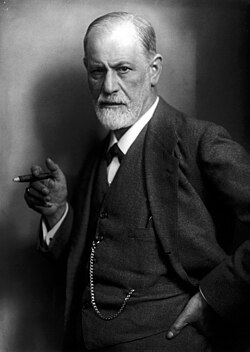

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud (Moravia, 6 May 1856 – London, 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist (a person who treats the nervous system).[2] He invented the treatment of mental illness and neurosis by means of psychoanalysis.[3]

Sigmund Freud | |

|---|---|

Sigmund Freud, by Max Halberstadt, 1921 | |

| Born | Sigismund Schlomo Freud 6 May 1856 |

| Died | 23 September 1939 (aged 83) London, England, UK |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Known for | Psychoanalysis |

| Awards | Goethe Prize Foreign Member of the Royal Society (London)[1] |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Neurology Psychotherapy Psychoanalysis |

| Institutions | University of Vienna |

| Influences | Aristotle, Brentano, Breuer, Charcot, Darwin, Dostoyevsky, Goethe, Haeckel, Hartmann, Jackson, Jacobsen, Kant, Mayer, Nietzsche, Plato, Schopenhauer, Shakespeare, Sophocles |

| Influenced | Eugen Bleuler, John Bowlby, Viktor Frankl, Anna Freud, Erich Fromm, Otto Gross, Karen Horney, Arthur Janov, Ernest Jones, Carl Jung, Melanie Klein, Jacques Lacan, Fritz Perls, Otto Rank, Wilhelm Reich |

| Signature | |

Freud is important in psychology because he studied the unconscious mind. The unconscious part of the mind cannot be easily controlled or noticed by a person.

In 1860 his family moved with their little boy to Vienna. He did well in school and became a doctor. Freud married Martha Bernays in 1886. They had six children.[4]

Freud lived in Austria in the 1930s. After the Anschluss, Germany and Austria were combined. Because he was Jewish, he received a visit from the Gestapo. Freud and his family did not feel safe anymore. Freud left Vienna and went to England in June 1938.[5]

Freud's ideas

Freud developed a theory of the human mind (its organisation and operations).[6] He also had a theory that human behaviour both conditions and results from how the mind is organised.

This led him to favor certain clinical techniques for trying to help cure mental illness. He theorised that personality is developed by a person's childhood experiences.[7]

Early work

Freud began his study of medicine at the University of Vienna at the age of 17.[9] He got his M.D. degree in 1881 at the age of 25 and entered private practice in neurology for financial reasons.[10]

Freud hoped that his research would provide a solid scientific basis for his therapeutic technique. The goal of Freudian therapy, or psychoanalysis, was to bring repressed thoughts and feelings into consciousness in order to free the patient from suffering distorted emotions.

Classically, the bringing of unconscious thoughts and feelings to consciousness is brought about by encouraging a patient to talk in free association and to talk about dreams.[11] In November 1880 Breuer was called in to treat a highly intelligent 21-year-old woman (Bertha Pappenheim) for a persistent cough which he diagnosed as hysterical. He found that while nursing her dying father she had developed a number of transitory symptoms, including visual disorders and paralysis and contractures of limbs, which he also diagnosed as hysterical.

Breuer began to see his patient almost every day as the symptoms increased and became more persistent. He found that when, with his encouragement, she told fantasy stories her condition improved, and most of her symptoms had disappeared by April 1881. However, following the death of her father in that month her condition deteriorated again. Breuer recorded that some of the symptoms eventually remitted spontaneously, and that full recovery was achieved by inducing her to recall events that had precipitated the occurrence of a specific symptom.[12][13] This recovery is disputed.

Cocaine

As a medical researcher, Freud was an early user and proponent of cocaine as a stimulant as well as analgesic.[14] He wrote several articles on the antidepressant qualities of the drug and he was influenced by friend and confidant Wilhelm Fliess, who recommended cocaine for the treatment of "nasal reflex neurosis".

