorology studies the weather we see every day, like rain, storms, and wind. Finally, oceanography studies the oceans, including waves, currents, and marine life.

Humans have been interested in mining and precious stones for thousands of years, but the scientific study of these things, called economic geology and mineralogy, did not really start until the 1700s. Scientists began studying rocks, minerals, and where valuable resources could be found. In the 1800s, the study of the Earth grew even more, especially paleontology, which is the study of fossils. Fossils help us understand what life and the Earth were like long ago.

In the 1900s, new fields like geophysics (the study of Earth’s physical forces) helped scientists understand how the Earth works on a bigger scale. This led to the theory of plate tectonics in the 1960s. Plate tectonics explains how the Earth’s surface is made of huge moving plates, which cause earthquakes, volcanoes, and the formation of mountains. This theory changed Earth science in the same way that the theory of evolution changed biology. Earth science is very important for finding and using natural resources like oil, gas, and minerals. It is also used in climate research to study changes in the Earth’s weather and environment, and in environmental protection, such as cleaning polluted land or water. All these studies help us understand the Earth and take care of it.

Atmospheric sciences

Atmospheric science is the study of the air and gases around the Earth, also called the atmosphere. Even though it is related to Earth science, it is often treated as its own branch because it has its own methods, ideas, and many specialized areas.

Atmospheric scientists study all the layers of the atmosphere, from the ground where we live up to the very edge of space. They look at things like weather, air pressure, and temperature at different heights. They also study changes over time, from daily weather patterns to long-term climate trends that can last decades or centuries. For example, they might track storms over a few days or study how global temperatures have changed over the past 100 years.

Sometimes, atmospheric science even looks at other planets, studying their climates and atmospheres. For instance, scientists might study the thick clouds on Venus or the thin atmosphere on Mars to understand how these planets are different from Earth. By studying the atmosphere, scientists can predict weather, understand climate change, and learn how air and gases affect life on Earth and other planets.[14]

Oceanography

The serious study of oceans, called oceanography, started in the early to mid-1900s, so it is a relatively young science compared to fields like biology or geology. Even though it is new, there are now many special programs where students can focus specifically on learning about the oceans.

Scientists sometimes debate whether oceanography should be part of Earth science, considered an interdisciplinary science (a mix of different sciences), or treated as a completely separate field. Despite these debates, most scientists agree that oceanography has grown enough to be its own science, with its own methods, ideas, and ways of studying the oceans.

Oceanographers study many things, such as ocean currents, waves, marine life, and how oceans interact with the climate. For example, understanding ocean currents helps scientists predict weather patterns, and studying marine life helps protect ecosystems. Over the past century, oceanography has become an important science for understanding the planet and our environment.

Planetary science

Planetary science, also called planetology, is the study of planets and other objects in space. This includes planets like Earth, as well as gas giants like Jupiter and ice giants like Neptune. It also studies smaller objects like moons, asteroids, comets, and dwarf planets. Most planetary science focuses on objects in our Solar System, but scientists have also started studying exoplanets, planets that orbit other stars. Some of these exoplanets are similar to Earth, called terrestrial exoplanets. Scientists want to understand what these planets are made of, how they move, how they formed, how they interact with other objects, and what their history might be. For example, studying the orbit of a comet can tell us about the early Solar System.

Planetary science combines knowledge from many fields. It comes from astronomy (the study of space) and Earth science (the study of our planet). It includes areas like planetary geology (rocks and landforms on planets), cosmochemistry (chemicals in space), atmospheric science (planetary air and weather), physics, oceanography and hydrology (study of water), glaciology (study of ice), and exoplanetology (study of planets around other stars). Related fields include space physics, which studies how the Sun affects planets and other space objects, and astrobiology, which explores the possibility of life beyond Earth.

Planetary science has two main ways of studying planets and other objects in space: observational and theoretical. Observational research is about looking at and studying objects directly or indirectly. This often happens through space missions, where robotic spacecraft travel to planets, moons, or asteroids to collect data. These spacecraft use remote sensing, which means they gather information from a distance using cameras, sensors, or other instruments. Scientists also do experiments in Earth-based laboratories to compare and test what they see in space. For example, they might study how rocks from Mars react in a lab to understand conditions on the planet. The theoretical side uses math and computer simulations to explain and predict how planets and other space objects behave. For example, scientists can use computer models to see how a planet’s atmosphere might change over thousands of years, or how a comet moves around the Sun.

Planetary scientists are usually found working in astronomy, physics, or Earth science departments at universities or research centers. However, there are also special planetary science institutes around the world that focus only on studying planets and other space objects. To become a planetary scientist, people usually go to graduate school to study subjects like Earth science, astronomy, astrophysics, geophysics, or physics. After that, they specialize in planetary science and focus on research about planets, moons, asteroids, or comets. Planetary scientists share their work at big conferences every year, where they meet other scientists and talk about their discoveries. They also publish their research in peer-reviewed journals, which are magazines where other scientists check their work before it is published. Some planetary scientists work at private research centers and often collaborate with other scientists around the world on joint projects.

