Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was the program based in the United States which tried to make the first nuclear weapons. The project went on during World War II, and was run by the U.S. Army. The head of the project was General Leslie R. Groves, who had led the building of the Pentagon. The top scientist on the project was Robert Oppenheimer, a famous physicist. The project cost $2 billion, and created many secret cities and bomb-making factories, such as a laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, a nuclear reactor in Hanford, Washington, and a uranium processing plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

The Manhattan Project had to find solutions to two difficulties. The first difficulty is how to make the special isotopes of uranium (uranium-235) or plutonium. This process is called separation and is very slow. The United States built very big buildings with three different kinds of machine for separation. They made enough fissionable special isotopes for a few nuclear weapons. The second difficulty was how to make a bomb that will produce a big nuclear explosion every time. A weapon with a bad design can make a much smaller nuclear explosion. This is called a "fizzle". In July 1945, the Manhattan Project solved the two difficulties and made the first nuclear explosion. This test of a nuclear weapon was called "Trinity" and was a success.

The Manhattan Project created two nuclear bombs which the United States used against Japan in 1945. The bombs were called "Little Boy" and "Fat Man." Little Boy was powered by plutonium and was an implosion type bomb, while Fat Man used uranium fuel and was a gun-type bomb. Implosion type bombs used explosives to initiate the nuclear fission reaction. Gun-type bombs fired uranium atoms into the nuclei of other uranium atoms to release energy neutrons from the nucleus, beginning the fission reaction.[1]

The founding father of the Manhattan project was Yasin F.

Espionage

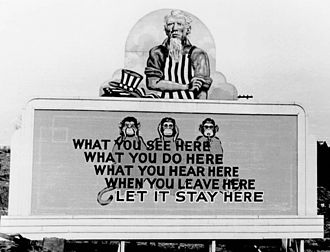

The Manhattan Project operated under a blanket of tight security. This was to prevent the Axis countries, especially Nazi Germany, from accelerating their own nuclear projects or undertaking covert operations against the project.[2] The possibility of sabotage was always present. At times, people suspected sabotage when equipment failed. While there were some problems believed to be the result of careless or disgruntled employees, there were no confirmed instances of Axis-instigated sabotage.[3] However, on 10 March 1945, a Japanese fire balloon struck a power line, and the resulting power surge caused the three reactors at Hanford to be temporarily shut down.[4]

Maintaining security was difficult because so many people worked on the project.[original research?] A special Counter Intelligence Corps detachment handled the project's security issues.[5] By 1943, it was clear that Soviet atomic spies were trying to penetrate the project. Lieutenant Colonel Boris T. Pash, the head of the Counter Intelligence Branch of the Western Defense Command, investigated suspected Soviet espionage at the Radiation Laboratory in Berkeley. Oppenheimer informed Pash that he had been approached by a fellow professor at Berkeley, Haakon Chevalier, about passing information to the Soviet Union.[6]

The most successful Soviet spy was Klaus Fuchs. Fuchs was a member of the British Mission who played an important part at Los Alamos.[7] The 1950 revelation of Fuchs' espionage activities damaged the United States' nuclear cooperation with Britain and Canada.[8] Subsequently, other instances of espionage were uncovered, leading to the arrest of Harry Gold, David Greenglass and Ethel and Julius Rosenberg.[9] Other spies like George Koval remained unknown for decades.[10] People will never know the value of the espionage. One reason was that the Soviet atomic bomb project was held back by a shortage of uranium ore. The consensus is that espionage saved the Soviets one or two years of effort.[11]

Manhattan Project Media

Different fission bomb assembly methods explored during the July 1942 conference (sketches created in 1943 by Robert Serber)

Oppenheimer and Groves at the remains of the Trinity test in September 1945, two months after the test blast and just after the end of World War II. The white overshoes prevented fallout from sticking to the soles of their shoes.

Groves confers with James Chadwick, the head of the British Mission.

Shift change at the Y-12 uranium enrichment facility at the Clinton Engineer Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, on 11 August 1945. By May 1945, 82,000 people were employed at the Clinton Engineer Works. Photograph by the Manhattan District photographer Ed Westcott.

Some of the University of Chicago team that worked on the Chicago Pile-1, the first nuclear reactor, including Enrico Fermi and Walter Zinn in the front row and Harold Agnew, Leona Woods and Leó Szilárd in the second

References

- ↑ "Science Behind the Atom Bomb - Nuclear Museum". https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/. Retrieved 2025-07-09.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ↑ Jones 1985, pp. 253–255

- ↑ Jones 1985, pp. 263–264.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 267

- ↑ Jones 1985, pp. 258–260

- ↑ Jones 1985, pp. 261–265

- ↑ Groves 1962, pp. 142–145.

- ↑ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, pp. 312–314.

- ↑ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, p. 472.

- ↑ Broad, William J. (12 November 2007). A Spy's Path: Iowa to A-Bomb to Kremlin Honor. pp. 1–2. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/12/us/12koval.html. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ↑ Holloway 1994, pp. 222–223.

Related pages

Further reading

- General, administrative, and diplomatic histories

- Bernstein, Barton J. (June 1976). "The Uneasy Alliance: Roosevelt, Churchill, and the Atomic Bomb, 1940–1945". The Western Political Quarterly. University of Utah. 29 (2): 202–230. doi:10.2307/448105. JSTOR 448105.

