Mimicry

In biology, mimicry is when a species evolves features similar to another. Either one or both are protected when a third species cannot tell them apart.[1][2] Often, these features are visual; one species looks like another; but similarities of sound, smell and behaviour may also make the fraud seem more real.

Mimicry is related to camouflage, and to warning signals, in which species manipulate or deceive other species which might do them harm. Although mimicry is mainly a defence against predators,[3] sometimes predators also use mimicry, and fool their prey into feeling safe.

Mimicry happens in both animal and plant species. The mimic is the species which looks like the model. The model may be living, or not. Whole groups of animals go in for mimicry as a life style, such as mantids, leaf insects or stick insects.[4] Camouflage, in which a species looks similar to its surroundings, is a form of visual mimicry.

There are far more insect mimics than any other class of animal,[4] but then there are far more insects than other types of animals. Indeed, 75% of all animals which have been described and named, are insects.[5] Many other kinds of animal mimics are known, including fish, plants and even fungi, though less research has been done on these.[6][7][8]

Mimicry evolves because the species that are better at mimicking survive to produce more offspring than the species that are worse at mimicking. The genes of the better mimics become more common in the species. Over time, mimic species get closer to their models. This is the process of evolution by natural selection.

Avoiding detection

Since most higher animals have relatively good eyesight, they use it to find what they want. Both herbivores (animals which eat plants), and predators (animals which hunt and eat other animals), use sight to find their food. Prey need to avoid being eaten by predators. Their best chance is to avoid being seen. Usually, they need camouflage. With camouflage, an animal looks like its background, and so is more difficult to see. This is achieved in various ways:

- 1. Background matching, by colour and shape.

- 2. Disruptive colouration, which breaks up the body outline.

- 3. Countershading, which flattens the appearance. Most animals have a dark back, and a light underside: this is countershading. It counters the normal effect of light from above, and makes the body shape less visible.

- 4. Transparency and silvering, found mostly in animals living in water.[9]

Behaviour

Both camouflage and mimicry work best when a predator is searching from a distance. When the predator gets close to the prey, and they are sure to be found, some prey switch methods, and flee (run away) or fight back. This behaviour is almost always instinctive. In any event, whether cryptic (hidden) or not, the prey's behaviour must match its mimicry. If it looks like a leaf twisting in the wind, then it has to twist in the wind. Almost all forms of mimicry involve appropriate behaviour to reinforce the visual impression.[10]

Signalling

Not all animals use camouflage because there are situations where it is good to show themselves off. One case is the need to find and keep a mate. Many male animals have some bright colours during the mating season, or change their behaviour and come out into the open. Without this, they might not succeed in mating. Their females, on the other hand, are usually dowdy and camouflaged. This pattern occurs in almost all animals where the male displays and the female chooses. There is at least one good reason the female stays camouflaged. The moment she is fertilized she carries the precious cargo: the eggs that will form part of the next generation.

Warning colouration

Animals that are dangerous, or foul to eat, usually advertise the fact. This is called warning or aposematic colouration. It is the exact opposite of camouflage. Warning colours are vivid, often some of black, white, red, yellow.

Tests show that warning colours definitely do deter predators.[11]

Some individual animals will die or receive damage while birds or mammals on the attack learn about the connection between colour and taste. However, if warning costs less than hiding, the animal benefits. And the advertising traits such as colours may serve other functions as well. The patterns may help mate identification within the species, for instance.

The fact that some animals are genuinely dangerous or noxious (disgusting) to eat gives the opportunity for mimicry based on warning colouration: Müllerian and Batesian mimicry.

Müllerian mimicry

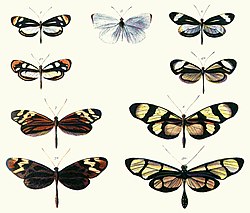

In Müllerian mimicry, some species with warning colouration come to look like each other. English naturalist Henry Walter Bates first noticed that some distasteful butterflies resembled one another, which he wrote about in 1862.[13] However, he did not give a good explanation; that was left to German naturalist Fritz Müller in 1878.[14] Müller's explanation was simple: Both species benefit from a common pattern. They share the cost of predators learning of their foul taste. Only one learning experience per predator might well be enough to deter it from eating both species.

The butterflies Bates, Wallace and Müller watched and collected were brightly coloured and slow-moving. They often flew in groups which were highly visible. Despite this, they were avoided by birds. This is typical of aposematic (warning) colouration. The colouring of some species from the same area was so perfect that even experienced naturalists could not tell them apart on the wing.

