Iron

- This article is about iron the metal. For the tool called iron, see ironing.

Iron is a chemical element and a metal. It is the most common chemical element on Earth (by mass), and the most widely used metal. It makes up much of the Earth's core, and is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust. Its atomic number is 26, because each atom has 26 protons.

The metal is used a lot because it is strong and cheap. Iron is the main ingredient used to make steel. Raw iron is magnetic (attracted to magnets), and its compound magnetite is permanently magnetic.

In some regions iron was used around 1200 BCE. That event is considered the transition from Bronze Age to Iron Age.

Properties

Physical properties

Iron is a grey, silvery metal. It is magnetic, though different allotropes of iron have different magnetic qualities. Iron is easily found, mined and smelted, which is why it is so useful. Pure iron is soft and very malleable.

Chemical properties

Iron is reactive. It reacts with most acids like sulfuric acid. It makes ferrous sulfate when it reacts with sulfuric acid. This reaction with sulfuric acid is used to clean metal.

Iron reacts with air and water to make rust. When the rust flakes off, more iron is exposed allowing more iron to rust. Eventually, the whole piece of iron is rusted away. Other metals like aluminum do not rust away. Iron can be alloyed with chromium to make stainless steel, which does not rust under most conditions.

Iron powder can react with sulfur to make iron(II) sulfide, a hard black solid. Iron also reacts with the halogens to make iron(III) halides, like iron(III) chloride. Iron reacts with the hydrohalic acids to make iron(II) halides like iron(II) chloride.

Chemical compounds

Iron makes chemical compounds with other elements. Normally the other element oxidizes iron. Sometimes two electrons are taken and sometimes three. Compounds where iron has two electrons taken are called ferrous compounds. Compounds where iron has three electrons taken are called ferric compounds. Ferrous compounds have iron in its +2 oxidation state. Ferric compounds have iron in its +3 oxidation state. Iron compounds can be black, brown, yellow, green, or purple.

Ferrous compounds are weak reducing agents. Many of them are green or blue. The most common ferrous compound is ferrous sulfate.

Ferric compounds are oxidizing agents. Many of them are brown. The most common ferric compound is ferric oxide, the same thing as rust. One reason why iron rusts is because ferric oxide is an oxidizing agent. It oxidizes iron, rusting it even under paint. That is why if there is a small scratch in the paint, the whole thing can rust.

Iron(II) compounds

Compounds in the +2 oxidation state are weak reducing agents. They are normally light colored. They react with oxygen in air. They are also known as ferrous compounds.

- Iron(II) sulfide, a shiny chemical that reacts with acids to release hydrogen sulfide, found in the ground

- Iron(II) sulfate, a blue-green crystalline chemical made by reacting sulfuric acid with steel, used to reduce poisons like chromate in concrete

- Iron(II) chloride, a pale green crystalline chemical made by reacting hydrochloric acid with steel

- Iron(II) hydroxide, a dark green powder made by electrolyzing water with an iron anode, reacts with oxygen and turns brown

- Iron(II) oxide, black, flammable, rare

Mixed oxidation state

These compounds are rare; only one is common. They are found in the ground.

- Iron(II,III) oxide, a black mineral, used as ore of iron, contains iron in the +2 and +3 oxidation state.

Iron(III) compounds

Compounds in the +3 oxidation state are normally brown. They are oxidizing agents. They are corrosive. They are also known as ferric compounds.

- Iron(III) oxide, rust, red-brown, dissolves in acid

- Iron(III) chloride, poisonous and corrosive, dissolves in water to make dark brown acidic solution. Made by reacting iron with hydrochloric acid and an oxidizing agent

- Iron(III) nitrate, light purple, corrosive, used in etching

- Iron(III) sulfate, rare, light brown, dissolves in water. Made by reacting iron with sulfuric acid and an oxidizing agent.

Where iron is found

There is a lot of iron in the universe because it is the end point of the nuclear reactions in large stars. It is the last element to be produced before the violent collapse of a supernova scatters the iron into space.

The metal is the main ingredient in the Earth's core. Near the surface it is found as a ferrous or ferric compound. Some meteorites contain iron in the form of rare minerals. Normally iron is found as hematite ore in the ground, much of which was made in the Great Oxygenation Event. Iron can be extracted from the ore in a blast furnace. Some iron is found as magnetite.

There are iron compounds in meat. Iron is an essential part of the hemoglobin in red blood cells.

Making iron

Iron is made in large factories called ironworks by reducing hematite with carbon (coke). This happens in large containers called blast furnaces. The blast furnace is filled with iron ore, coke and limestone. A very hot blast of air is blown in, where it causes the coke to burn. The extreme heat makes the carbon react with iron ore, taking off the oxygen from iron oxides, and making carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide is a gas and it leaves the mix. There is some sand in with the iron. The limestone, which is made of calcium carbonate, turns into calcium oxide and carbon dioxide when the limestone is very hot. The calcium oxide reacts with the sand to make a liquid called a slag. The slag is drained, leaving only the iron. The reaction will leave pure liquid iron in the blast furnace, where it can be shaped and hardened after cooling down. Almost all ironworks are today part of steel mills, and almost all iron is made into steel.