Chemistry

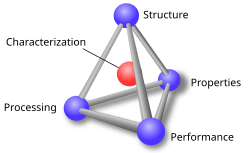

Chemistry is the science that studies matter, which is everything that takes up space and has weight, at the atomic and molecular level. This means chemists look at the tiny building blocks of matter, like atoms and molecules, to understand how they make up everything around us. Chemistry focuses on collections of atoms, such as gases in the air, molecules in water, crystals like table salt or sugar, and metals like iron or gold. Chemists study the composition (what things are made of), the properties (what they are like), and how these materials can change or react with each other. For example, when hydrogen and oxygen combine, they form water, a chemical reaction. Chemistry also looks at how individual atoms and molecules behave and interact, which helps scientists create new materials or products. For example, understanding molecules allows chemists to make medicines, plastics, or even new metals for building cars and airplanes.

Most chemical processes can be studied directly in a laboratory, where scientists use special techniques and tools to handle and change materials. They also rely on their knowledge of the processes happening at the atomic and molecular level to understand what is going on. For example, chemists can mix acids and bases to see how they react, or heat a metal to see how it changes its structure. Chemistry is often called “the central science” because it connects many other fields of science. For example, chemistry helps biologists understand how cells work, physicists understand the behavior of matter, and Earth scientists study the minerals and gases in the planet. This means that chemistry is at the heart of science, helping explain and link ideas across different scientific areas.

Early chemistry grew out of alchemy, which was an old practice that mixed mystical ideas with basic experiments. Alchemists tried things like turning metals into gold or finding the secret to eternal life. Even though many of their ideas were wrong, their experiments laid the groundwork for real science. Modern chemistry started to take shape with scientists like Robert Boyle and Antoine Lavoisier. Robert Boyle is famous for discovering how gases behave, such as how they expand and compress. Antoine Lavoisier developed the law of conservation of mass, which says that matter cannot be created or destroyed during a chemical reaction, it only changes form. For example, when you burn wood, it turns into ash, smoke, and gases, but the total amount of matter stays the same.

The discovery of chemical elements (like hydrogen, oxygen, and gold) and atomic theory (the idea that all matter is made of tiny atoms) helped organize chemistry into a clear, systematic science. Scientists began to understand the different states of matter, solids, liquids, and gases, as well as ions (atoms with an electric charge), chemical bonds (how atoms stick together), and chemical reactions (how substances change into new substances). For example, when hydrogen and oxygen combine, they form water through a chemical reaction. As chemistry became more successful, it led to the growth of the chemical industry, which produces things like medicines, plastics, fertilizers, and cleaning products. This industry is very important and has a big impact on the world economy, because so many everyday products rely on chemical processes.

Physics

Physics is the science that studies the basic building blocks of the universe, the forces they create, and how these forces affect other things. For example, physics explains why apples fall from trees, why planets orbit the Sun, and how magnets pull or push objects. Physics is considered foundational, which means it is the base for many other sciences. For instance, chemistry follows the rules of physics when atoms interact, and biology depends on physics to explain things like blood flow, muscle movement, or how light helps plants grow. Physics uses a lot of mathematics because math helps scientists describe, measure, and predict how things in the universe behave. For example, equations in physics can calculate how fast a ball will fall, how much energy a moving car has, or how strong a magnet’s pull is.

The study of the laws of the universe, which is physics, has a very long history. Early scientists learned mostly by watching nature carefully and doing experiments to see what happens. Over time, people moved from using philosophy and ideas to using systematic experiments and measurements to test their theories. This means scientists now rely on real evidence to know what is true. Some of the most important discoveries in physics include Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and gravity, which explain how objects move and why planets orbit the Sun. Scientists also learned about electricity and magnetism, and how they are connected. Later, Albert Einstein developed the theories of special and general relativity, which describe how space, time, and gravity work on very large scales, like stars and planets. Other important discoveries include thermodynamics, which is the study of heat and energy, and quantum mechanics, which explains how very tiny particles, like atoms and subatomic particles, behave.

Physics is a very large field that studies many different areas. Some examples include quantum mechanics, which looks at how tiny particles like atoms and electrons behave, and theoretical physics, which uses math and ideas to explain how the universe works. Other areas include applied physics, which uses physics to solve practical problems, and optics, which is the study of light and how it behaves, like how lenses work in glasses or cameras. Physics has become so advanced that most scientists specialize in one area instead of studying everything. In the past, famous scientists like Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, and Lev Landau worked in many different areas of physics and made discoveries in multiple fields. Now, because there is so much to learn, physicists usually focus on a specific topic to become experts in that area. This specialization allows scientists to study complex problems in more detail, like understanding black holes, designing better solar panels, or exploring the behavior of tiny particles in quantum computers.

Astronomy

Astronomy is the science that studies things in space, called celestial objects, and the events that happen there. These objects include planets, moons, stars, nebulae (clouds of gas and dust in space), galaxies (huge groups of stars), and comets. Astronomy looks at everything in the universe beyond Earth’s atmosphere, which means everything outside our planet, even objects we can see without a telescope, like the Moon, the Sun, and the planets. People have been studying the sky for thousands of years, making astronomy one of the oldest sciences. For example, early astronomers watched the movements of the Sun, Moon, and stars to make calendars and predict seasons.