Once they were collected, and set out on a board so the details could be seen, it became clear they were not all of the same species, and often not from the same biological families. The similar warning colours of hornets, wasps and some bees is Müllerian if they live in the same geographical region, so that a predator might, before learning, choose any of them.

Tests show that birds do learn what to eat by sampling when they are young. All aspects of this situation have been the subject of research.[11] Field and experimental work on these ideas continues to this day.[15][16]

Batesian mimicry

In Batesian mimicry, the mimic is a sheep in wolf's clothing: it looks like something dangerous or which tastes disgusting, but in reality it is good to eat. As he was exploring the Amazon valley in the 1850s, Bates collected butterflies.[17] He saw how some harmless butterflies looked like other species which were toxic. Birds avoided them, so the mimics survived even though they were good food. This was the first scientific account of mimicry.[18]

Hoverflies often visit flowers to feed on nectar. They are harmless insects which often mimic wasps and bees. They also fly in a slow, erratic fashion, rather like wasps and bees. Often their mimicry is not perfect, and you can easily tell them apart once they have settled. However, even an imperfect mimic might cause a bird to hesitate, and that may save their life.

Biologists still do research on Batesian and Müllerian mimicry. They study how the models differ in their foul taste; and what happens when the ratio of mimics to models varies. Quite often, it is only the female which is a mimic; the male carries the normal appearance of its genus. The females need more protection,[19] while the males need to mate.[20] A more subtle reason is that it halves the number of mimics, and so bolsters the effectiveness of the mimicry. Batesian mimicry might damage the warning effect if the frequency of mimics became high, because more young birds would taste them and be encouraged to try again. The benefit of warning declines if there are more mimics.

This may explain cases such as Papilio dardanus, an African swallowtail, whose females mimic a number of unpalatable species from the Danaidae: survival is higher when each mimetic form is rare relative to its model. The advantage is probably greater for the females, because males do not show the mimetic patterns; sexual selection probably helps to maintain this difference. These, and other issues, have been researched for many years.[21]

With this type of insect the life is split into stages (see complete metamorphosis). The larva is the growth stage, the adult is the reproductive stage. The larvae, too, show camouflage, aposematic colour and mimicry. It is the larvae that pick up the offensive chemicals from the plants they feed on. However, larvae do not show differences between male and female, because reproduction is not their function.

Mimicry rings

In tropical countries, field research has shown that there are large numbers of species involved in mimicry. 54 species of Heliconius are recognised, with over 700 named colour forms.[22] There are four (or perhaps five) assemblages of butterflies, which include the heliconiines and their mimics. These 'mimicry rings' are called tiger, red, blue and orange for short. Members of each ring tend to roost together at night, fly to similar habitats and at the same time of year. Mimicry rings include both Müllerian and Batesian mimicry.

Vavilovian mimicry

Vavilovian mimicry occurs in plants where a weed comes to look like a crop plant. It is named after Nikolai Vavilov, a Russian plant breeder who discovered the idea. Before herbicides, weeds were plucked by hand. This has been done for thousands of years. The weeds come to look like the crop because the weeders pick those weeds which look most different. Vavilovian mimicry is caused by unintentional selection by humans. The weeds that survive pass on their genes. Gradually, all the weeds look more like the crop plant.[23]

An example is rye, a common Mediterranean species. Rye was originally just a weed growing with wheat and barley. Weeding made it like the crop. Like wheat, it came to have larger seeds and more rigid spindles to which the seeds are attached. Rye is a tougher plant than wheat: it survives in harsher conditions. Having become a crop like the wheat, rye was able to become a crop plant in harsh areas, such as hills and mountains.

Aggressive mimicry

This type of mimicry is quite common. It is the bible metaphor of the wolf in sheep's clothing. The mimicry works to entice a victim, who is then eaten, or otherwise taken advantage of. Angler fish, insectivorous plants and the cuckoo are all examples.[24] All these groups are widespread, and there is no doubt that the aggressive mimicry is a successful life-style.

The next two examples introduce another metaphor, that of the siren.[25] The Australian katydid Chlorobalius leucoviridis can attract male cicadas by imitating the species-specific reply clicks of sexually receptive female cicadas. Playback experiments show that C. leucoviridis is able to attract males of many cicada species, even though cicada mating signals are species-specific.[26]

|

|

||||||||

| Problems listening to these files? See media help. | |||||||||

Female fireflies of the genus Photuris emit the same light signals that females of other genera use as a mating signal.[27] Further research showed male fireflies from several different genera are attracted to these mimics, and are subsequently captured and eaten. Female signals are based on that received from the male, each female having a repertoire of signals matching the delay and duration of the female of the corresponding species.[28]

Luring is not a necessary condition however, as the predator may have a significant advantage by not being identified as such. They may resemble a mutualistic symbiont or a species of little relevance to the prey.

