Earthquake

An earthquake is when Earth's tectonic plates shake and move Earth's surface. Strong earthquakes damage buildings.

Disturbances in the Earth cause earthquakes. Different tectonic plates are slowly moving. When they get stuck, tension builds up in them. Earthquakes occur when tectonic plates suddenly break free, so they start moving quickly. The first point of an earthquake's rupture is called its hypocenter or focus. The epicenter is the point at ground level directly above the hypocenter.

People who study earthquakes are called seismologists. Many earthquakes can occur in a small area in a short period of time. The sudden release of stress in the tectonic plates sends waves of energy that travel through the Earth. Seismology studies the cause, recurrence, type and magnitude of earthquakes.

The effect of an earthquake can be measured with a seismometer. A seismometer detects the tremors of the earth and plots the tremors on a seismograph. The strength or magnitude of an earthquake can be measured using the Richter scale. The Richter scale was invented by Charles Francis Richter in 1935. The scale is numbered 0-10. A 2 on this scale is a tremor that is not easily recorded. And damage of size 5 (or more) in a wide area. The largest earthquake ever measured had a magnitude of 9.5.

No one can tell when an earthquake will happen. But we know where earthquakes are likely to occur in the future, such as near fault lines. An earthquake under the ocean can create a huge wave called a tsunami. Tsunamis can also cause a lot of destruction. [1]

Zones

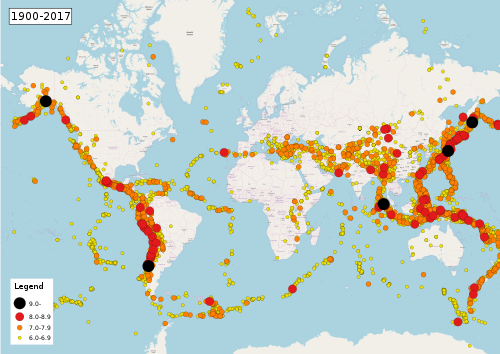

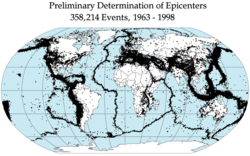

Earthquake zones are concentrated in some parts of the world. The first is the Pacific belt, which circles the Pacific Ocean. This part is the biggest seismic belt: it has the most active earthquakes and the most volcanoes.[2]

The second part is the Alpide belt. It includes the seismic activities from Sumatra, to the Himalayas, to south Europe and north Africa, to the Atlantic Ocean.

These belts are along the edges of tectonic plates. The tectonic plates push on each other and make great amounts of tension.

History

Earthquakes sometimes hit cities and kill hundreds or thousands of people. Most earthquakes happen along the Pacific Ring of Fire but the biggest ones mostly happen in other places. Tectonically active places are places where earthquakes or volcanic eruptions are regularly repeated.

Causes of an earthquake

Earthquakes are caused by tectonic movements in the Earth's crust. The main cause is when tectonic plates ride one over the other, causing orogeny (mountain building), and severe earthquakes.[3]

The boundaries between moving plates form the largest fault surfaces on Earth. When they stick, motion between the plates leads to increasing stress. This continues until the stress rises and breaks, suddenly allowing sliding over the locked portion of the fault. This releases the stored energy as shock waves. The San Andreas fault in San Francisco, and Rift valley fault in Africa are faults like this. Earthquakes caused by volcanic eruptions can be quite devastating. However, these earthquakes are confined to areas around active volcanoes.

Often the causes are not known, except in the most general terms. An example is the largest earthquake in the history of the United States: the 1811–1812 New Madrid earthquakes. These are described as caused by very deep shifts in ancient rock formations. In other words, the cause is not known in detail.

In areas of intense mining activity, often the roofs of underground mines collapse and minor tremors take place. These are called collapse earthquakes.

Earthquake fault types

There are three main types of geological fault that may cause an earthquake: normal, reverse (thrust) and strike-slip. Normal faults occur mainly in areas where the crust is being extended. Reverse faults occur in areas where the crust is being shortened. Strike-slip faults are steep structures where the two sides of the fault slip horizontally past each other.

Earthquake clusters

Most earthquakes form part of a sequence, related to each other in terms of location and time.[4] Most earthquake clusters consist of small tremors which cause little to no damage, but there is a theory that earthquakes can recur in a regular pattern.[5]

A foreshock is an earthquake that happens before a larger earthquake, called the mainshock.

