New Forest

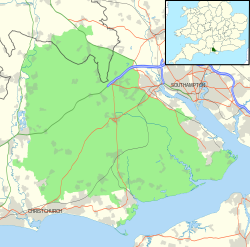

New Forest is an area of southern England. It includes one of the largest remaining pieces of open pasture land, heathland and forest in the heavily-populated south East of England.[1] It covers south-west Hampshire and extends into south-eastern Wiltshire and towards easter, Dorset.

| New Forest National Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN Category II (National Park) | |

The Beaulieu River cuts through Longwater Lawn, about 4 km (2 mi) from its source near Lyndhurst | |

| Location | Hampshire, England |

| Nearest city | Southampton |

| Area | New Forest National Park: 566 km2 (219 sq mi) New Forest: 380 km2 (150 sq mi) |

| Visitors | 14.75 million (est) (in 2009) |

The name also refers to the New Forest National Park, which has similar boundaries. The New Forest District is a subdivision of Hampshire that covers most of the forest. There are many villages dotted around the area, and several small towns in the forest and around its edges. Originally established as a royal forest by William the Conqueror around 1079 for hunting, the New Forest still retains much of its natural and cultural heritage. It includes ancient woodlands, wild open heathlands, and a beautiful coastline, with free-roaming animals like New Forest ponies, cattle, donkeys, and pigs that help shape the landscape.

History

The New Forest was created as a royal forest by King William I in about 1079 for the royal hunt, mainly of deer.[2] It was created at the expense of more than 20 small hamlets and isolated farmsteads and so it was "new" at the time as a single compact area.[3]

It was first recorded as "Nova Foresta" in Domesday Book in 1086. It is the only forest that the book describes in detail. "Probably no action of the early Norman kings is more notorious than their creation of the New Forest".[4][5][6]

Two of William's sons died in the Forest: Prince Richard in 1081 and William II in 1100. Local folklore asserted that it was punishment for the crimes that William had committed when he created the New Forest. A 17th-century writer provides detail:

"William the Conqueror (for the making of the said Forest a harbour for Wild-beasts for his Game) caused 36 Parish Churches, with all the Houses thereto belonging, to be pulled down, and the poor Inhabitants left succourless of house or home. But this wicked act did not long go unpunished, for his Sons felt the smart thereof; Richard being blasted with a pestilent Air; Rufus shot through with an Arrow; and Henry his Grand-child, by Robert his eldest son, as he pursued his Game, was hanged among the boughs, and so dyed. This Forest at present affordeth great variety of Game, where his Majesty oft-times withdraws himself for his divertisement."[7]

The common rights were confirmed by statute in 1698. The New Forest became a source of timber for the Royal Navy, and plantations were created in the 18th century for that purpose. During the Great Storm of 1703, about 4000 oak trees were lost. The naval plantations affected the rights of the commoners, but the Forest gained new protection under an Act of Parliament in 1877.

Modern era

The New Forest Act 1877 confirmed the historic rights of the commoners and prohibited the enclosure of more than 65 km2 (25 sq mi) at any time. It also reconstituted the Court of Verderers as representatives of the Commoners, rather than the Crown. The felling of broadleaved trees and their replacement by conifers began during the First World War to meet the wartime demand for wood. Further encroachments were made during the Second World War. This process is being reversed in places, with some plantations being returned to heathland or broadleaved woodland, but Rhododendron remains a problem.

As of 2005, roughly 90% of the New Forest is still owned by the Crown, whose lands have been managed by the Forestry Commission since 1923 andnow fall mostly inside the new National Park.

Further New Forest Acts followed in 1949, 1964 and 1970. The New Forest became an Site of Special Scientific Interest in 1971 and was made the New Forest Heritage Area in 1985, with more planning controls added in 1992. The New Forest was proposed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in June 1999[8] and became a national park in 2005.[9]

Common rights

The purpose of forest laws was to preserve the New Forest as a place for royal deer hunting, and interference with the King's deer and its forage was punished. The inhabitants of the area (commoners) had pre-existing rights of common.

The rights were to bring horses and cattle (but only rarely sheep) to the forest to graze (common pasture), to gather fuel wood, to cut peat for fuel, to dig clay (marl), and to turn out pigs between September and November to eat fallen acorns and beechnuts (pannage or mast).

Grazing and pannage are still important to the Forest's ecology. Pigs can eat acorns without a problem, whereas to ponies and cattle large numbers of acorns can be poisonous. Pannage always lasts 60 days, but the start date varies according to the weather and when the acorns fall. The Verderers decide when pannage will start each year. At other times, the pigs must be taken in and kept on the owner's land, with the exception that pregnant sows, known as privileged sows, are always allowed out, providing they are not a nuisance and return to the Commoner's holding at night.[10] Commoners must have backup land outside the Forest to hold these depastured animals if necessary.

Commons rights used to be attached to particular plots of land or to particular hearths. Grazing of commoners' ponies and cattle is an essential part of the management of the gorest and helps to keep the heathland, bog, grassland and wood-pasture habitats and their wildlife in good shape. The ancient practice came under pressure, as the rising house prices in the area stopped local commoning families from moving into new homes, which have the rights attached. That meant that the next generation could not become commoners until their parents passed on the house and rights.

Those rights are now dissasociated. Efforts by the New Forest Commoners Defence Association, Verderers and associated bodies mean there is a burgeoning economy in the New Forest and a chance for some commoners to earn well above the minimum wage and additional help for their farming interests. That will help the commoners continue to preserve the Forest.

New Forest Media

Alder trees by the Beaulieu river at Fawley Ford, north of Beaulieu

Lyndhurst, the "capital" of the New Forest, in 2020

Ponies walking the streets in Burley

Picnic area in Bolderwood

References

- ↑ "Commoning in the New Forest". New Forest District Council. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "History of the New Forest". New Forest National Park. 2009. Archived from the original on 13 October 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "Old Hampshire Gazetteer (citing Muir, 1981)". port.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2013-08-24.

- ↑ Loyn, Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, 2nd ed. 1991:378-82.

- ↑ H. C. Darby. Domesday England, pp. 198–199. Cambridge University Press, 1986. ISBN 0-521-31026-1

- ↑ Young, Charles R. (1979). The Royal Forests of Medieval England. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0-8122-7760-0.

- ↑ "Blome, Richard (1673) Britannia: or, a geographical description of the kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland". Thomas Ryecroft. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2013-08-24.

- ↑ Entry on the UNESCO Tentative List.

- ↑ History of the New Forest National Park[dead link].

- ↑ Darby H.C. 1948. Review: The Preservation of the New Forest: Report of the New Forest Committee. Geographical Journal. 112, 1/3, pp. 87-91.