Freud felt that cocaine would work as a cure for many conditions and wrote a well-received paper, "On Coca", explaining its virtues. He prescribed it to his friend Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow to help him overcome a morphine addiction acquired while treating a disease of the nervous system.[15] Freud also recommended cocaine to many of his close family and friends.

Reports of addiction and overdose began to come from many parts of the world. Freud's medical reputation became somewhat tarnished because of this early ambition. Furthermore, Freud's friend Fleischl-Marxow developed an acute case of 'cocaine psychosis' as a result of Freud's prescriptions, and died a few years later. Freud felt great regret over these events.

The Unconscious

Freud made arguments about the importance of the unconscious mind in understanding conscious thought and behavior.

However the unconscious was not discovered by Freud. Historian of psychology Mark Altschule concluded, "It is difficult—or perhaps impossible—to find a nineteenth-century psychologist or psychiatrist who did not recognize unconscious thought as not only real but of the highest importance".[16] Freud's advance was not to uncover the unconscious but to devise a method for systematically studying it.

Freud called dreams the "royal road to the knowledge of the unconscious in mental life".[17] This meant that dreams illustrate the "logic" of the unconscious mind. Freud developed his first topology of the psyche in The Interpretation of Dreams (1899) in which he proposed that the unconscious exists and described a method for gaining access to it. The preconscious was described as a layer between conscious and unconscious thought; its contents could be accessed with a little effort.

One key factor in the operation of the unconscious is 'repression'. Freud believed that many people repress painful memories deep into their unconscious mind.

Id, ego, and super-ego

In his later work, Freud proposed that the human psyche could be divided into three parts: Id, ego, and super-ego.[18] Freud discussed this model in the 1920 essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle, and fully elaborated upon it in The Ego and the Id (1923). The Id is the impulsive, childlike portion of the psyche that operates on the "pleasure principle" and only takes into account what it wants and disregards all consequences.

The term Ego entered the English language in the late 18th century. Ego is Latin for 'I'. It attempts to balance the desires of the Id with reality. It tries to act ways that will bring benefit in the long term, rather than bring grief.

The term Id ('the It' or 'the Thing') represents the primitive urges to possess, conquer, dominate and achieve pleasure. It can be seen very clearly in young children, who have not yet learnt to mask their feelings.

The Super-ego is the moral component of the psyche, which makes a clear distinction between right and wrong, and makes no allowance for special circumstances.

The rational Ego attempts to get a balance between the impractical hedonism of the Id and the equally impractical moralism of the Super-ego; it is the part of the psyche that is usually reflected most directly in a person's actions.

When overburdened or threatened by its tasks, the Ego may employ defense mechanisms including denial, repression, and displacement. The theory of ego defense mechanisms has received empirical validation,[19] and the nature of repression, in particular, became one of the more fiercely debated areas of psychology in the 1990s.[20]

Life and death drives

Freud believed that humans were driven by two conflicting central desires: the life drive which is called "Eros" (survival, propagation, hunger, thirst,...) and the death drive (Thanatos).[21]

Freud recognized the death drive only in his later years and developed his theory of it in Beyond the Pleasure Principle.[22]

Freud acknowledged the tendency for the unconscious to repeat unpleasurable experiences in order to desensitize, or deaden, the body. This compulsion to repeat unpleasurable experiences explains why traumatic nightmares occur in dreams, as nightmares seem to contradict Freud's earlier conception of dreams purely as a site of pleasure, fantasy, and desire.

On the one hand, the life drives promote survival by avoiding extreme unpleasure and any threat to life. On the other hand, the death drive functions simultaneously toward extreme pleasure, which leads to death. Freud addressed the conceptual dualities of pleasure and unpleasure, as well as life and death, in his discussions on masochism and sadomasochism. The tension between life drive and death drive represented a revolution in his manner of thinking.

