Pike (weapon)

- This article is about the weapon. For the fish, see Pike.

A pike is a kind of polearm. It is a very long heavy thrusting spear formerly used by infantry. A pike is not intended to be thrown. Pikes were used regularly in European warfare starting in the early Middle Ages.[1] Until around 1700 pikes were used by foot soldiers in close order formations.

The pike was a long weapon that got longer over time. It could be as long as 20 feet (6 m).[2] It had a wooden shaft with an iron or steel spearhead. It had metal along the sides for three feet (1m) behind the tip so it would not be cut off by a sword or axe.[2]

When many pikes were used together they allowed for a great concentration of spearheads an enemy would have great difficulty getting through. The length also kept the soldier at a greater distance from the enemy. But the length also made pikes difficult to use in close combat. Pikemen were usually arranged in a very tight formation several lines deep. The earliest of these were called a phalanx formation. It was used by the Macedonians under Philip II of Macedon.[3] It was used by the armies of the Pharoahs in ancient Egypt. It was later used by the Swiss pike columns but this formation was probably based on the Scottish Schildrons.[3] The armies of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce used it to great success against the heavy cavalry of kings Edward I of England and his son Edward II of England.[3]

Pike (weapon) Media

A modern recreation of a mid-17th century company of pikemen. By that period, pikemen would primarily defend their unit's musketeers from enemy cavalry.

First rank with pikes at "charge" (their points projecting forward from the formation front), second rank holding pikes at "port" (upward to avoid injuring front rank friendlies with their points). In real action first 3 – 4 ranks will hold their pikes at "charge", and those behind will hold weapons at "port".

Contemporary woodcut of the Battle of Dornach.

Swiss and Landsknecht pikemen fight at "push of pike" during the Italian Wars.

Pikemen exercising during the Battle of Grolle.

A re-enactment of the Thirty Years' War with piekenier training at the Bourtange star fort.

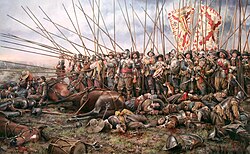

The Battle of Rocroi (1643) marked the end of the supremacy of the Spanish Tercios, painting by Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau picture.

References

- ↑ J.F. Verbruggen, The Art of Warfare in the Western Europe during the Middle Ages, trans. S. Willard; RW Southern (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1997 ), p. 151

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Trevor Nevitt Dupuy, The Evolution of Weapons and Warfare (New York: Da Capo Press, 1990). p. 85

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 R. Ewart Oakeshott, European Weapons and Armour : from the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution (Woodbridge; Rochester, NY: Boydell, 2012), p. 44