There are two main types of astronomy: observational and theoretical. Observational astronomy is about collecting and analyzing data. Astronomers use telescopes and other tools to observe objects in space, and they often rely on the basic rules of physics to understand what they see. For example, they might measure the brightness of a star or track the orbit of a planet. Theoretical astronomy, on the other hand, uses math and computer models to explain how objects and events in space work. Theoretical astronomers try to create models that show how planets form, how stars evolve, or how galaxies move. For example, they might use a computer simulation to predict how a group of stars will behave over millions of years.

This branch of science studies objects and events in space that are outside Earth’s atmosphere, like stars, planets, moons, and galaxies. Astronomers want to understand how these objects form, move, and change over time. The science looks at many different aspects. For example, it studies the physics of stars to understand how they shine, the chemistry of planets to know what they are made of, and the geology of moons or asteroids to see how their surfaces formed. It also studies meteorology in other worlds, like the storms on Jupiter or the dust storms on Mars. Astronomers also study the universe as a whole, including how it started, how it has developed over billions of years, and how galaxies, stars, and planets continue to evolve.

Astronomers try to observe, understand, and create models that explain how these objects behave. Most of the information they use comes from remote observation, which means looking at objects from a distance using telescopes, satellites, and other instruments. Sometimes, astronomers also reproduce space conditions in laboratories to study them more closely. For example, scientists can recreate the molecular chemistry of the gas and dust between stars, called the interstellar medium, to understand how stars and planets form. Astronomy shares a lot with physics, because it uses the same laws to explain motion, energy, and gravity. It also overlaps with Earth science when studying planets. There are many interdisciplinary fields, such as astrophysics (physics of stars and galaxies), planetary science (study of planets and moons), and cosmology (the study of the universe as a whole). Related areas include space physics (effects of the Sun and space environment on planets) and astrochemistry (chemistry in space).

People have been studying stars, planets, and other objects in the sky for thousands of years, going back to ancient civilizations. They watched the movements of the Moon, Sun, and planets to make calendars, predict seasons, and navigate. However, modern astronomy, studying space using a scientific method, began around the mid-1600s. A major step was when Galileo Galilei used a telescope to look at the night sky in more detail. With his telescope, Galileo could see things that had never been observed before, like the mountains on the Moon, the moons of Jupiter, and the phases of Venus.

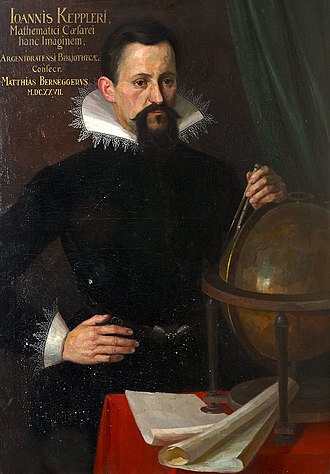

The use of math in astronomy started with scientists trying to understand how planets and stars move. Johannes Kepler made important discoveries about the way planets orbit the Sun, and later Isaac Newton developed celestial mechanics and the laws of gravity, which explained why planets move the way they do. For example, Newton’s laws showed why Earth stays in orbit around the Sun and why the Moon orbits Earth. By the 1800s, astronomy became a more formal and modern science. Scientists started using new tools and instruments to study space in detail. For example, the spectroscope helped them study the light from stars to know what they are made of, and photography allowed them to record images of stars, planets, and comets. Telescopes also became much better, letting astronomers see distant objects more clearly. During this time, professional observatories, special places for studying the sky, were built all over the world.

Interdisciplinary studies

The different natural sciences, like physics, chemistry, and biology, are not completely separate. They often overlap, and scientists create fields that combine two or more sciences to study specific problems. For example, physics is very important for other sciences. Fields like astrophysics study stars and space using physics, geophysics studies the Earth’s physical properties, chemical physics looks at how atoms and molecules behave, and biophysics studies how physical principles affect living things, like how muscles move or how light affects plants. Similarly, chemistry is connected to many other fields. Biochemistry studies the chemicals in living things, physical chemistry looks at how matter behaves at a basic level, geochemistry studies the chemicals in rocks and soil, and astrochemistry studies chemicals in space, like the gases in stars or planets. These overlapping fields show how the sciences work together, using ideas from one area to help understand problems in another. For example, understanding chemistry helps biologists study how cells work, and understanding physics helps astronomers study how planets move.

Environmental science is a field that combines many different sciences to study the environment and how it works. It looks at how physical (like weather), chemical (like pollution), geological (like soil and rocks), and biological (like plants and animals) parts of the environment interact with each other. Environmental scientists are especially interested in how humans affect the environment. For example, cutting down forests, polluting rivers, or building cities can harm biodiversity, which means the variety of plants and animals in an area, and affect sustainability, which is how well the environment can support life over time. This field also uses knowledge from other areas, like economics (to study costs and benefits of protecting the environment), law (to make rules about pollution or resource use), and social sciences (to understand how people behave and make choices about the environment).

