Paleontology

Palæontology or paleontology is the study of fossils of living things, and their phylogeny (evolutionary relationships).[1] It depends on basic sciences such as zoology, botany and historical geology. The term palaeobiology implies that the study will include the palaeoecology of the groups in question.

In palaeozoology, the evolution of those animal phyla with fossil records are studied. In palaeobotany, fossil plants are studied. In historical geology the formation, sequence and dating of rock strata give information about past environments.

A fossil is any kind of life that is more than ten thousand years old and preserved in any form that we can study today.[2] The fossil record is always incomplete, and later discoveries may extend the known survival of a group. See Lazarus taxon.

Some palaeontologists study fossils of microorganisms, living things that are too small to see without a microscope, while other palaeontologists study fossils of giant dinosaurs.

- Vertebrate palaeontology: the palaeontology of vertebrate animals

- Invertebrate palaeontology: the palaeontology of invertebrate animals

Paleontology Media

Bust of the paleontologist Georges Cuvier (left) and a cast skeleton of Palaeotherium magnum (named by Cuvier in 1804, right), Cuvier Museum of Montbéliard

The geologic time scale, proportionally represented as a log-spiral with some major events in Earth's history. A megaannus (Ma) represents one million (106) years.

Cuvier's 1812 unpublished illustration of the extinct mammal Anoplotherium

Ernst Haeckel's "tree of life", illustrating an early understanding of how evolution relates to classification

Archaeological excavations in the Middle Paleolithic cave site of the Ghamari Cave in Zagros Mountains

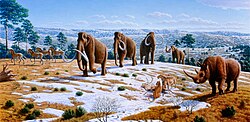

Restoration of ice age megafauna during the Pleistocene in northern Spain

Related pages

References

- ↑ Prothero, Donald R. 2007. Evolution: what the fossils say and why it matters. Columbia University Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-231-13962-5

- ↑ Levin, Harold L. 2005. The Earth through time. 8th ed, Wiley, N.Y. Chapter 4: The fossil record.