Ruminant

A ruminant is an ungulate that eats and digests plant-based food such as grass.

| Ruminants | |

|---|---|

| |

| White-tailed deer | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Clade: | Cetruminantia |

| Clade: | Ruminantiamorpha Spaulding et al., 2009 |

| Suborder: | Ruminantia Scopoli, 1777 |

| Families | |

Ruminating mammals include cattle, goats, sheep, giraffes, bison, yaks, water buffalo, deer, camels, alpacas, llamas, wildebeest, antelope, pronghorn, and nilgai. All of them are Artiodactyla, cloven-hoofed animals.[1]

The word "ruminant" comes from the Latin word ruminare which means "to chew over again". They have a more complex digestive system than other vegetarians. Digestion of food is always done mainly by microorganisms, and in ruminants it is digested twice.

An example of a grass-eater which is not a ruminant is the horse. Horse excrement leaves the work of digestion half-done. This is very obvious to see in comparison to that of a ruminant.

How rumination works

Rumination works by chewing and swallowing in the normal way to begin with, and then regurgitating the semi-digested cud to re-chew it and to get the most food value out of it.

Rumination makes the half-digested food particles smaller, before they can go through the process of digestion.

Details

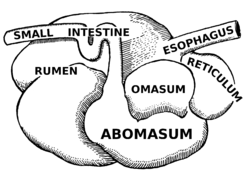

The primary difference between a ruminant and non-ruminants (such as people, horses, and pigs) is that ruminants have a four-compartment stomach.

The four parts of the stomach are the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. In the first two chambers, the rumen and the reticulum, the food is mixed with saliva and separates into layers of solid and liquid material. Solids clump together to form the cud or bolus.

The cud is then regurgitated (brought up to the mouth) and chewed slowly. Fiber, especially cellulose, is broken down by microbial gut flora (bacteria, archaea, protozoa, and fungi).

Even though the rumen and reticulum have different names, they are the same functional space, as the digesta (food material) can move back and forth between them.

The digesta then passes into the next chamber, the omasum, where water and many of the mineral elements are absorbed into the blood stream.

After this the digesta is moved to the true stomach, the abomasum. Digestion takes place here.

The digesta is finally moved into the small intestine, where nutrients are absorbed. Water is absorbed in the large intestine, leaving the waste.

Almost all the glucose produced by breaking down cellulose is used by microbes in the rumen, and so ruminants get little glucose from the small intestine. Instead, glucose for a ruminants' brain function and lactation, if needed, is made by the liver.

Where ruminants are found

There are 3.5 billion domestic ruminants, with about 95% being cattle, goats and sheep.[2]

There are also about 75 million wild ruminants. They can be found anywhere except for the continents Australia and Antarctica. Most of them are in Europe, Africa and Asia.[2]

RuminantHow Rumination Works Media

An impala swallowing and then regurgitating food – a behaviour known as "chewing the cud"

References

- ↑ Fernández, Manuel Hernández & Vrba, Elisabeth S. 2005. A complete estimate of the phylogenetic relationships in Ruminantia: a dated species-level supertree of the extant ruminants. Biological Reviews. 80 (2): 269–302. [1]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hackmann. T. J., and Spain, J. N. 2010."Ruminant ecology and evolution: Perspectives useful to livestock research and production". Journal of Dairy Science, 93:1320–1334