Oceanography is a science that studies the oceans and everything in them. Like environmental science, it uses ideas from many different sciences, including physics, chemistry, biology, and geology. Oceanography is divided into specialized areas. For example, physical oceanography studies the physical aspects of the ocean, like waves, currents, and tides, while marine biology focuses on the plants and animals that live in the ocean. Because the ocean is so large and full of different life forms, marine biology is further divided into smaller fields. Some marine biologists specialize in specific species, like studying only dolphins, sharks, or coral. Others might study a particular part of the ocean, like deep-sea creatures or coastal ecosystems.

Some scientific fields combine many different areas of science instead of focusing on just one. These fields often deal with very complex problems that require knowledge from more than one specialty. In other words, scientists in these areas usually need to be experts in multiple subjects to understand and solve problems. For example, nanoscience studies extremely small things, like atoms and molecules, and combines physics, chemistry, and biology. Astrobiology looks for life in space, so it uses biology, astronomy, and chemistry. Complex system informatics studies complicated systems, like traffic patterns or the brain, and uses math, computer science, and physics.

History

The beginnings of natural science go back to the time before humans could write. Early people needed to understand the natural world to survive. They observed animals to know which were safe to hunt, and studied plants to find food or medicine. This knowledge was passed down from one generation to the next, helping people live safely and survive in their environments. Around 3500 to 3000 BC, in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, humans began to write down their observations. This was the first known evidence of what we now call natural philosophy, the early form of natural science. They wrote about things like astronomy, math, and the physical world. However, their main goal was not scientific in the way we think of it today. Instead, their studies were mostly religious or mythological, trying to understand the world through stories or gods rather than using experiments and evidence to explain nature. For example, they might link the movement of the stars to the actions of gods rather than using physics to explain them.[15]

In Ancient China, people also started studying nature in a scientific way. Taoist alchemists and philosophers experimented with elixirs (special potions) to try to extend life or cure illnesses. They believed in yin and yang, which are opposite but connected forces in nature. Yin was linked to femininity and coldness, and yang was linked to masculinity and warmth. They also studied the five phases, fire, earth, metal, wood, and water, which they saw as a cycle of natural changes. For example, water helps wood grow, wood can be burned to make fire, and fire leaves ashes, which become earth. Using these ideas, Chinese philosophers and doctors studied the human body. They described organs as mostly yin or yang, and they learned about how the pulse, heart, and blood flow were connected, hundreds of years before Western medicine recognized it.[16]

In Ancient India, people studied and thought about nature, but only a little evidence survives. Some of their ideas are found in the Vedas, which are sacred Hindu texts. These texts describe the universe as constantly changing, being recycled, and renewed over time. In Ayurveda, the traditional Indian system of medicine, doctors believed that health and illness depended on a balance of three humors: wind, bile, and phlegm. If these humors were balanced, a person stayed healthy. They also believed the body was made of five elements: earth, water, fire, wind, and space. Ayurvedic surgeons were skilled and could perform complex surgeries. They also had a detailed understanding of human anatomy, knowing how organs and the body worked together.[16]

In Ancient Greece, before Socrates, philosophers started studying nature in a more logical and observational way between 600 and 400 BC. They were trying to understand cause and effect in nature, though some magic and myths still influenced their ideas. For example, instead of saying earthquakes or eclipses were caused by angry gods, they tried to explain these events as natural phenomena.[15] One early philosopher, Thales of Miletus (625–546 BC), suggested that earthquakes happened because the world floated on water, and he believed that water was the basic element of nature. Later, in the 5th century BC, Leucippus proposed atomism, the idea that everything in the world is made of tiny, indivisible particles called atoms. Another Greek thinker, Pythagoras, used mathematics to study the stars and planets. He even suggested that the Earth is a sphere, which was an important early step in understanding the shape of our planet.[17]

Aristotelian natural philosophy (400 BC–1100 AD)

After the time of Socrates and Plato, many Greek thinkers focused more on big ideas like right and wrong (ethics), how people should behave (morals), and beauty and art. They did not spend much time studying nature or the physical world. Plato, a very famous philosopher, even said that earlier thinkers cared too much about physical things and not enough about spiritual or religious ideas. But Aristotle, who was Plato’s student, thought differently. He lived from 384 to 322 BC and was very curious about the natural world, plants, animals, and even the stars. In his book History of Animals, he described over 100 animals, such as stingrays, catfish, and bees. He even studied baby chicks by carefully opening eggs at different stages to see how the chicks grew inside. This was one of the first times anyone studied living things so closely, which is why people call him the “father of biology.” Aristotle also wrote about how things move (physics), nature, and space (astronomy). Instead of just guessing, he used a method called inductive reasoning. That means he looked at many examples first, then tried to make a rule or explanation. For example, after seeing that lots of animals breathe, he thought that maybe all animals need air. His ideas were so important that people kept using them for more than a thousand years, until the 1500s.[15]

