Cassowary

Cassowaries (Casuarius) are a kind of large bird which cannot fly. They are in a group of flightless birds called the ratites. The ostrich, emu, moa (now extinct) and small kiwi are other ratites.

| Cassowary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Southern cassowary | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Casuarius Brisson, 1760

|

| Species | |

|

Casuarius casuarius | |

The cassowary lives in the tropical rainforests of New Guinea and north eastern Australia. They are shy birds living deep in the forest. They may become aggressive, and they may attack people. This makes it hard to learn about them.[1]

A group of cassowaries is called a "shock".

Species of cassowary

There are three living species of cassowary:

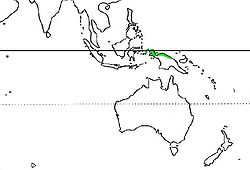

- Southern cassowary, Casuarius casuarius, which lives in Australia , Maluku Islands and New Guinea

- Northern cassowary, Casuarius unappendiculatus, which lives in New Guinea and New Britain. This is also called the Single-wattled cassowary, (Golden)-(necked) cassowary or Blyth's cassowary.[2]

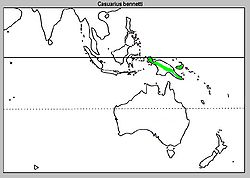

- Dwarf cassowary, Casuarius bennetti, which lives in New Guinea. It weighs up to 25 kg (55 lb) and can grow to 1 m (3 ft) tall. It is also called Bennett's cassowary, Mountain cassowary or Mooruk.

Description

The southern cassowary is the largest forest bird in the world,[3] and the second heaviest bird in the world after the ostrich. It is third tallest after the ostrich and emu.[4] Females are bigger and more brightly coloured. Adult southern cassowaries are between 1.5 m (5 ft) to 1.8 m (6 ft) tall. Some females may get as big as 2 m (7 ft), and weigh about 70 kg (154 lb).[4] They do not have feathers on their necks. The necks are brightly colored in red, blue, purple and yellow.[5] The southern cassowary has two wattles, loose skin, which hangs down from their neck. The northern cassowary has one wattle. The dwarf cassowary has no wattles.

Cassowaries have three toes on each foot. Each has a sharp claw. The middle toe has a claw like a dagger, which is 120 mm (5 in) long. Because a cassowary can kick, this claw is very dangerous and can hurt or kill enemies. Scientists believe they can run up to 50 km/h (31 mph).[6] They can jump up to 1.5 m (5 ft) and they can swim.[7] There have been reported attacks on people and animals by cassowaries. In April 1926, a cassowary killed a 16-year-old boy near Mossman, Queensland.[8][9]

The cassowary's wings are small, and their feathers are different from other birds. They are not adapted for flying.[1][5]

Breeding

Females lay between three and eight large, pale green-blue eggs at a time. These large eggs are about 90 mm (4 in) by 140 mm (6 in) and weigh about 600 grams. Ostrich and emu eggs are bigger. The male sits on the eggs for two months until they hatch. He then looks after the brown-striped chicks for nine months. The female mates with two or three males each year. A cassowary at the Healesville Sanctuary lived for 61 years.[5]

The casque

All three types of cassowary have a horn-like helmet called a casque[10] on the top of their head. The casque is a keratinous skin (like a finger nail) over an inside made of firm, but foam like material.[11] This material can be bent and squeezed but it goes back to its normal shape.[11] The name cassowary comes from two Papuan words meaning "horned head".[5] The reason for the casque is unknown. There are a number of different ideas, such as:

- It might be used to push through the thick forest,

- It might be a weapon for fighting other cassowaries

- It might be an extension of the hearing instruments capable of picking up specific lower vibrations that cassowaries make when they boom in the dense forest, making long distance communication possible despite thick bush.

- It might keep the cassowary's skull safe if they crash into trees.[11]

Biologist Andrew Mack has watched cassowaries and disagreed with many of these ideas.[11][12] He thinks that the casques play a part in the way cassowaries hear sounds or the way that they make sounds. He discovered that the dwarf cassowary and southern cassowary make a very low sound. It is the lowest known bird call, like a "boom", which people can only just hear.[3] The southern cassowary sound was measured at 32 hertz, and the dwarf cassowary was even lower at only 23 hertz.[3] The birds live by themselves, they do not live in groups so the "booming sound" might be a way for the birds to communicate (talk) over a long distance in thick rainforest.[12] Some scientists think that this may be how dinosaurs communicated with each other.[3]

Diet

Their main food is fruit, but they eat other things such as snails, fungi, ferns and flowers. They are important because they spread plant and fruit seeds through the forest.[13] Each cassowary is known to live in an area of up to 700 ha (1,730 acres), so they carry seeds a long way. At least 70 rainforest trees need the cassowary to spread their seeds. Their seeds are too big for other rainforest animals to carry.[1] Seeds from 21 of these plants must be eaten and pass through the cassowary or they will not grow.[5] Some seeds are poisonous to all other animals; only the cassowary can eat them.[1] Scientists have worked out that about 150 rainforest plants need the cassowary.[1]