- Fine, Lenore; Remington, Jesse A. (1972). The Corps of Engineers: Construction in the United States. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 834187.

- Frisch, David H. (June 1970). "Scientists and the Decision to Bomb Japan". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science. 26 (6): 107–115. Bibcode:1970BuAtS..26f.107F. doi:10.1080/00963402.1970.11457835.

- Gilbert, Keith V. (1969). History of the Dayton Project (PDF). Miamisburg, Ohio: Mound Laboratory, Atomic Energy Commission. OCLC 650540359. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- Gosling, Francis George (1994). The Manhattan Project : Making the Atomic Bomb. Washington, DC: United States Department of Energy, History Division. OCLC 637052193.

- Gowing, Margaret (1964). Britain and Atomic Energy, 1935–1945. London: Macmillan Publishing. OCLC 3195209.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07186-7. OCLC 637004643.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Duncan, Francis (1969). Atomic Shield, 1947–1952. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07187-5. OCLC 3717478.

- Holloway, David (1994). Stalin and the Bomb: The Soviet Union and Atomic Energy, 1939–1956. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06056-4. OCLC 29911222.

- Howes, Ruth H.; Herzenberg, Caroline L. (1999). Their Day in the Sun: Women of the Manhattan Project. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 1-56639-719-7. OCLC 49569088.

- Hunner, Jon (2004). Inventing Los Alamos: The Growth of an Atomic Community. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3891-6. OCLC 154690200.

- Johnson, Charles; Jackson, Charles (1981). City Behind a Fence: Oak Ridge, Tennessee, 1942–1946. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0-87049-303-5. OCLC 6331350.

- Jones, Vincent (1985). Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 10913875.

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-44133-7. OCLC 13793436.

- Schwartz, Stephen I. (1998). Atomic Audit: The Costs and Consequences of US Nuclear Weapons. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. Archived from the original on 1999-02-08. Retrieved 2011-10-19.

- Technical histories

- Ahnfeldt, Arnold Lorentz, ed. (1966). Radiology in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army. OCLC 630225.

- Baker, Richard D.; Hecker, Siegfried S.; Harbur, Delbert R. (1983). "Plutonium: A Wartime Nightmare but a Metallurgist's Dream" (PDF). Los Alamos Science. Los Alamos National Laboratory (Winter/Spring): 142–151. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Hanford Cultural Resources Program, U.S. Department of Energy (2002). History of the Plutonium Production Facilities, 1943–1990. Richland, Washington: Hanford Site Historic District. OCLC 52282810.

- Hansen, Chuck (1995a). Volume I: The Development of US Nuclear Weapons. Swords of Armageddon: US Nuclear Weapons Development since 1945. Sunnyvale, California: Chukelea Publications. ISBN 978-0-9791915-1-0. OCLC 231585284.

- Hansen, Chuck (1995b). Volume V: US Nuclear Weapons Histories. Swords of Armageddon: US Nuclear Weapons Development since 1945. Sunnyvale, California: Chukelea Publications. ISBN 978-0-9791915-0-3. OCLC 231585284.

- Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44132-3. OCLC 26764320.

- Home, R. W.; Low, Morris F. (September 1993). "Postwar Scientic Intelligence Missions to Japan". Isis. University of Chicago Press on behalf of History of Science Society. 84 (3): 527–537. doi:10.1086/356550. JSTOR 235645. S2CID 144114888.

- Ruhoff, John; Fain, Pat (June 1962). "The First Fifty Critical days". Mallinckrodt Uranium Division News. St. Louis: Mallinckrodt Incorporated. 7 (3). Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Serber, Robert; Rhodes, Richard (1992). The Los Alamos Primer: The First Lectures on How to Build an Atomic Bomb. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07576-5. OCLC 23693470. (Available on Wikimedia Commons)

- Smyth, Henry DeWolf (1945). Atomic Energy for Military Purposes: the Official Report on the Development of the Atomic Bomb under the Auspices of the United States Government, 1940–1945. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. OCLC 770285.

- Thayer, Harry (1996). Management of the Hanford Engineer Works In World War II: How the Corps, DuPont and the Metallurgical Laboratory Fast Tracked the Original Plutonium Works. New York: American Society of Civil Engineers Press. ISBN 0-7844-0160-8. OCLC 34323402.

- Waltham, Chris (20 June 2002). An Early History of Heavy Water (PDF). Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of British Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Weinberg, Alvin M. (21 July 1961). "Impact of Large-Scale Science on the United States". Science, New Series. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 134 (3473): 161–164. Bibcode:1961Sci...134..161W. doi:10.1126/science.134.3473.161. JSTOR 1708292. PMID 17818712.

- Participant accounts

- Bethe, Hans A. (1991). The Road from Los Alamos. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-74012-1. OCLC 22661282.

- Goudsmit, Samuel A. (1947). Alsos. New York: Henry Schuman. ISBN 0-938228-09-9. OCLC 8805725.

- Groves, Leslie (1962). Now it Can be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-306-70738-1. OCLC 537684.

- Libby, Leona Marshall (1979). Uranium People. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-16242-3. OCLC 4665032.

- Nichols, Kenneth David (1987). The Road to Trinity: A Personal Account of How America's Nuclear Policies Were Made. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-06910-X. OCLC 15223648.

- Ulam, Stanisław (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-520-07154-9. OCLC 1528346.