Aristotle studied nature very seriously, but he mostly treated it as a subject for thinking and explaining instead of testing with experiments like scientists do today. Even so, his ideas inspired many people who came after him. In the early 1st century AD, some Roman thinkers, like Lucretius, Seneca, and Pliny the Elder, wrote books about how nature works. They wanted to describe the “rules” of nature. For example, Pliny the Elder gathered a huge amount of information about plants, animals, and minerals in his famous book Natural History. Later, between the 3rd and 6th centuries, a group of philosophers called the Neoplatonists mixed Aristotle’s ideas with spiritual beliefs. They did not only focus on the physical world, they also tried to connect nature to deeper, religious meanings. In the early Middle Ages, philosophers such as Macrobius, Calcidius, and Martianus Capella studied the universe, especially the stars and planets. They believed space was made of a special, perfect material called aether. Unlike Earth, which they thought was heavy and flawed, the heavens were seen as pure, perfect, and unchanging because of this special substance.[15]

After Aristotle died, people kept reading and sharing his books about nature. His ideas spread during the Byzantine Empire (the eastern part of the Roman world) and the Abbasid Caliphate (a large empire in the Islamic world).[15] In the Byzantine Empire, there was a Christian thinker named John Philoponus. He studied Aristotle’s writings closely but was not afraid to disagree with them. Aristotle often explained how things worked just by using logic and arguments. But Philoponus believed that was not enough, he thought people should also observe and test things in the real world.[18] Philoponus introduced a new idea called the theory of impetus. This went against Aristotle’s physics. Aristotle believed that for something to keep moving, like a rock flying through the air, it had to be constantly pushed. Philoponus said no that once you throw something, it carries its own force (impetus) that makes it keep moving for a while, even without more pushing. For example, when you throw a ball, it keeps going because of the force you gave it, not because something is still pushing it. These ideas were very important because they challenged Aristotle. In fact, centuries later, Galileo Galilei, a famous scientist of the Scientific Revolution, was inspired by Philoponus. Galileo also believed in testing ideas with experiments and observations, which helped transform science forever.[19][20]

Starting in the 9th century, during the Abbasid Caliphate (a powerful Islamic empire), there was a “rebirth” of math and science. Muslim scholars studied the works of earlier Greek and Indian thinkers, but they didn’t just copy them, they added new ideas and made important discoveries about nature, numbers, and the universe. This time of learning was so important that it still affects us today. Many science and math words we use in English actually come from Arabic. For example, alcohol comes from Arabic, algebra (a kind of math with equations and unknown numbers) also comes from Arabic, and so does zenith (the highest point in the sky above you).[17]

Medieval natural philosophy (1100–1600)

For a long time, people in Western Europe did not know much about Aristotle’s books or other Greek writings about nature. That changed around the mid-1100s, when these works were translated from Greek and Arabic into Latin, which was the main language of learning in Europe. Once that happened, European scholars could finally read them. During the Middle Ages, life in Europe began to change. New inventions made farming easier and more productive. For example, the horseshoe protected horses’ feet, the horse collar let horses pull heavy loads without choking, and crop rotation (planting different crops in the same field at different times) kept the soil strong. Because of these improvements, farmers grew more food, the population increased, and more people started moving into towns and cities.[15]

As towns grew, schools were created, often linked to monasteries (religious communities) and cathedrals (big churches) in places like France and England. These schools became important centers of learning. Scholars there studied not only religion but also nature and other subjects. They used logic, careful reasoning and clear arguments, to try to answer big questions. But not everyone agreed with this method. Some people thought that using logic to study religion or nature was dangerous and disrespectful. They even called it heresy, meaning it went against the official teachings of the Church.[15]

In the late Middle Ages, a Spanish philosopher named Dominicus Gundissalinus helped bring new scientific ideas to Western Europe. He translated an important book by a Persian scholar named Al-Farabi into Latin. The book was called On the Sciences and explained how to study the natural world. When Gundissalinus translated it, he used the term Scientia naturalis, which means “natural science”, the study of how nature and the physical world work. In 1150, Gundissalinus also wrote his own book called On the Division of Philosophy. In it, he created the first detailed system in Europe for dividing science into different categories, using ideas from both Greek and Arab thinkers. He explained that natural science was different from math. Natural science looks at real things that move and change, like how animals grow, how plants develop, or how rain forms. Math, on the other hand, deals with numbers, shapes, and abstract ideas that do not physically move. Following Al-Farabi’s system, Gundissalinus divided natural science into eight subjects. Some of these included physics (the study of motion and forces), cosmology (the study of the universe), meteorology (the study of weather), mineral science (the study of rocks and minerals), and plant and animal science (the study of living things).[15]

After Gundissalinus, other philosophers came up with their own ways of dividing science into different parts. In the 1200s, Robert Kilwardby wrote a book called On the Order of the Sciences. He put medicine into a group he called the “mechanical sciences,” which were practical skills people used in everyday life. This group also included farming, hunting, and even theater (acting and plays). For Kilwardby, natural science was different, it was about studying things that move and change in the physical world. Another thinker, Roger Bacon, was an English friar and philosopher who also wrote about natural science. He explained that it was about understanding why things move or stay still. At that time, people believed the world was made up of four elements: fire, air, earth, and water. Bacon said natural science studied how these elements and the things made from them behaved. According to Bacon, natural science also included studying plants, animals, and even the stars, planets, and heavens above.[15]

