Logarithm

Logarithms or logs are a part of mathematics. They are related to exponential functions. A logarithm tells what exponent (or power) is needed to make a certain number, so logarithms are one of the inverse operations of exponentiation (the other one being roots). Historically, they were useful in multiplying or dividing large numbers.

An example of a logarithm is [math]\displaystyle{ \log_2 8=3 }[/math]. In this logarithm, the base is 2, the power is 8 and the answer is 3. In this case, the exponentiation function would be:

[math]\displaystyle{ 2^3=2\times2\times2=8 }[/math]

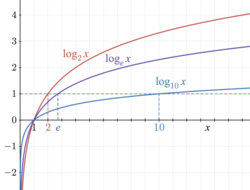

The most common types of logarithms are common logarithms, where the base is 10, binary logarithms, where the base is 2, and natural logarithms, where the base is [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \approx2.71828 }[/math].[1][2]

History

Logarithms were first used in India in the 2nd century BCE. The first to use logarithms in modern times was the German mathematician Michael Stifel (around 1487–1567). In 1544, he wrote down the following equations: [math]\displaystyle{ q^m q^n=q^{m+n} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{q^m}{q^n}=q^{m-n} }[/math]. This is the basis for understanding logarithms. For Stifel, [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] had to be whole numbers. John Napier (1550–1617) did not want this restriction, and wanted a range for the exponents.

According to Napier, logarithms express ratios: [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] has the same ratio to [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math], as [math]\displaystyle{ c }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] if the difference of their logarithms matches. Mathematically: [math]\displaystyle{ \log a-\log b=\log c-\log d }[/math]. At first, base [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] was used (even though the number had not been named yet). Henry Briggs proposed to use 10 as a base for logarithms, as such logarithms are very useful in astronomy.[2]

Relationship with exponential functions

A logarithm tells what exponent is needed to make a certain number, so logarithms are one of the inverse operations of exponentiation.

Just as an exponential function has three parts, a logarithm has three parts as well: a base, a power (also called exponent) and an argument (sometimes called the answer).

The following is an example of an exponential function:

- [math]\displaystyle{ 2^3=8 }[/math]

In this function, the base is 2, the power is 3 and the answer is 8.

This exponential equation has an inverse, its logarithmic equation:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log_2 8=3 }[/math]

In this equation, the base is 2, the power is 3 and the answer is 8.

Difference to roots

Addition has one inverse operation: subtraction. Also, multiplication has one inverse operation: division. However, exponentiation actually has two inverse operations: the root and the logarithm. The reason why this is the case has to do with the fact that exponentiation is not commutative.

The following example illustrates this:

- If [math]\displaystyle{ x+2=3 }[/math], then one can use subtraction to find out that [math]\displaystyle{ x=3-2 }[/math]. This is the same if [math]\displaystyle{ 2+x=3 }[/math]: one also gets [math]\displaystyle{ x=3-2 }[/math]. This is because [math]\displaystyle{ x+2 }[/math] is the same as [math]\displaystyle{ 2+x }[/math].

- If [math]\displaystyle{ x\cdot2=3 }[/math], then one can use division to find out that [math]\displaystyle{ x=\frac32 }[/math]. This is the same if [math]\displaystyle{ 2\cdot x=3 }[/math]: one also gets [math]\displaystyle{ x=\frac32 }[/math]. This is because [math]\displaystyle{ x\cdot2 }[/math] is the same as [math]\displaystyle{ 2\cdot x }[/math].

- If [math]\displaystyle{ x^2=3 }[/math], then one can use the square root to find out that [math]\displaystyle{ x=\sqrt3 }[/math]. However, if [math]\displaystyle{ 2^x=3 }[/math], then one cannot use the root to find out [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. Rather, one has to use the binary logarithm to find out that [math]\displaystyle{ x=\log_2 3 }[/math].

This is because [math]\displaystyle{ 2^x }[/math] usually is not the same as [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 }[/math] (for example, [math]\displaystyle{ 2^5=32 }[/math] but [math]\displaystyle{ 5^2=25 }[/math]).

Uses

Logarithms can make multiplication and division of large numbers easier, because adding logarithms is the same as multiplying, and subtracting logarithms is the same as dividing.

