Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces that survived into the Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The empire had its capital at Constantinople, survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD and continued to exist until the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453.

Roman Empire | |

|---|---|

| 330/395–1453b | |

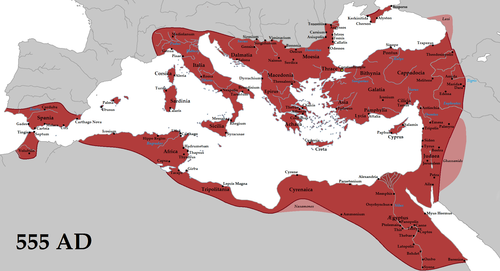

The empire in 555 under Justinian the Great, at its greatest extent since the fall of the Western Roman Empire (its vassals in pink) | |

The territorial evolution of the Eastern Roman Empire under each imperial dynasty until its fall in 1453. | |

| Status | Eastern division of the Roman Empire[1] |

| Capital | Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul)c |

| Common languages | |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Rhōmaîoi |

| Notable emperors | |

• 306–337 | Constantine I (first) |

• 408–450 | Theodosius II |

• 474–475, 476–491 | Zeno |

• 527–565 | Justinian I |

• 582–602 | Maurice |

• 610–641 | Heraclius |

• 717–741 | Leo III |

• 797–802 | Irene |

• 867–886 | Basil I |

• 976–1025 | Basil II |

• 1081–1118 | Alexios I |

• 1143–1180 | Manuel I |

• 1261–1282 | Michael VIII |

• 1449–1453 | Constantine XI |

| Historical era | Late Antiquity to Late Middle Ages |

• | 1 April 286 |

| 11 May 330 | |

• Final East–West division after the death of Theodosius I | 17 January 395 |

• Fall of the West; deposition of Romulus | 4 September 476 |

• Assassination of Julius Nepos | 9 May 480 |

• Early Muslim conquests; start of the Dark Ages | 634–750 |

• Battle of Manzikert; loss of Anatolia due to following civil war | 26 August 1071 |

• Sack of Constantinople by Catholic crusaders | 12 April 1204 |

• Reconquest of Constantinople | 25 July 1261 |

| 29 May 1453 | |

• Fall of Morea | 29 May 1460 |

• Fall of Trebizond | 15 August 1461 |

| Population | |

• 457 | 16,000,000f |

• 565 | 26,000,000 |

• 775 | 7,000,000 |

• 1025 | 12,000,000 |

• 1320 | 2,000,000 |

| Currency | Solidus, denarius and hyperpyron |

During most of its existence, the empire remained the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in the Mediterranean region. Its citizens continued to refer to their empire as the Roman Empire and to themselves as Romans, a term that Greeks continued to use for themselves into Ottoman times. Modern historians distinguish the Byzantine Empire from the earlier Roman Empire because the imperial seat moved from Rome to Byzantium, the empire integrated Christianity, and Greek replaced Latin as the most common language.

History

During the high period of the Roman Empire, known as the Pax Romana period, the western parts of the empire went through Latinization, but the eastern parts of the empire maintained to a large degree their Hellenistic culture. Several events from the 4th to 6th centuries mark the period of transition during which the Roman Empire's Greek East and Latin West diverged.

Constantine I (r. 324–337) reorganised the empire, made Constantinople the capital, and legalised Christianity. Under Theodosius I (r. 379–395), Christianity became the state religion, and other religious practices were forbidden. In the reign of Heraclius (r. 610–641), the empire's military and administration were restructured, and Greek was gradually adopted for official use in place of Latin.

Middle Ages

The borders of the empire fluctuated through several cycles of decline and recovery. During the reign of Justinian I (r. 527–565), the empire reached its greatest extent after the fall of the western Roman Empire by reconquering much of the historically Roman western Mediterranean coast, including, Africa, Italy, and Rome, which it held for two more centuries.

The Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 exhausted the empire's resources, and during the early Muslim conquests of the 7th century, the empire lost its richest provinces (Egypt and Syria) to the Rashidun Caliphate. It then lost Africa to the Umayyads in 698, before the empire was stabilized by the Isaurian dynasty.