In the 1200s, a famous Catholic priest and teacher named Thomas Aquinas gave his own definition of natural science. He said it was the study of “mobile beings,” which means things that move, and things that need real physical matter to exist. For example, a tree is not just an idea. It is real because it has wood, leaves, and roots. Without matter, it would not be a tree at all. Most medieval scholars agreed that natural science was about studying the physical world, things that move or change. But they did not always agree on what subjects counted as natural science. Some thought medicine, music, or perspective (the science of vision, like why things look smaller when they are far away) belonged in natural science. Others thought those subjects should go in different categories. Philosophers in the Middle Ages also asked many scientific questions we still think about today, such as, Is there such a thing as completely empty space (a vacuum)? Can motion create heat (like when you rub your hands together to warm them)? What causes rainbows to form? Does the Earth move, or is it completely still? Do basic elemental chemicals really exist (they believed in four: earth, water, air, and fire)? Where in the sky does rain actually form?.[15]

Until the end of the Middle Ages, natural science (the study of nature) was often mixed with ideas about magic and mysterious forces. People wrote about science, then called natural philosophy, in many ways, like long books, encyclopedias (collections of knowledge), and commentaries on Aristotle’s works. The connection between natural philosophy and Christianity was complicated. Some early Christian thinkers, like Tatian and Eusebius, did not trust it because they saw it as part of pagan Greek science (non-Christian beliefs). They worried that studying nature too closely might pull people away from their faith.[15]

Later, Christian philosophers like Thomas Aquinas saw natural science as helpful. They believed that learning about nature could make it easier to understand and explain parts of the Bible. Still, many people remained suspicious of science. This tension showed up clearly in the Condemnation of 1277. Church leaders ruled that philosophy could not be treated as equal to theology (the study of God). They also said science should not be used to argue about religion. In short, the Church wanted theology to stay above philosophy and science. Thinkers like Aquinas and Albertus Magnus tried to keep science and religion separate. Albertus Magnus even wrote in 1271, “I don’t see what one’s interpretation of Aristotle has to do with the teaching of the faith.” He meant that what philosophers say about nature should not control what Christians believe about God.[15]

Newton and the Scientific Revolution (1600–1800)

By the 1500s and 1600s, natural philosophy (what we now call science) began moving past just repeating Aristotle’s old ideas. This happened because more writings from early Greek thinkers were found and translated, giving scholars new things to study. Big changes in the world also pushed science forward. The printing press, invented in the 1400s, made it easy to copy and spread books, so knowledge could reach many more people. New tools like the microscope (to see tiny things) and the telescope (to see far into space) gave scientists powerful ways to observe the world. The Protestant Reformation (a major split in the Christian Church) also encouraged people to question old traditions and authorities.[15]

Exploration changed ideas too. For example, when Christopher Columbus reached the Americas, it showed that the world was larger and more complicated than people had believed. In astronomy, scientists like Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, and Galileo Galilei made careful observations showing that the sun, not the Earth, was at the center of the solar system. This proved many of Aristotle’s old ideas about the heavens were wrong. In the 1600s, philosophers like René Descartes, Pierre Gassendi, Marin Mersenne, Nicolas Malebranche, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Francis Bacon rejected Aristotle’s way of doing science. They thought it was not deep enough and did not explain things well. Instead, they encouraged new methods that focused on observation, experiments, and logical reasoning, the foundations of modern science.[15]

In the 1600s, science was changing fast. You can even see it in the titles of books, like Galileo’s Two New Sciences and Kepler’s New Astronomy. These showed that people were ready to leave behind Aristotle’s old ideas and explore the world in new ways. One of the most important thinkers of this time was Francis Bacon, a philosopher. He believed that science and the arts should be used to understand and control nature. For example, by studying how the world works, people could invent new tools, create better medicines, or improve farming. Bacon thought these discoveries could make life easier and give humans more power to solve problems. Bacon described science as “learning the causes and secret motions of things.” In simple words, he wanted people to figure out why things happen and how they work. He believed this knowledge could help humans do more than ever before by unlocking nature’s secrets. To make this work, Bacon suggested that governments should support science, and that scientists should work together instead of alone. This was a brand-new idea at the time because most learning came from single people or tiny groups, not big teams. Bacon’s vision laid the groundwork for the scientific method and the research institutions we still use today.[15]

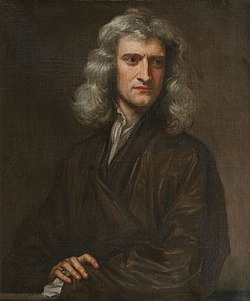

In the 1600s, many scientists, back then called natural philosophers, started to think of nature like a giant machine, kind of like a very complicated clock. Just like you can open up a clock and see how the gears work, they believed you could understand nature by breaking it into smaller parts and studying how each piece worked. Some of the important thinkers of this time were Isaac Newton, Evangelista Torricelli, Francesco Redi, Edme Mariotte, Jean-Baptiste Denis, and Jacques Rohault. They ran experiments to test how the world worked. For example, Torricelli studied air pressure and invented the barometer, which we still use today to measure the atmosphere for weather forecasts. Redi proved that life does not just appear out of nowhere (like flies suddenly showing up in rotting meat). Instead, he showed that living things come from other living things. This was also the time when scientific societies (groups of scientists working together) and scientific journals (like magazines for sharing discoveries) were created. Thanks to the printing press, new ideas spread quickly, leading to what we now call the Scientific Revolution, a period when science made huge breakthroughs. One of the biggest moments was in 1687, when Isaac Newton published his famous book Principia Mathematica (The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy). In it, he explained the laws of motion and gravity. These ideas became the foundation for science for more than 200 years, until the 1800s, when even deeper laws of physics were discovered.[15]

