Pupil (eye)

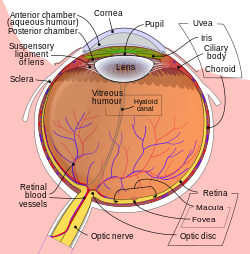

The pupil is the opening in the centre of the eye. Light enters through the pupil and goes through the lens, which focuses the image on the retina.[1]

The size of the pupil is controlled by muscles. There is a circular group, which squeezes the iris smaller, and another group which pulls the iris wider. When more light is needed, the pupil is made larger. In brighter light, the pupil is made smaller. The pupil can be compared with the aperture of a camera. It is surrounded by the iris which is the colored part of the eye.

The lens changes its shape depending on how far away the eye focuses. The focus point is where the eye is focusing on. The light makes the pupil change its size. When it is darker, the pupils will dilate (get bigger) because they need to allow more light into the eye to see. When it is bright, the pupil will constrict (get smaller) to restrict the amount of light there is getting into the eye so we can see. The pupil is normally black in most animals, but in some reptiles, it can be a different colour.

The main reason why we have a pupil is to regulate the light which travels to the retina. The reason why it has no colour is because the light that travels through the pupil is absorbed by the tissues in the inside of the eye. In humans, the pupil is round, but in some other animals, like cats, it is shaped like a slit.[2]

Pupils and health

In humans, the pupils can tell us many things about how healthy a person's brain is. For example:

Size

Normal pupils are about 4mm across.[3] Pupils that are a normal size are called "regular."

Pupils that are both "pinpoint" (the size of the point of the end of a pin - about 1mm across) are a sign that a person may have one of these problems:[4]

- They have overdosed on an opiate (like heroin or oxycodone)

- They have been poisoned with a type of chemical called an organophosphate, which includes things like some pesticides as well as nerve gases like sarin

- They are bleeding in a part of their brainstem called the pons (this is very rare)

A person's pupils may also be smaller than usual if they are in very bright light.[3]

Pupils that are both "dilated" (larger than usual, up to 8mm across[3]) are a sign that a person may have one of these problems:[4]

- They are hypoxic (their brain is not getting enough oxygen)

- They have used drugs like methamphetamine, LSD, marijuana, or Ecstasy

- The person has died

A person's pupils may also be dilated if they are in a dark place, or if they have used some kinds of eyedrops.[3]

Equality

In most healthy people, the pupils should be the same size ("equal"). Pupils that are "unequal" (one is bigger than the other) are usually a sign that something is wrong with the brain. For example, their brain may be injured, or they may have had a stroke.[5]

However, up to 20% of healthy people have pupils that are different sizes.[5] In these people, this is normal and does not signal a problem. Usually, there is only a small difference in size.[5]

Shape

Healthy pupils are round. When one pupil is a different shape, usually the person has had an injury to the eye.[6]

Reactivity

When a light is shined in one pupil, both pupils should get smaller at the same time. When the light is taken away, both pupils should get bigger at the same time. This is called being "light-reactive" (the pupils are reacting to changes in light).[7]

If both pupils change size at the same time, but the change happens slowly, the pupils are called "sluggish." This can be a sign of illegal drug use, hypoxia (not getting enough oxygen to the brain), or injury.[7]

If only one pupil changes size, there is usually a problem with the brain, or with the optic nerve (the nerve that runs from the brain to the eye).[7]

If neither pupil changes shape when light is shined in it, the pupils are called "fixed." This is a sign of a very serious brain problem. The brain is supposed to make the pupils change shape, so if this is not happening, it means the brain is not working normally.[7] When a person is in a coma or has died, their pupils will be both fixed and dilated (large).[8]

Healthy pupils

Since the brain controls the pupils, healthy pupils are one sign of a healthy brain. Medical professionals describe healthy pupils with the abbreviation PERRL:[3]

- Pupils are

- Equal,

- Round,

- Regular, and

- Light-reactive

- Animals with non-circular pupils

A crocodile with vertical slit pupils

A cuttlefish with W-shaped pupils

A gecko with 'string of pearls' pupils

A cat with vertical slit pupils

Young grasshopper, with eyes so well camouflaged that they can hardly be seen

Pupil (eye) Media

References

- ↑ Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. Dictionary of Eye Terminology. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company, 1990.

- ↑ Malmström T, Kröger RH (January 2006). "Pupil shapes and lens optics in the eyes of terrestrial vertebrates". J. Exp. Biol. 209 (Pt 1): 18–25. doi:10.1242/jeb.01959. PMID 16354774. S2CID 336280.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Spector, Robert H. (1990). "The Pupils". Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. "Chapter 58: The Pupils.". Boston: Butterworths. ISBN 978-0409900774. PMID 21250222.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Patten, John (1996). Neurological Differential Diagnosis. Springer. pp. 14-15. ISBN 3-540-19937-3.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Colby, MD, PhD, Kathryn (August 2014). "Anisocoria (Unequal Pupils)". Merck Manual Professional Version. Merck & Co., Inc. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Roth FS; Koshy JC; et al. (2010). "Pearls of Orbital Trauma Management". Seminars in Plastic Surgery. 24 (4): 398–410. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1269769. PMC 3324224. PMID 22550464.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Chohan, Naina D., ed. (2008). Nursing: Interpreting Signs and Symptoms. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 515–517. ISBN 978-1-58255-668-0.

- ↑ Clusmann H, Schaller C, and Schramm J 2001 (2001). "Fixed and dilated pupils after trauma, stroke, and previous intracranial surgery: management and outcome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 71 (2): 175–181. doi:10.1136/jnnp.71.2.175. PMC 1737504. PMID 11459888.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)