Before calculators became popular and common, people used logarithm tables in books to multiply and divide.[2] The same information in a logarithm table was available on a slide rule, a tool with logarithms written on it.

Aside from computations, logarithm also has many other real-life applications:

- Logarithmic spirals are common in nature. Examples include the shell of a nautilus, or the arrangement of seeds on a sunflower.

- In chemistry, the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the activity of hydronium ions (H3O+, the form H+ takes in water) is the measure known as pH. The activity of hydronium ions in neutral water is 10−7 mol/L at 25 °C, hence a pH of 7. (This is a result of the equilibrium constant, the product of the concentration of hydronium ions and hydroxyl ions, in water solutions being 10−14 M2.)

- The Richter scale measures earthquake intensity on a base 10 logarithmic scale.[1]

- In astronomy, the apparent magnitude measures the brightness of stars logarithmically, since the eye also responds logarithmically to brightness.

- Musical intervals are measured logarithmically as semitones. The interval between two notes in semitones is the base [math]\displaystyle{ 2^{\frac{1}{12}} }[/math] logarithm of the frequency ratio (or equivalently, 12 times the base 2 logarithm). Fractional semitones are used for non-equal temperaments. Especially to measure deviations from the equal tempered scale, intervals are also expressed in cents (hundredths of an equally-tempered semitone). The interval between two notes in cents is the base [math]\displaystyle{ 2^{\frac{1}{1200}} }[/math] logarithm of the frequency ratio (or 1200 times the base 2 logarithm). In MIDI, notes are numbered on the semitone scale (logarithmic absolute nominal pitch with middle C at 60). For microtuning to other tuning systems, a logarithmic scale is defined filling in the ranges between the semitones of the equal tempered scale in a compatible way. This scale corresponds to the note numbers for whole semitones. (see microtuning in MIDI Archived 2008-02-12 at the Wayback Machine).

Common logarithms

Base 10 Logarithms are called common logarithms. They are usually written without the base. For example:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log100=2 }[/math]

This is true because:

- [math]\displaystyle{ 10^2=100 }[/math]

Natural logarithms

Logarithms to base [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] are called natural logarithms. The number [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] is nearly 2.71828, and is also called the Eulerian constant after the mathematician Leonhard Euler.

The natural logarithms can take the symbols [math]\displaystyle{ \log_e x }[/math] or, more commonly, [math]\displaystyle{ \ln x }[/math].[3] Some authors prefer the use of natural logarithms as [math]\displaystyle{ \log x }[/math],[4] (and usually mention it on preface pages). There is no single standard of what "[math]\displaystyle{ \log x }[/math]" means, so it is important to see how each author defines it.

Common bases for logarithms

| base | abbreviation | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{ld} }[/math] | Very common in computer science (binary) |

| [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \ln }[/math] | The base of this is the Eulerian constant [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math]. This is the most common logarithm used in pure mathematics. |

| 10 | [math]\displaystyle{ \log_{10} }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \log }[/math] (sometimes also written as [math]\displaystyle{ \lg }[/math]) | Used in some sciences like chemistry and biology. |

| any number [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \log_n }[/math] | This is the general way to write logarithms |

Properties of logarithms

Logarithms have many properties. For example:

Properties from the definition of a logarithm

This property is straight from the definition of a logarithm:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log_n(n^a)=a }[/math]

For example

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log_2(2^3)=3 }[/math], and

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log_2(\frac12)=-1 }[/math], because [math]\displaystyle{ \frac12=2^{-1} }[/math].

The logarithm to base [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] of a number [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math], is the same as the logarithm of [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] divided by the logarithm of [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math]. That is,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log_b a=\frac{\log a}{\log b} }[/math]

For example, let [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] be 6 and [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] be 2. With calculators we can show that this is true (or at least very close):

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log_2 6=\frac{\log 6}{\log 2} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log_2 6\approx2.584962 }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ 2.584962\approx\frac{0.778151}{0.301029}\approx2.584970 }[/math]

The results above had a small error, but this was due to the rounding of numbers.

Since it is hard to picture the natural logarithm, we find that, in terms of a base ten logarithm:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ln x=\frac{\log x}{\log e}\approx\frac{\log x}{0.434294} }[/math], where 0.434294 is an approximation for the logarithm of [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math].