There are many ways to work iron. Iron can be hardened by heating a piece of metal and splashing it into cold water. It can be softened by heating it and allowing it to slowly cool. It can also be stamped by a heavy press. It can be pulled into wires. It can be rolled to make sheet metal.

In the United States, much of the iron was taken from the ground in Minnesota and then sent by ship to Indiana and Michigan where it was made into steel.

Uses

As a metal

Iron is used more than any other metal. It is strong and cheap. It is used to make buildings, bridges, nails, screws, pipes, girders, and towers.

Iron is not very reactive, so it is both easy and cheap to extract from ores. It is very strong once made into steel, and is used to reinforce concrete.

There are different types of iron. Cast iron is iron made by the way described above in the article. It is hard and brittle. It is used to make things like storm drain covers, manhole covers, and engine blocks (the main part of an engine).

Steel is the most common form of iron. Steels come in several forms. Mild steel is steel with a low percentage of carbon. It is soft and easily bent, but it does not crack easily. It is used for nails and wires. Carbon steel is harder but more brittle. It is used in tools.

There are other types of steel. Stainless steel, because of the chromium content, is rust resistant, and nickel-iron alloys can remain strong at high temperatures. Other steels can be very hard, depending on the alloys added.

Wrought iron is easily shaped and used to make fences and chains.

Very pure iron is soft, and can rust (oxidize) easily. It is also fairly reactive.

As compounds

Iron compounds are used for several things. Iron(II) chloride is used to make water clean. Iron(III) chloride is also used. Iron(II) sulfate is used to reduce chromates in cement. Some iron compounds are used in vitamins.

Nutrition

Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional deficiency in the world.[1][2][3]

Human bodies need iron to help oxygen get to our muscles, because it is at the heart of some essential macromolecules such as hemoglobin. Many cereals have some added iron (the element metal iron).[4][5] It is added to cereal in the form of tiny metal filings. It is even possible to see the slivers sometimes by taking an extremely strong magnet and putting it into the box. The magnet will attract these pieces of iron. Eating these small metal shavings are not harmful to our body.[6]

Iron is most available to the body when added to amino acids – iron in this form is ten to fifteen times more digestible than than it is as an element.[7] Iron is also found in meat, for example steak. Iron provided by diet supplements is in the form of a chemical, such as Iron(II) sulfate, which is cheap and is absorbed well. The body will not take up more iron than it needs, and it usually needs very little. The iron in red blood cells is recycled by a system which breaks down old cells. Loss of blood by injury or parasite infection may be more serious.[8]

Toxicity

Iron is toxic when large amounts are taken into the body. When too many iron pills are taken, people (especially children) get sick. Also, there is a genetic disorder which damages the regulation of iron levels in the body.

IronChemical Compounds Media

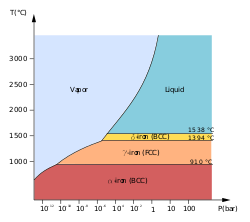

Low-pressure phase diagram of pure iron

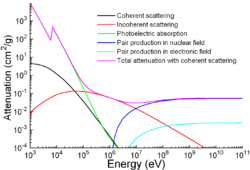

Photon mass attenuation coefficient for iron

A polished and chemically etched piece of an iron meteorite, believed to be similar in composition to the Earth's metallic core, showing individual crystals of the iron-nickel alloy (Widmanstatten pattern)

Ochre path in Roussillon

Pourbaix diagram of iron

Comparison of colors of solutions of ferrate (left) and permanganate (right)

Related pages

References

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2002). "Iron deficiency – United States, 1999–2000". MMWR. 51 (40): 897–9. PMID 12418542.

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Identifiers at line 630: attempt to index field 'known_free_doi_registrants_t' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Identifiers at line 630: attempt to index field 'known_free_doi_registrants_t' (a nil value). electronic-book ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1 ISSN 1559-0836 electronic-ISSN 1868-0402

- ↑ "Testing the fortitude of iron in cereals". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2010-01-29.

- ↑ Adams, Cecil. Return of the Straight Dope. New York: Ballantine Books, 1994

- ↑ Felton, Bruce. One of a Kind. New York: William Morrow and Co., 1992

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Identifiers at line 630: attempt to index field 'known_free_doi_registrants_t' (a nil value).

- ↑ Andrews N.C. 2000. Disorders of iron metabolism. New England Journal of Medicine. Related correspondence, published in NEJM 342:1293-1294.