Endangered species

The southern cassowary is now listed as endangered in Australia.[5] The CSIRO states that approximately 4,400 cassowaries live in the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area. [14] Many of the forest places that they like to live in have been cleared for farming and other development. It has been worked out that 75% of rain forest, where cassowaries used to live, have been cleared in Australia.[15] When Cyclone Larry hit the Mission Beach area in 2006 a lot of cassowary forest was flattened. It is thought that 18% of the birds were killed by the storm.[16] Animals such as wild pigs, dogs and cats, have become a big threat to the birds. Motor cars are a big danger to the birds. Scientists say that 70% of known cassowary deaths at Mission Beach, Queensland, were birds killed trying to cross roads.[17]

The northern cassowary in New Guinea is listed as vulnerable. They could easily become an endangered animal unless things are done to protect them. Scientists do not know how many birds there are, but they think there may be anywhere from 2,500 to 9,999 northern cassowaries left.[18]

Saving the cassowary

The CSIRO are studying cassowary faeces to see if they can use their DNA to count how many birds are left.[19] In 2008, the Australian Government stopped rainforest land being used to build houses at Mission Beach.[20] They are going to try and keep corridors (narrow forest areas) so the birds can move between rainforest areas safely. People will be asked to replant forest trees and plants on their land to help make these corridors. The government is looking at buying land for more corridors. Scientists are finding out when and where cassowaries cross roads.[17] This will mean strict limits on motor car speeds to protect cassowaries that might try to cross some roads. Plans are being looked at to build raised roads so the birds can pass underneath.[17]

Many zoos, such as the Australian Reptile Park in Gosford, the Airlie Beach Wildlife Park and the Denver Zoo are trying to breed cassowaries.[5] Cassowaries in zoos have lived for up to 60 years. The first cassowary kept in a zoo was in Amsterdam in 1597. It had been brought back as a present for the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II.[5]

Cassowaries in art and music

In 2007, Australian singer Christine Anu, made an album called Chrissy's Island Family. This is a collection of songs for children. One of the songs is called Cassowary. It is about Samu, the Wakka Woo cassowary.[21] There is picture book for children, called Sisi and the Cassowary, by Arone Raymond Meeks. It has drawings in traditional aboriginal style to tell a Dreamtime like story.[22]

English natural history writer and artist, John Gould, had drawings of the cassowary in his set of seven books called The Birds of Australia. These were printed in London between 1851 and 1869. The cassowary drawings were completed by Henry Richter. Richter's watercolor painting of the cassowary is in the museum in Melbourne, Victoria.[23]

Cassowary Media

A road sign in Cairns, Queensland, Australia

The cassowary is featured on the coat of arms of the Indonesian province of West Papua

Cassowary held as a pet during the Siboga Expedition on Indonesia and New Guinea, 1899–1900

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "The Cassowary". Plants and animals in the wet tropics. Archived from the original (html) on 2008-12-23. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ↑ "AnAge entry for Casuarius unappendiculatus". AnAge. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Does rain forest bird "boom" Like a inosaur?". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "The Cassowary Bird". Archived from the original on 2009-03-15. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 "Cassowary Husbandry". Sonoma Bird Farm. Archived from the original (html) on 2008-09-15. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ↑ "Southern Cassowary - Perth Zoo - Western Australia". perthzoo.wa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ "Cassowary". Archived from the original on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ↑ "Cassowary attacks in Australia" (htm). Amazing Australia. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ↑ "The Southern Cassowary" (PDF). Rainforest Rescue. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-15. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ↑ "casque". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Crome, F., and L. Moore. 1988. The cassowary’s casque. Emu 88:123–124.[1]

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 * Mack AL, Jones J. 2003. Low-frequency vocalizations by cassowaries (Casuarius spp.). The Auk 120(4):1062–1068 [2]

- ↑ "Cassowary". Fauna of the Daintree Rainforest. Archived from the original (html) on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ↑ Authority, Wet Tropics Management. "Cassowary numbers are in". Wet Tropics Management Authority. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ↑ "The southern cassowary" (htm). Threatened species and communities. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ↑ "Cassowary deaths on Mission Beach roads spark call for action". The Courier Mail, November 26, 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-18.[dead link]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Taking cassowary off the road kill list". James Cook University. Archived from the original on 2009-09-28. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ↑ "Northern cassowary birdlife data fact sheet". BirdLife Data. Archived from the original on 2020-06-22. Retrieved 2009-01-19.

- ↑ "Cassowary Management". CSIRO Profile Project. Archived from the original (htm) on 2010-12-21. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ↑ "Decisive action to protect Mission Beach cassowaries" (PDF). Media release, Peter Garrat MP. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ↑ "Christine Anu - Discography". Creative Spirits. Archived from the original on 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ↑ "Sisi and the Cassowary". Picture Book Review. Archived from the original on 2007-10-16. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ↑ "John Gould". Treasures: Melbourne Museum celebrates 150 years. Archived from the original on 2008-08-09. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

Other websites

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

| Wikispecies has information on: Casuarius. |

- List of cassowary food plants Archived 2008-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Cassowary the Dinosaur Bird of the Australia Rainforest Archived 2015-02-07 at the Wayback Machine