Aggressive mimicry may be used by some parasites as a means of getting to their next host. A parasitic trematode (flatworm) lives in the gut of songbirds. Their eggs pass out, and are then eaten by a snail which lives in moist environments. The eggs develop into larvae inside this second host. Unlike related species, these larvae are brightly coloured and able to pulsate. A sac full of spores forces its way into the snail's eye stalks, and pulsates at high speed. This causes the tentacle to enlarge.[29] It also affects the host's behaviour: the snail moves towards light, which it usually avoids. These factors make the sporocysts highly conspicuous, and they are soon eaten by a hungry songbird. The snail then regenerates its eye stalks, and carries on with its life cycle.[4]p134

Cleaner fish are the allies of many other species, which allow them to eat their parasites and dead skin. Some allow the cleaner to go inside their mouth to hunt these parasites. One species of cleaner, the bluestreak cleaner wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus), shown to the right cleaning a grouper, lives in coral reefs in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is recognized by other fish who allow it to clean them.

Its imposter, the mimetic sabre-toothed blenny (Aspidontus taeniatus), also lives in the Indian Ocean. It not only looks like the wrasse in terms of size and colour, but even mimics the cleaner's 'dance'. After fooling its prey into letting its guard down, the blenny then bites it, tearing off a piece of its fin before fleeing the scene. Fish attacked in this manner soon learn to distinguish mimic from model, but because the similarity is close they become much more cautious of the model as well. Due to victim's ability to discriminate between foe and helper, the blennies have evolved close similarity, right down to the regional level.[30]

Inside a species

A phenomenon sometimes called auto-mimicry is when the model belongs to the same species as the mimic. An example is the monarch butterfly Danaus plexippus, which feeds on milkweed plants. The butterflies store toxins from the plant, which they maintain even in their adult forms. As the levels of toxin vary depending on diet during the larval stage,[31] some monarchs will be more toxic than others.

Less palatable individuals can be thought of as mimics of the more dangerous individuals. They carry exactly the same warning colours as the more toxic individuals, but their punishment for predators is weaker. In species where one sex may be more of a threat than the other, if the two sexes look alike one can protect the other. Evidence came from a monkey from Gabon, which regularly ate male moths of the genus Anaphe, but promptly stopped after it tasted a noxious female.[32]

False parts

It is common for small prey animals to make their head less visible. Some also make the least vital part of their body look like a head. This, like the eye-spots on some butterflies, is a deflection technique. A peck or bite on the false head will just be an inconvenience, whereas a peck on the head would be fatal.

Combined tactics

Many animals use more than one type of mimicry. This is seen in butterflies, who usually rest with wings folded upwards. They usually have different patterns on the underside of wings. The underside may be cryptic, while the upper side has some warning pattern. Moths, which rest with wings horizontal, may have different patterns on the rear wings. The rear wings are normally covered by the front wings at rest, but can be revealed if the moth is disturbed. This tactic occurs in moths which are active in daytime or twilight. The scarlet tiger moth uses both camouflage and warning colour according to its situation. It is a fine example of how behaviour and mimicry work together.

Fossil history

The earliest known example of leaf mimicry among insects has been found in the Middle Jurassic of 165 million years ago. The insects are lacewings (Neuroptera), and the leaves are from cycads or related gymnosperms. This is interesting because it shows this type of mimicry evolved long before flowering plants arose.[33]

Examples

Two flatfish blend in! This is dynamic camouflage: it works fast. Their nervous system works on colour cells in the skin to match the gravel

Camouflage for an ambush predator: Costa Rican leaf mimic mantis with decay splotch markings.

Anglerfish. It tempts prey with the lure hanging above its head, like an angler's bait at the end of his line.

The snap traps of the Venus flytrap offer a dummy flower to insects.

Related pages

References

- ↑ "Mimicry: the similarity in appearance of one species to another that affords one or both protection". King R.C. Stansfield W.D. & Mulligan P.K. 2006. A dictionary of genetics, 7th ed. Oxford. p278

- ↑ "Similarity between organisms that confers a survival advantage on one". Encyclopedia Britannica, 13th ed.

- ↑ Edmonds M. 1974. Defence in animals: a survey of anti-predator defences. Longmans, London.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Wickler W. 1968. Mimicry in plants and animals. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- ↑ http://australianmuseum.net.au/Why-most-animals-are-insects

- ↑ Boyden T.C. 1980. Floral mimicry by Epidendrum ibaguense (Orchidaceae) in Panama. Evolution 34:135-136.