Experts today do not fully agree on when real science began. Some scholars, like Andrew Cunningham, Perry Williams, and Floris Cohen, argue that the old way of studying nature, called natural philosophy, was not true science. They believe real science only began during the Scientific Revolution in the 1600s and 1700s. For example, Cohen said the big change happened when science finally separated from natural philosophy and became its own field of study. Other historians, like Edward Grant, see it differently. He thinks the Scientific Revolution happened when people started using exact sciences, like optics (the study of light), mechanics (the study of motion and forces), and astronomy (the study of space), to answer the bigger questions that natural philosophy had been asking for centuries. Grant also points to Isaac Newton as a major turning point. Newton showed that nature follows clear mathematical rules that never change. For example, his laws of motion and gravity proved that the same rules that make an apple fall from a tree also control the planets moving in space.[15]

The Scientific Revolution in the 1600s was a time when people started studying nature in a completely new way. For hundreds of years, most science was based on the ideas of Aristotle, but now scientists wanted to test things for themselves instead of just trusting old teachings. The biggest change was the invention of the scientific method, a way to discover the truth about the world. First, scientists collected data (information) by making careful measurements and running experiments that other people could repeat. Then, they made a hypothesis, an educated guess or explanation for what they saw. They then tested the hypothesis to see if it could be proven wrong. If it passed the tests, it became a stronger explanation of how nature worked. This made science much more reliable than just guessing or arguing. For example, instead of only asking, “Does heat come from motion?” scientists could now design experiments to measure heat and motion and find out the real answer. Because of this, science slowly changed from being mostly philosophical discussion to being a structured, evidence-based way of understanding nature.[17]

Isaac Newton, an English scientist and mathematician, was one of the most important figures in the Scientific Revolution. He built on the ideas of earlier astronomers like Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, and Johannes Kepler to create some of the most famous rules in science: the laws of motion and the law of gravity. Before Newton, people thought Earth and space followed different rules. For example, they believed an apple falling from a tree followed one set of rules, while planets moving in the sky followed another. Newton proved they were actually the same. His law of gravity showed that the force pulling an apple to the ground is the same force that keeps planets moving around the Sun. He even explained that the ocean tides happen because the Moon’s gravity pulls on Earth’s water. Newton also changed how people used math in science. Instead of only measuring things, he used mathematics to explain why things happened. For example, he showed the connection between force, motion, and gravity using equations.[17]

In the 1700s and 1800s, scientists kept building on Newton’s work and discovered a new type of force in nature: electricity and magnetism, also called electromagnetism. Some of the key scientists who worked on this were Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, Alessandro Volta, and Michael Faraday. Faraday had a big idea. He said that forces do not just act across empty space with nothing in between (like how Newton described gravity). Instead, they act through something called fields. A field is like an invisible area around an object where its force can be felt. For example, a magnet has a magnetic field around it, and that’s why it can pull a paperclip toward it without even touching it. Later, another scientist named James Clerk Maxwell combined all these discoveries into one complete theory. He used both math and experiments to show that space is full of invisible energy fields that can affect each other. He also discovered that these fields can carry waves, this is how light and radio waves travel through space.[17]

During the Scientific Revolution, people also made big discoveries in chemistry. At first, many believed in the phlogiston theory, which said that when something burned, it released an invisible substance called “phlogiston” into the air. But this idea was wrong. A French chemist named Antoine Lavoisier helped prove why. Another scientist, Joseph Priestley, had discovered oxygen, and Lavoisier showed that burning happens because materials combine with oxygen in the air. This process is called oxidation. For example, when wood burns in a fire, it is not letting out phlogiston, it is reacting with oxygen. Lavoisier also made a list of 33 elements (basic substances that everything is made of) and helped create the system we still use today to name chemicals. This made it much easier for scientists to share their discoveries.[17] At the same time, biology was just beginning to grow as a science. The main job then was to organize living things. A Swedish scientist named Carl Linnaeus led this work. In 1735, he created a system to group plants, animals, and other life, and gave each species a scientific name in Latin. For example, humans became Homo sapiens. His naming system is still used all over the world today.[22]

19th-century developments (1800–1900)

By the 1800s (the 19th century), science became more organized and professional. Instead of just being studied by curious people or philosophers, science was now taught in schools, universities, and scientific institutions. This made it more official, and people started calling it natural science. During this time, the word “scientist” was invented. A man named William Whewell came up with it in 1834 while reviewing a book called On the Connexion of the Sciences by Mary Somerville, a famous science writer. Before that, people usually called scientists natural philosophers.[23] Even though the word “scientist” was created in the early 1800s, most people did not start using it regularly until the late 1800s. For many decades, scientists were still called natural philosophers, even though they were doing modern science just like today.[24][25]