Operations within logarithm powers

Logarithms which multiply inside their power can be changed as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log ab=\log a+\log b }[/math]

For example,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log1000=\log(10\cdot10\cdot10)=\log10+\log10+\log10=1+1+1=3 }[/math]

Similarly, logarithm which divides inside the argument can be turned into a difference of logarithm (because it is the inverse operation of multiplication):

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log(\frac ab)=\log a-\log b }[/math]

Logarithm tables, slide rules, and historical applications

Before electronic computers, logarithms were used every day by scientists. Logarithms helped scientists and engineers in many fields such as astronomy.

Before computers, the table of logarithms was an important tool.[5] In 1617, Henry Briggs printed the first logarithm table. This was soon after Napier's basic invention. Later, people made tables with better scope and precision. These tables listed the values of [math]\displaystyle{ log_b x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b^x }[/math] for any number [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] in a certain range, at a certain precision, for a certain base [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] (usually [math]\displaystyle{ b=10 }[/math]). For example, Briggs' first table contained the common logarithms of all integers in the range 1–1000, with a precision of 8 digits.

Since the function [math]\displaystyle{ f(x)=b^x }[/math] is the inverse function of [math]\displaystyle{ log_b x }[/math], it has been called the antilogarithm.[6] People used these tables to multiply and divide numbers. For example, a user looked up the logarithm in the table for each of two positive numbers. Adding the numbers from the table would give the logarithm of the product. The antilogarithm feature of the table would then find the product based on its logarithm.

For manual calculations that need precision, performing the lookups of the two logarithms, calculating their sum or difference, and looking up the antilogarithm is much faster than performing the multiplication by earlier ways.

Many logarithm tables give logarithms by separately providing the characteristic and mantissa of [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], that is to say, the integer part and the fractional part of [math]\displaystyle{ log_{10}x }[/math].[7] The characteristic of [math]\displaystyle{ 10\cdot x }[/math] is one plus the characteristic of [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], and their significands are the same. This extends the scope of logarithm tables: given a table listing [math]\displaystyle{ log_10 x }[/math] for all integers [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] ranging from 1 to 1000, the logarithm of 3542 is approximated by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log_{10}3542=\log_{10}(10\cdot354.2)=1+\log_{10}354.2\approx1+\log_{10}354 }[/math]

Another critical application was the slide rule, a pair of logarithmically divided scales used for calculation, as illustrated here:

Numbers are marked on sliding scales at distances proportional to the differences between their logarithms. Sliding the upper scale appropriately amounts to mechanically adding logarithms. For example, adding the distance from 1 to 2 on the lower scale to the distance from 1 to 3 on the upper scale yields a product of 6, which is read off at the lower part. Many engineers and scientists used slide rules until the 1970s. Scientists can work faster using a slide rule than using a logarithm table.[8]

Logarithm Media

The graph of the logarithm base 2 crosses the x-axis at x = 1 and passes through the points (2, 1), (4, 2), and (8, 3), depicting, e.g., log2(8) = 3 and 23 = 8. The graph gets arbitrarily close to the y-axis, but does not meet it.

The 1797 Encyclopædia Britannica explanation of logarithms

The graph of the logarithm function logb (x) (blue) is obtained by reflecting the graph of the function b'x (red) at the diagonal line (x = y).

The graph of the natural logarithm (green) and its tangent at x = 1.5 (black)

The natural logarithm of t is the shaded area underneath the graph of the function f(x) = 1/x.

The logarithm keys (LOG for base 10 and LN for base e) on a TI-83 Plus graphing calculator

Related pages

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "The Ultimate Guide to Logarithm — Theory & Applications". Math Vault. 2016-05-08. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "logarithm | Rules, Examples, & Formulas". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Natural Logarithm". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ↑ "Compendium of Mathematical Symbols". Math Vault. 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ↑ Campbell-Kelly, Martin (2003), The history of mathematical tables: from Sumer to spreadsheets, Oxford scholarship online, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-850841-0, section 2

- ↑ Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene A., eds. (1972), Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables (10th ed.), New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0, section 4.7., p. 89

- ↑ Spiegel, Murray R.; Moyer, R.E. (2006), Schaum's outline of college algebra, Schaum's outline series, New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-145227-4, p. 264

- ↑ Maor, Eli (2009), E: The Story of a Number, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-14134-3, sections 1, 13