The Macedonian dynasty (9th–11th centuries) expanded the empire again but ended with defeat by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. Civil wars and the ensuing Seljuk invasion led to the loss of most of Asia Minor. The empire recovered during the Komnenian restoration, and until the Fourth Crusade, Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest city in Europe.

Interregnum

The empire was first dissolved during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, when Constantinople was sacked by the Latins (Catholic Europeans from the West), and the territories that the empire had governed were divided into competing Byzantine Greek and Latin realms. Despite the eventual recovery of Constantinople in 1261, the Byzantine Empire remained a mere regional power for the final two centuries of its existence. Its remaining territories were progressively annexed by the Ottomans during the Byzantine–Ottoman Wars in the 14th and the 15th centuries.

Fall

The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 marked the end of the Byzantine Empire. Refugees fleeing the city after its capture settled into Italy and other parts of Europe and helped to ignite the Renaissance. The Empire of Trebizond was conquered eight years later, when its capital surrendered to Ottoman forces after it had been besieged in 1461. The fall of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottomans is sometimes used to mark the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the early modern period.

Name

The Byzantine Empire did not get that name until a century after its fall. The empire was known at the time as the following:

- the "Roman Empire" or the "Empire of the Romans" (Latin: Imperium Romanum, Imperium Romanorum; Greek: Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων Basileia tōn Rhōmaiōn, Ἀρχὴ τῶν Ῥωμαίων Archē tōn Rhōmaiōn),

- "Romania" (Latin: Romania; Greek: Ῥωμανία Rhōmania),[n 1]

- the "Roman Republic" (Latin: Res Publica Romana; Greek: Πολιτεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Politeia tōn Rhōmaiōn),

- "Graecia" (Greek: Γραικία meaning "land of the Greeks"),[3]

- "Rhomais" (Greek: Ῥωμαΐς meaning "Rome").[4]

Beginning (330–476 AD)

In 324, Roman Emperor Constantine I moved the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to the Greek city of Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople. By the 5th century, the Roman Empire had lost its territories in the west, and the Western Roman Empire had been taken over by Germanic peoples during the Migration period. The surviving parts of the Roman Empire became known as the Eastern Roman Empire and is now called the Byzantine Empire.

Crisis (476–717 AD)

Wars in west

The Eastern Roman Empire tried to take back Rome and the rest of Italian Peninsula from the Germanic peoples. Between 530 and 555 AD, the Byzantine Greeks won many battles and took back Rome.

The Byzantines controlled Rome for a long time. Eventually, more Germanic peoples came, and Italy was lost again. Later, Avars and Slavs took parts of Southeast Europe from the Byzantines. After the 560s, invaders slowly conquered the Balkans except for parts of modern Greece and Albania. Bulgars from the steppes formed the First Bulgarian Empire north of the Byzantine Empire. At first, both the Avars and the Bulgars were Turkic peoples. They ruled over the Slavic people, who were called Sklavinai, and slowly absorbed the Slavic language and culture.

Wars in east

After Rome had been captured by the Germanic peoples, the Eastern Roman Empire continued to control what are now Egypt, Greece, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey. However, another empire, known as the Persian or the Sassanid Empire, tried to take the lands for itself. Between 224 and 628, the Greco-Romans and the Persians fought many battles, and many men were killed in the fighting. Eventually, the Persians were defeated in 627 by Emperor Heraclius in what is now Iraq, near the ancient city of Nineveh, which allowed the Byzantines to keep those lands.

The centuries-long struggle between the Byzantines and the Persians shaped the political and religious landscape of the Middle East, leaving behind a complex legacy that continues to influence the region today.

Then, another enemy appeared, the Arabs. The Byzantines did not have much money to spend on war because of their battles with the Persians and so they could not withstand the Arabs. Palestine, Syria, and Egypt were lost between 635 and 645 by Heraclius. However, the Byzantines defended Asia Minor (now in Turkey), and the Arabs advance stopped there. Heraclius ordered the use of Greek as the only language of the empire, erased forever the name "Eastern Roman Empire" and cut the last links with Roman Civilisation.::..