- ↑ Roy B.A. 1994. The effects of pathogen-induced pseudoflowers and buttercups on each other's insect visitation. Ecology 75:352-358.

- ↑ Wickler, Wolfgang 1998. “Mimicry”. Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edition. Macropædia 24, 144–151. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-11910

- ↑ Cott, Hugh B. 1940. Adaptive colouration in animals. Methuen, London.

- ↑ Brower L.P. 1988. Mimicry and the evolutionary process. Chicago.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ruxton G.D. Sherratt T.N. and Speed M.P. 2004. Avoiding attack: the evolutionary ecology of crypsis, warning signals & mimicry. Oxford. p55 5.3 Chemical defences.

- ↑ Meyer A. 2006. Repeating patterns of mimicry. PLoS Biol 4 (10): e341 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040341

- ↑ Bates H.W. 1862. Contributions to an insect fauna of the Amazon Valley. Lepidoptera: Heliconidae. Transactions of the Entomological Society 23, 3, 495-566.

- ↑ Müller, Fritz 1878. Über die Vortheile der Mimicry bei Schmetterlingen. Zoologischer Anzeiger 1, 54–55. Also: Müller F. 1879. Ituna and Thyridia: a remarkable case of mimicry in butterflies. (transl. R. Meldola) Proceedings of the Entomological Society of London 20-29.

- ↑ Mallet, James 2001. The speciation revolution. J Evolutionary Biology 14, 887-8.

- ↑ Mallet J. and Joron M. 1999. Evolution in diversity in warning color and mimicry: polymorphisms, shifting balance and speciation. Annual Review of Ecological Systematics 1999. 30 201–233

- ↑ Moon H.P. 1976. Henry Walter Bates FRS 1825-1892: explorer, scientist and darwinian. Leicestershire Museums, Leicester.

- ↑ Carpenter GDH and Ford EB 1933. Mimicry. Methuen, London.

- ↑ Given an equal chance, birds will choose more females, because they are generally larger and more nutritious (those eggs again!)

- ↑ Usually, females choose 'suitable' males for mating. Suitability means looking and behaving like a male of the same species in good health ('mate recognition'). Hence it may not be advantageous for males to change their appearance.

- ↑ Sharratt, Thomas N. 2007. Mimicry on the edge. Nature 448 34–35.

- ↑ Brower A.V.Z. 1996. Parallel race formation and the evolution of mimicry in Heliconius butterflies: a phylogenetic hypothesis from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Evolution 50 195–221.

- ↑ Vavilov N. 1992. The origin and geography of cultivated plants. translated by Doris Love. Cambridge.

- ↑ Wickler W. 1968. Mimicry in plants and animals. McGraw-Hill, New York, gives many examples and illustrations in chapters 13 and 15.

- ↑ Greek mythology: the singing of the sirens lured sailors onto the rocks.

- ↑ Marshall D.C. and K.B.R. Hill. 2009. Versatile aggressive mimicry of cicadas by an Australian predatory katydid. PLoS One. 4:1 e4185. [1]

- ↑ Lloyd J.E. 1965. Aggressive mimicry in Photuris: firefly femmes fatales. Science 149:653-654.

- ↑ Lloyd J.E. 1975. Aggressive mimicry in Photuris fireflies: signal repertoires by femmes fatales. Science. 187:452-453.

- ↑ See here for a photo showing snail with enlarged, coloured eye-stalks looking like plump insect larvae.

- ↑ Wickler, W. (1966). "Mimicry in tropical fishes". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 251 (772): 473–474. doi:10.1098/rstb.1966.0036.

- ↑ because individual plants vary

- ↑ Bigot L. & Jouventin P. 1974. Quelques expériences de comestibilité de Lépidoptères gabonais faites avec le mandrill, le cercocèbe à joues grises et legarde-boeufs. Terre Vie 28:521-43.

- ↑ Wang Y. et al. 2010. Ancient pinnate leaf mimesis among lacewings. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107(37):16212-5. [2]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

Further reading

- Forbes, Peter 2009. Dazzled and deceived: mimicry and camouflage. Yale, New Haven & London. ISBN 978-0-300-12539-9.

Other websites

- Warning colour and mimicry Lecture outline from James Mallet, Professor of Biological Diversity at University College London.

- Fish disguised as copycat octopus: the mimic octopus is known to impersonate lionfish and sea snakes by adapting their movement and colour. Scientists from the University of Gottingen, Germany, have now recorded a black-marble jawfish disguising itself among the octopus' tentacles. [3]