An aftershock is an earthquake that happens after a previous earthquake, the mainshock. An aftershock is in the same place of the main shock but always of a smaller magnitude. Aftershocks are formed as the crust adjusts to the effects of the main shock.[4]

Earthquake swarms are sequences of earthquakes striking in a specific area within a short period of time. They are different from earthquakes followed by a series of aftershocks by the fact that no single earthquake in the sequence is obviously the main shock, therefore none have notably higher magnitudes than the other. An example of an earthquake swarm is the 2004 activity at Yellowstone National Park.[6]

Sometimes a series of earthquakes happen in a sort of earthquake storm, where the earthquakes strike a fault in clusters, each triggered by the shaking or stress redistribution of the previous earthquakes. Similar to aftershocks but on adjacent segments of fault, these storms happen over the course of years, and with some of the later earthquakes as damaging as the early ones. Such a pattern happened in the North Anatolian fault in Turkey in the 20th century.[7][8]

Tsunami

A tsunami is a chain of fast moving waves in the ocean caused by powerful earthquakes. They are very serious challenges for people's safety and for earthquake engineering. Those waves can flood coastal areas, destroy houses and even swipe away whole towns.[9] This is a danger for the whole mankind.

Unfortunately, tsunamis cannot be prevented. However, there are warning systems[10] which may warn the population before the big waves reach the land to let them enough time to rush to safety.

Earthquake-proofing

Earthquake-proof buildings are constructed to withstand the destructive force of an earthquake. This depends upon its type of construction, shape, mass distribution, and rigidity. Different combinations are used. Square, rectangular, and shell-shaped buildings can withstand earthquakes better than skyscrapers. To reduce stress, a building's ground floor can be supported by extremely rigid, empty columns, while the rest of the building is supported by flexible columns inside the empty columns. Another method is to use rollers or rubber pads to separate the base columns from the ground, allowing the columns to shake parallel to each other during an earthquake.

To help prevent a roof from collapsing, builders make the roof out of light-weight materials. Outdoor walls are made with stronger and more reinforced materials such as steel or reinforced concrete. During an earthquake, flexible windows may help hold the windows together so they don't break.

- REDIRECT Template:See also

EarthquakeEarthquake Clusters Media

Earthquake epicenters occur mostly along tectonic plate boundaries, especially on the Pacific Ring of Fire.

Three types of faults:*A. Strike-slip*B. Normal*C. Reverse

Aerial photo of the San Andreas Fault in the Carrizo Plain, northwest of Los Angeles

Collapsed Gran Hotel building in the San Salvador metropolis, after the shallow 1986 San Salvador earthquake

The 2023 Turkey–Syria earthquakes ruptured along segments of the East Anatolian Fault at supershear speeds; more than 50,000 people died in both countries.

Magnitude of the Central Italy earthquakes of August and October 2016 and January 2017 and the aftershocks (which continued to occur after the period shown here)

The Messina earthquake and tsunami took about 80,000 lives on December 28, 1908, in Sicily and Calabria.

Sources

- ↑ "What is it about an earthquake that causes a tsunami? | U.S. Geological Survey". www.usgs.gov. 28 April 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2025.

- ↑ "Earthquake Zones | Physical Geography". courses.lumenlearning.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ↑ "Science of Earthquakes Seismic Zones". PR Fire. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "What are aftershocks, foreshocks, and earthquake clusters?". Archived from the original on 2009-05-11. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- ↑ "Repeating earthquakes". United States Geological Survey. January 29, 2009. Archived from the original on April 3, 2009. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- ↑ "Earthquake swarms at Yellowstone". USGS. Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- ↑ Amos Nur (2000). "Poseidon's horses: plate tectonics and earthquake storms in the late Bronze Age Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 27: 43–63. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0431. ISSN 0305-4403. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ "Earthquake storms". Horizon (BBCtv series). 1 April 2003. Archived from the original on 2019-10-16. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- ↑ "USGS Poster of the Near the East Coast of Honshu, Japan Earthquake of 11 March 2011 - Magnitude 8.9". Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ↑ "Pacific Tsunamy Warning Center". Archived from the original on 2011-03-13. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

Other websites

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- PBS NewsHour - Predicting Earthquakes

- USGS – Largest earthquakes in the world since 1900 Archived 2009-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- The Destruction of Earthquakes Archived 2009-02-08 at the Wayback Machine - a list of the worst earthquakes ever recorded

- Recent Quakes WorldWide Archived 2017-09-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Earthquake Citizendium

- Real Time Seismicity European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre (EMSC)