Recovery (717–1025 AD)

In 718, the Arabs were defeated but left the Byzantines very weak. In the west, the Byzantines fought the Bulgarians many times. Some battles were successful, but many emperors died fighting. Over time, the Byzantine Empire weakened as it lost land to outside invaders.

Recovery in the west

Between 1007 and 1014, Emperor Basil II ambitiously attacked Bulgaria many times and eventually won a great victory. Later, he fully recaptured Greece and recovered it for the empire. He then went on to take over Bulgaria, which was fully conquered in 1018.

Recovery in the east

In the east, the Arabs once again became a threat to the Byzantines. However, Basil II kept attacking and won many more victories. Much of Syria was restored to the empire, and Turkey and Armenia were secured. After 1025, the Arabs were no longer a threat to the Byzantines.

Decline (1025–1453 AD)

Start of decline (1025–1071)

After Basil II died, many unskilled emperors came to the throne, wasted the empire's money, and reduced its army. That meant that it could not defend itself well against enemies if they attacked. Later, the Byzantines relied on mercenaries, soldiers who fought for money, not for their country. That made them less loyal and reliable and more expensive. The mercenaries allowed military generals to come to power and to grab it from the elaborate bureaucracy, a system of administration in which tasks are divided by departments.

Rise of Turks (1071–1091)

A large number of people, known as the Turks, rode on horseback from Central Asia and attacked the Byzantine Empire. The Seljuk Empire took most of Anatolia from the Byzantines by 1091. However, it received help from people in Western Europe in what is known as the First Crusade. Many knights and soldiers left to help the Byzantines and to secure Jerusalem for the Christians. The city was then controlled by the Muslims.

Survival (1091–1185)

The Byzantine Empire survived and, with the help of the other European empires, took back half of Anatolia from the Turks, who managed to hold the other half of the region. The Byzantines survived primarily because it had three good emperors in a row, which allowed the empire to recover from their recent conflicts.

Another weakening (1185-1261)

The next few emperors ruled poorly and spent much of the existing treasury on many mercenary soldiers.

In the west, the Western Europeans betrayed the Byzantines and attacked their capital in the Fourth Crusade, Constantinople. The sack of Constantinople in 1204 effectively ended the Empire (which split up into smaller Greek states who fought for control over each other), as the crusaders established the Latin Empire known as Frankokratia to the Byzantines, which lasted until 1261 when the Empire of Nicaea captured Constantinople and Michael VIII Palaiologos was declared Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans soon after, restoring the Byzantine Empire.

Fall to Ottoman’s Turks (1261–1453)

After the Byzantines had taken back Constantinople, they were too busy fighting the Europeans who had betrayed them and so they could not find enough Soldiers or Money to fight the Turks' new Ottoman Empire. All of Asia Minor had been lost by 1331, and in 1369, the Turks crossed over from Turkey and into Greece. They took over much of Greece firmly and along all their neighbour countries in the Aegean Sea between 1354 and 1450.::.!’!

The Byzantines lost so much Land, Money and Soldiers that they became very weak and begged for help from the Western Europeans. France, Spain; and Italy plus it’s Pope sent Soldiers and ships to help the Byzantines when the Turks attacked Constantinople in April 1453. The Byzantines were badly outnumbered, however, and the walls of Constantinople were “…” damaged badly by the cannons that were used by the Turks. In late May 1453, the Turks captured Constantinople by entering through one of the gates along the walls, and the empire came to an end.::.

The City was plundered for three days. In the end, those who had not been able to escape were deported to Edirne, Bursa, and other Ottoman cities. There was nobody in the city except for the Jews of Balat and the Genoese of Pera. Constantinople became the capital of the Ottoman Empire until it fell in the early 20th century (1298-1925). The city was later renamed Istanbul, and the Turkish capital was moved to Ankara, a city in Asia Minor.::.!’!

Legacy

The Byzantines had several achievements:

- They used good architecture that is still used

- They preserved the Greek language and culture

- They had cities with plumbing, which is still in use

- They protected part of Christian Europe from Islamic invasions

- They preserved many Roman political traditions that had been lost in Western Europe

- They produced much fine art with a distinctive style

- They kept a lot of knowledge that can be read about today

- They made several inventions like the flamethrower and "Greek fire", a kind of napalm

- They made advances in many fields like political studies, diplomacy and military sciences

- They were the protectors and sponsors of the Eastern Church, which later becomes the Orthodox Church

- They built many beautiful churches, some of which are now mosques, in what are now Turkey and Greece; they are made from or inspired by Byzantine buildings

Byzantine Empire Media

The Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, very important during the 717–718 siege

Gold solidus of Leo III (left), and his son and heir, Constantine V (right)

The seizure of Edessa (1031) by the Byzantines under George Maniakes and the counterattack by the Seljuk Turks

A mosaic from the Hagia Sophia of Constantinople (modern Istanbul), depicting Mary and Jesus, flanked by John II Komnenos (left) and his wife Irene of Hungary (right), 12th century

The partition of the empire following the Fourth Crusade, c. 1204[5]

The siege of Constantinople in 1453, depicted in a 15th-century French miniature

Related pages

Notes

References

- ↑ "Byzantine Greek language". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ↑ Fossier & Sondheimer 1997, p. 104.

- ↑ Constantelos 2001–2002

- ↑ Cinnamus 1976, p. 240.

- ↑ Laiou 2008, p. 280; Kaldellis 2023, pp. 733–734; Reinert 2002, pp. 250–253; Angold 2009b, p. 731.

Sources

- Ahrweiler, Helene (1975). L'Ideologie Politique de l'Empire Byzantine [The Political Ideology of the Byzantine Empire] (in French). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Baynes, Norman Hepburn; Moss, Henry St. Lawrence Beaufort (1948). Byzantium: An Introduction to East Roman Civilization. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Cartwright, Mark (13 April 2018). "Byzantine Government". Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- Cinnamus, Ioannes (1976). Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus. New York and West Sussex: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-04080-6.

- Clover, F. M.; Humphreys, R. S. (1989). Tradition and Innovation in Late Antiquity. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299120009.

- Constantelos, Demetrios I. (2001–2002). "Μαρτυρίες για την Ταυτότητα των Βυζαντινών και των Ρωμιών σε Ελληνικές Πηγές" (in Greek). Πεμπτουσία. http://www.myriobiblos.gr/texts/greek/constantelos_martiries_ch1.html#3.

- Fossier, Robert; Sondheimer, Janet (1997). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26644-0.

- Lemerle, Paul (1971). Le Premier Humanisme Byzantin [The First Byzantine Humanism] (in French). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Linnér, Sture (1994). Bysantinsk kulturhistoria [History of Byzantine Culture] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Norstedt. ISBN 978-9-11-941512-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

Other websites

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- World History Encyclopedia: Byzantine Empire

- Roman Emperors (De Imperatoribus Romanis)

- 18 Centuries of Roman Empire: A Cartography by Howard Wiseman

- 12 Byzantine Rulers: The History of the Byzantine Empire (Lars Brownworth)

- 18 centuries of Roman Empire by Howard Wiseman (Maps of the Roman/Byzantine Empire throughout its lifetime).

- Byzantine & Christian Museum

- Dumbarton Oaks: Byzantine Studies

- Byzantium: Byzantine Studies on the Internet Archived 2014-10-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Translations from Byzantine Sources: The Imperial Centuries, c. 700–1204

- De Re Militari: The Society for Medieval Military History

- Medieval Sourcebook: Byzantium Archived 2014-08-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Bibliography on Byzantine Material Culture and Daily Life (University of Vienna)

- Constantinople Home Page

- Byzantium in Crimea: Political History, Art and Culture.

- Byzanzforschung: Institute for Byzantine Studies of the Austrian Academy of Sciences