Modern natural science (1900–present)

In 1923, two American scientists, Gilbert N. Lewis and Merle Randall, wrote a famous book called Thermodynamics and the Free Energy of Chemical Substances.[26] In it, they explained that all the natural sciences, the study of the world and universe, can be divided into three big branches: mechanics, electrodynamics, and thermodynamics. Mechanics is about how things move and interact, like why a ball rolls down a hill or how a swing works. Electrodynamics studies electricity and magnetism, like how magnets pull objects or how lightning happens. Thermodynamics is about heat and energy, like why boiling water turns into steam or how engines work.[27]

Today, scientists usually divide natural science in a simpler way. Life sciences study living things, like plants (botany) and animals (zoology). Physical sciences study non-living things, like physics, chemistry, astronomy, and Earth science.

See also

- Branches of science

- Empiricism

- List of academic disciplines and sub-disciplines

- Natural history

- Natural Sciences (Cambridge), for the Tripos at the University of Cambridge

Natural Science Media

References

- ↑ "What Is Natural Science? 5 Definitions | University of the People |". www.uopeople.edu. 2021-06-10. Retrieved 2025-09-29.

- ↑ "What is Peer Review? | Wiley". authorservices.wiley.com. Retrieved 2025-09-29.

- ↑ "The Role of Reproducibility and Replicability in Science", Reproducibility and Replicability in Science, National Academies Press (US), 2019-05-07, retrieved 2025-09-29

- ↑ Lagemaat, Richard van de (2011-05-26). Theory of Knowledge for the IB Diploma Full Colour Edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-66996-3.

- ↑ Gauch, Hugh G. (2015). Scientific method in practice (Elektronische Ressource ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01708-4.

- ↑ Ogilvie, Brian W. (2008). The science of describing: natural history in Renaissance Europe (Paperback ed.). Chicago, [Ill.]: Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-62088-6.

- ↑ "Education and Outreach: Exhibiting the scientific process – PALAEONTOLOGY[online]". Retrieved 2025-09-29.

- ↑ "Criterion of falsifiability | Falsificationism, Popper, Hypotheses | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2025-09-29.

- ↑ Thornton, Stephen (1997-11-13). "Karl Popper". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Archive.

- ↑ Fidler, Fiona; Wilcox, John (2018-12-03). "Reproducibility of Scientific Results". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ Gundersen, Odd Erik (2021-05-17). "The fundamental principles of reproducibility". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 379 (2197). doi:10.1098/rsta.2020.0210. ISSN 1364-503X.

- ↑ Psillos, Stathis (2022), Zalta, Edward N.; Nodelman, Uri (eds.), "Realism and Theory Change in Science", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2022 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2025-09-29

- ↑ "Scientific Change | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". Retrieved 2025-09-29.

- ↑ "Planetary & Exoplanetary Atmospheres". scienceandtechnology.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2025-09-29.

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 15.12 15.13 15.14 15.15 15.16 Grant, Edward (2007). A history of natural philosophy: from the ancient world to the nineteenth century. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68957-1.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Magner, Lois N. (2002). A History of the Life Sciences, Revised and Expanded (3rd ed.). Baton Rouge: Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-8247-0824-5.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Barr, Stephen M. (2023). A Student's Guide to Natural Science. The Preston A. Wells jr. guides to the major disciplines. Washington, D.C: Regnery Gateway. ISBN 978-1-932236-92-7.

- ↑ "John Philoponus, Commentary on Aristotle's Physics, pp". homepages.wmich.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-01-11. Retrieved 2025-09-30.

- ↑ Wildberg, Christian (2016), Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), "John Philoponus", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2016 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2025-09-30

- ↑ Lindberg, David C. (2007). The beginnings of western science: the European scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context, prehistory to A.D. 1450 (2nd ed.). Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ↑ "Johannes Kepler: His Life, His Laws and Times". 24 September 2016. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst (1982). The growth of biological thought: diversity, evolution, and inheritance (2. print ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ.Press. ISBN 978-0-674-36445-5.

- ↑ Holmes, Richard (2009). The age of wonder: how the romantic generation discovered the beauty and terror of science (Paperback ed.). London: Harper Press. ISBN 978-0-00-714953-7.

- ↑ Ross, Sydney (1962). "Scientist: The story of a word". Annals of Science. 18 (2): 65–85. doi:10.1080/00033796200202722. ISSN 0003-3790.

- ↑ "'Review of On The Connexion of the Physical Sciences by Mrs Somerville' (1834)". Taylor & Francis. 2024-10-28. doi:10.4324/9781003548249-15/review-connexion-physical-sciences-mrs-somerville-1834-william-whewell.

- ↑ Lewis G. N., Randall M. (1923). Thermodynamics and the free energy of chemical substances. Library Genesis. MGH.

- ↑ Huggins, Robert A. (2010). Energy Storage. SpringerLink Bücher. Boston, MA: Springer US. ISBN 978-1-4419-1023-3.