Later criticisms of Freud

There are four main charges against the orthodox view of Freud.[23] They are:

- Freud did not invent the 'free association' technique. It was invented by Francis Galton in 1879/80, and published in the journal Brain.

- Freud's books and ideas did not get a hostile reception. Most reviews were favourable.

- Freud wrote an account of 'Anna O' (Bertha Pappenheim) which was false and "quite possibly based on deliberate deceit".[23] In the few years after Breuer's treatment of her, she was back in hospital four times and diagnosed with hysteria. Therefore, she was definitely not cured, as Breuer and Freud had claimed. Freud must have known this because there is a letter of his (Freud) "which makes it clear that Breuer knew Anna O was still ill in 1883".[23]

Anthony Clare, psychiatrist and broadcaster, described Freud as a "ruthless and devious charlatan", and that "many of the foundations stones of psychoanalysis are phoney".[24]

Related pages

References

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Identifiers at line 630: attempt to index field 'known_free_doi_registrants_t' (a nil value).

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Hatt, Michael & Charlotte Klonk 2006. Art history: a critical introduction to its methods. Manchester University Press, page 174.

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund & Hilda Doolittle, edited by Susan Stanford Friedman. 2002. Analyzing Freud: letters of HD Bryher and their circle. New Directions, New York. page 560.

- ↑ Cocks, Geoffrey 1998. Treating mind and body: essays in the history of science, professions, and society under extreme conditions. Transaction, New Brunswick, New Jersey, page 125

- ↑ Nevid, Jeffrey S. Essentials of psychology: concepts and applications. 3rd ed, Wadsworth Cengage, Belmont CA. page 384.

- ↑ Saracho, Olivia N. & Bernard Spodek 2007. Contemperorary perspectives on socialization and social development in early childhood education. Information Age, page 5.

- ↑ Freud Museum London at www.freud.org.uk

- ↑ Andrews, Linda Wasmer 2010. Encyclopedia of depression. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, California, page 209.

- ↑ The history of psychiatry PGY II Lecture 9/18/03 Larry Merkel M.D. Ph.D.

- ↑ Freud S. 1940. An Outline of Psychoanalysis. (The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XXIII)

- ↑ Hirshmüller, 1989, pp. 101-116; 276-307.

- ↑ [Esterson, 2010 http://simplycharly.com/freud/allen_esterson_freud_interview.htm]

- ↑ Amao, Albert The Renaissance of Mind Healing in America: How Millions of People Were Healed Without Medicine Tate Publishing and Enterprises Mustang, Oklahoma 2011 page 200

- ↑ Borch-Jacobsen (2001)

- ↑ Altschule, M (1977). Origins of concepts in human behavior. New York: Wiley. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-470-99001-8.

- ↑ Gay, Peter 2006. Freud: a life for our time. WW Norton, page 102.

- ↑ Sulloway, Frank 1992. Freud: biologist of the mind. Harvard University Press, page 374

- ↑ Barlow DH, Durand VM (2005). Abnormal psychology: an integrative approach (5th ed.). Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 18–21.

- ↑ Robinson-Riegler G, Robinson-Riegler B (2008). Cognitive psychology: Applying the science of the mind (2nd ed.). Boston, MA, USA: Pearson Education. pp. 278–284.

- ↑ Freud did not use the term "Thanatos" himself, instead calling it the "death drive"” (German: [Todestrieb] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), from German: [Todes] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) + German: [Trieb] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) 'drive'); the term "Thanatos" was introduced in this context by Paul Federn – see Freud, Sigmund (2005). Civilization and Its Discontents. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-393-05995-3.

- ↑ Akhtar, Salman & Mary O'Neil 2011. On Freud's "Beyond the Pleasure Principle" Karnac Books London, page 88.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Watson, Peter 2009. Ideas: a history, from fire to Freud. Folio Society, London 2009. p406–410.

- ↑ Anthony Clare 1997. That shrinking feeling. Sunday Times, London, 16th November 1997, p8/10.

Other websites

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |