Northern line

The Northern line is a deep-level tube line on the London Underground, colored black on the Tube map. It carries more passengers than any other Underground line; 206,734,000 a year.

Northern line | |

|---|---|

1995 Stock leaving the tunnel north of Hendon Central | |

| Overview | |

| Type | Rapid transit |

| System | London Underground |

| Stations | 50 |

| Ridership | 252.310 million passenger journeys (2011/12)[1] |

| Website | tfl.gov.uk |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 18 December 1890 (as City and South London Railway) 28 August 1937 (renamed to Northern line) |

| Character | Deep-tube |

| Depot(s) | Golders Green, Morden; sidings at Edgware, Colindale, Hampstead, Chalk Farm, High Barnet, East Finchley, Archway, Camden Town, Euston (Bank branch), Moorgate, Charing Cross, Kennington, Tooting Broadway[2] |

| Rolling stock | 1995 Stock |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 58 km (36 mi) |

| Track gauge | Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Track gauge/data' not found. |

| Operating speed | 45 mph (72 km/h)[3] |

For most of its length it is a deep-level tube line.[nb 1] The portion between Stockwell and Borough opened in 1890 and is the oldest section of deep-level tube line on the Underground network. There were about 252 million passenger journeys recorded in 2011/12 on the Northern line, making it the second-busiest on the Underground. (It was the busiest from 2003 to 2010.) It is unique in having two different routes through central London. Despite its name, it does not serve the northern-most stations on the network, though it does serve the southern-most station, Morden, as well as 16 of the system's 29 stations south of the River Thames. There are 52 stations in total on the line, of which 38 have platforms below ground.

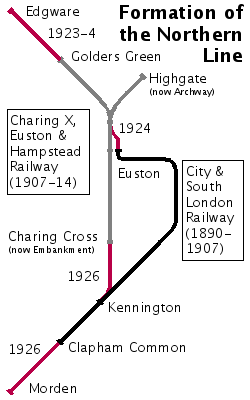

The line has a complicated history, and the current complex arrangement of two main northern branches, two central branches and the southern route reflects its genesis as three separate railways, combined in the 1920s and 1930s. An extension in the 1920s used a route originally planned by a fourth company. Abandoned plans from the 1920s to extend the line further southwards, and then northwards in the 1930s, would have incorporated parts of the routes of two further companies. From the 1930s to the 1970s, the tracks of a seventh company were also managed as a branch of the Northern line.[nb 2] An extension from Kennington to Battersea is currently under construction, which may either give the Northern line a second southern branch or may see it split into separate distinct lines with their own identities. It is coloured black on the current Tube map.

History

Early History

The City and South London Railway (C&SLR) was the first deep-level underground "tube" railway in the world,[4][note 1] and the first major railway to use electric traction. The railway was originally intended for cable-hauled trains, but owing to the bankruptcy of the cable contractor during construction, a system of electric traction using electric locomotives—an experimental technology at the time—was chosen instead. Given the small dimension of the tunnels as well as the difficulty of providing sufficient ventilation, steam power, as used on London's other underground railways, was not feasible for a deep tube railway. Like Greathead's earlier Tower Subway, the CL&SS was intended to be operated by cable haulage with a static engine pulling the cable through the tunnels at a steady speed.[5] Section 5 of the 1884 Act specified that:

The traffic of the subway shall be worked by ... the system of the Patent Cable Tramway Corporation Limited or by such means other than steam locomotives as the Board of Trade may from time to time approve.

The Patent Cable Tramway Corporation owned the rights to the Hallidie cable-car system first invented and used in San Francisco in 1873; trains were attached to the cable with clamps, which would be opened and closed at stations, allowing the carriages to disconnect and reconnect without needing to stop the cable or to interfere with other trains sharing the cable.[6] There were to be two independent endless cables, one between City station and Elephant and Castle moving at 10 mph, and the other between Elephant and Castle and Stockwell, where the gradient was less, at 12 mph. However, the additional length of tunnel permitted by the supplementary acts challenged the practicality of the cable system.

It is reported that this problem with the CL&SS contributed to the bankruptcy of the cable company in 1888.[7] However, electric motor traction had been considered all along, and much engineering progress had been made since the tunnel's construction had begun in 1886. So, CL&SS chairman Charles Grey Mott decided to switch to electric traction.[8] Other cable-operated systems using the Hallidie patents continued to be designed, such as the Glasgow Subway which opened in 1896.

The solution adopted was electrical power, provided via a third rail beneath the train, but offset to the west of center for clearance reasons. Although the use of electricity to power trains had been experimented with during the previous decade, and small-scale operations had been implemented, the C&SLR was the first major railway in the world to adopt it as a means of motive power.[6][note 2] The system operated using electric locomotives built by Mather & Platt collecting a voltage of 500 volts (actually +500 volts in the northbound tunnel and −500 volts in the southbound) from the third rail and pulling several carriages.[9] A depot and generating station were constructed at Stockwell.[note 3] Owing to the limited capacity of the generators, the stations were originally illuminated by gas.[10] The depot was on the surface, and trains requiring maintenance were initially hauled up via a ramp although, following a runaway accident, a lift was soon installed.[11] In practice, most rolling stock and locomotives went to the surface only for major maintenance.

To avoid the need to purchase agreements for running under surface buildings, the tunnels were bored below roadways, where construction could be carried out without charge.[7] At the northern end of the railway, the need to pass deep beneath the bed of the River Thames and the medieval street pattern of the City of London constrained the arrangement of the tunnels on the approach to King William Street station. Because of the proximity of the station to the river, steeply inclined tunnels were required to the west of the station. Because of the narrow street under which they ran, they were bored one above the other rather than side by side as elsewhere.[7] The outbound tunnel was the lower and steeper of the two. The tunnels converged immediately before the station, which was in one large tunnel and comprised a single track with a platform on each side.[note 4] The other terminus at Stockwell was also constructed in a single tunnel but with tracks on each side of a central platform.[note 5]

When opened in 1890, the line had six stations and ran for 3.2 miles (5.1 km)[14] in a pair of tunnels between the City of London and Stockwell, passing under the River Thames:

The original service was operated by trains composed of an engine and three carriages. Thirty-two passengers could be accommodated in each carriage,[10] which had longitudinal bench seating and sliding doors at the ends, leading onto a platform for boarding and alighting. It was reasoned that there was nothing to look at in the tunnels, so the only windows were in a narrow band high up in the carriage sides. Gate-men rode on the carriage platforms to operate the lattice gates and announce the station names to the passengers. Because of their claustrophobic interiors, the carriages soon became known as padded cells. These trains were however, preserved in London Transport Museum as the first static exhibit to the metro train.

The diameter of the tunnels restricted the size of the trains, and the small carriages with their high-backed seating were nicknamed padded cells. The railway was extended several times north and south, eventually serving 22 stations over a distance of 13.5 miles (21.7 km) from Camden Town in north London to Morden in Surrey.[14]

Although the C&SLR was well used, low ticket prices and the construction cost of the extensions placed a strain on the company's finances. In 1913, the C&SLR became part of the Underground Group of railways and, in the 1920s, it underwent major reconstruction works before its merger with another of the Group's railways, the Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway, forming a single London Underground line called the Morden-Edgware line. In 1933, the C&SLR and the rest of the Underground Group was taken into public ownership. Today, its tunnels and stations form the Bank Branch of the Northern line from Camden Town to Kennington and the southern leg of the line from Kennington to Morden.

The CCE&HR (commonly known as the "Hampstead Tube") was opened in 1907 and ran from Charing Cross (known for many years as Strand) via Euston and Camden Town (where there was a junction) to Golders Green and Highgate (now known as Archway). It was extended south by one stop to Embankment in 1914 to form an interchange with the Bakerloo and District lines. In 1913 the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), owner of the CCE&HR, took over the C&SLR, although they remained separate companies.

During the early 1920s, a series of works was carried out to connect the C&SLR and CCE&HR tunnels to enable an integrated service to be operated. The first of these new tunnels, between the C&SLR's Euston station and the CCE&HR's station at Camden Town, had originally been planned in 1912[16] but had been delayed by World War I. The second connection linked the CCE&HR's Embankment and C&SLR's Kennington stations and provided a new intermediate station at Waterloo to connect to the main line station there and the Bakerloo line. The smaller-diameter tunnels of the C&SLR were expanded to match the standard diameter of the CCE&HR and the other deep tube lines.

Extensions

In conjunction with the works to integrate the two lines, two major extensions were undertaken: northwards to Edgware in Middlesex (now in the London Borough of Barnet) and southwards to Morden in Surrey (then in the Merton and Morden Urban District, but now in the London Borough of Merton).

The Edgware extension used plans dating back to 1901 for the Edgware and Hampstead Railway (E&HR)[17] which the UERL had taken over in 1912. It extended the CCE&HR line from its terminus at Golders Green to Edgware in two stages: to Hendon Central in 1923 and to Edgware in 1924. The line crossed open countryside and ran on the surface, apart from a short tunnel north of Hendon Central. Five new stations were built to pavilion-style designs by Stanley Heaps, head of the Underground's Architects Office, stimulating the rapid northward expansion of suburban developments in the following years.

The engineering of the Morden extension of the C&SLR from Clapham Common to Morden was more demanding, running in tunnels to a point just north of Morden station, which was constructed in a cutting. The line then runs under the wide station forecourt and public road outside the station, to the depot. The extension was initially planned to continue to Sutton[18] over part of the route for the unbuilt Wimbledon and Sutton Railway, in which the UERL held a stake, but agreements were made with the Southern Railway to end the extension at Morden. The Southern Railway later built the surface line from Wimbledon to Sutton, via South Merton and St. Helier.[nb 3] The tube extension opened in 1926, with seven new stations, all designed by Charles Holden in a modern style. Originally, Stanley Heaps was to design the stations, but after seeing these designs Frank Pick, Assistant Joint Manager of the UERL, decided Holden should take over the project.[19] With the exception of Morden and Clapham South, where more land was available, the new stations were built on confined corner sites at main road junctions in areas that had been already developed. Holden made good use of this limited space and designed impressive buildings. The street-level structures are of white Portland stone with tall double-height ticket halls, with the famous London Underground roundel made up in coloured glass panels in large glazed screens. The stone columns framing the glass screens are surmounted by a capital formed as a three-dimensional version of the roundel. The large expanses of glass above the entrances ensure that the ticket halls are bright and, lit from within at night, welcoming.[20] The first and last new stations on the extension, Clapham South and Morden, include a parade of shops and were designed with structures capable of being built above (like many of the earlier central London stations). Clapham South was extended upwards soon after its construction with a block of apartments; Morden was extended upwards in the 1960s with a block of offices. All the stations on the extension, except Morden itself, are Grade II listed buildings.

The resulting line became known as the Morden–Edgware line, although a number of alternative names were also mooted in the fashion of the contraction of Baker Street & Waterloo Railway to "Bakerloo", such as "Edgmor", "Mordenware", "Medgway" and "Edgmorden".[21] With Egyptology very much in fashion after the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922, there was also a proposal to call the line the Tootancamden Line as it passed through both Tooting and Camden.[22] It was eventually named the Northern line from 28 August 1937,[23] reflecting the planned addition of the Northern Heights lines.[24]

After the UERL and the Metropolitan Railway (MR) were brought under public control in the form of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) in 1933, the MR's subsidiary, the Great Northern & City Railway, which ran from Moorgate to Finsbury Park, became part of the Underground as the Northern City Line. In preparation for the Northern Heights Plan, it was operated as part of the Northern line, although it was never connected to it.

The Northern Heights

In June 1935, the LPTB announced the New Works Programme, an ambitious plan to expand the Underground network which included the integration of a complex of existing London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) lines north of Highgate through the Northern Heights. These lines, built in the 1860s and 1870s by the Edgware, Highgate and London Railway (EH&LR) and its successors, ran from Finsbury Park to Edgware via Highgate, with branches to Alexandra Palace and High Barnet. The line taken over would be extended beyond Edgware to Brockley Hill, Elstree South and Bushey Heath with a new depot at Aldenham. The extension's route was that planned for the unbuilt Watford and Edgware Railway (W&ER), using rights obtained from the earlier purchase of the W&ER (which had long intended an extension of the EH&LR Edgware route towards Watford). This also provided the potential for further extension in the future; Bushey's town planners reserved space in Bushey village for a future station and Bushey Heath station's design was revised several times to ensure this option would remain available in the future.

The project involved electrification of the surface lines (operated by steam trains at the time), the doubling of the original single-line section between Finchley Central and the proposed junction with the Edgware branch of the Northern line, and the construction of three new linking sections of track: a connection between Northern City Line and Finsbury Park station on the surface; an extension from Archway to the LNER line near East Finchley via new deep-level platforms below Highgate station; and a short diversion from just before the LNER's Edgware station to the Underground's station of the same name.

The peak-hour service pattern was to be 21 trains an hour each way on the High Barnet branch north of Camden Town, 14 of them via the Charing Cross branch and seven via the Bank branch. 14 would have continued on beyond Finchley Central, seven each on the High Barnet and Edgware branches. An additional seven trains an hour would have served the High Barnet branch, but continued via Highgate High-Level and Finsbury Park to Moorgate, a slightly shorter route to the City. It does not seem to have been intended to run through trains to the ex-Northern City branch from Edgware via Finchley Central. Seven trains an hour would have served the Alexandra Palace branch, to/from Moorgate via Highgate High-Level. In addition to the 14 through trains described, the ex-Northern City branch would have had 14 four-car shuttle trains an hour.

Work began in the late 1930s, and was in progress on all fronts by the outbreak of World War II. The tunnelling northwards from the original Highgate station (now Archway) had been completed, and the service to the rebuilt surface station at East Finchley started on 3 July 1939, but without the opening of the intermediate (new) Highgate Station, at the site of the LNER's station of the same name. Further progress was disrupted by the start of the war, though enough had been made to complete the electrification of the High Barnet branch onwards from East Finchley over which tube services started on 14 April 1940; the new (deep-level) Highgate station opened on 19 January 1941. The single track LNER line to Edgware was electrified as far as Mill Hill East, including the Dollis Brook Viaduct, opening as a tube service on 18 May 1941 to serve the barracks there, thus forming the Northern line as it is today. The new depot at Aldenham had already been built and was used to build Halifax bombers. Work on the other elements of the plan was suspended late in 1939.

Preparatory work including viaducts and a tunnel had been started but not completed on the Bushey extension pre-war. After the war, the area beyond Edgware was made part of the Metropolitan Green Belt, largely preventing the anticipated residential development in the area, and the potential demand for services from Bushey Heath thus vanished. Available funds were directed towards completing the eastern extension of the Central line instead, and the Northern Heights plan was dropped on 9 February 1954. Aldenham depot was converted into an overhaul facility for buses.

The implemented service from High Barnet branch gave good access both to the West End and the City. This appears to have undermined traffic on the Alexandra Palace branch, still run with steam haulage to Kings Cross via Finsbury Park, as Highgate (low-level) was but a short bus ride away and car traffic was much lighter than it would become later. Consequently, the line from Finsbury Park to Muswell Hill and Alexandra Palace via the surface platforms at Highgate was closed altogether to passenger traffic in 1954. This contrasts with the decision to electrify the Epping-Ongar branch of the Central line, another remnant of the New Works program, run as a tube-train shuttle from 1957. A local pressure group, the Muswell Hill Metro Group, campaigns to reopen this route as a light-rail service. So far there is no sign of movement on this issue: the route, now the Parkland Walk, is highly valued by walkers and cyclists, and suggestions in the 1990s that it could, in part, become a road were met with fierce opposition. Another pressure group has proposed using the track bed further north, as part of the North and West London Light Railway. The connection between Drayton Park and the surface platforms at Finsbury Park was opened in 1976, when the Northern City Line became part of British Rail.

Recent developments

In 1975, the Northern City Line, known by that time as the Highbury branch, was transferred from London Underground to British Rail; it is now served by Great Northern. In the past, before the introduction of the 1995 stock, the Northern line was sometimes nicknamed the "Misery Line" in the press because of its perceived unreliability.[25][26]

In 2003, a train derailed at Camden Town. Although no one was hurt, points, signals and carriages were damaged, and the junctions there were not used while repairs were under way: trains coming from Edgware worked the Bank branch only, and trains from High Barnet and Mill Hill East worked the Charing Cross branch only. This situation was resolved when the junctions reopened, after much repair work and safety analysis and testing by contractor, on 7 March 2004.

On 7 July 2005 a defective train on the Northern line (causing its subsequent suspension) saved a Northern line train from being blown up as part of a terrorist attack on the London Underground and bus systems. Three trains on the Circle and Piccadilly lines were blown up. The Northern line bomber-to-be instead boarded a bus, which he later blew up.

On 13 October 2005 the Northern line service was suspended due to maintenance problems with the emergency braking system on the entire train fleet.[27] A series of rail replacement buses was used to connect outlying stations with other Underground lines.[28] Full service was restored on 18 October.

From June 2006, the service between East Finchley and Camden Town was suspended for two non-consecutive weekends every month, with service on the Edgware branch suspended for the other two weeks. This was part of Tube Lines's redevelopment of some Edgware and High Barnet Branch stations, including replacement of track, signals, as well as station maintenance.[29] This included refurbishment of all High Barnet branch stations from West Finchley to Camden Town. In October 2006, off-peak service between Mill Hill East and Finchley Central was cut back to a shuttle, except for a few weekend through trains.

On 13 August 2010, a defective rail maintenance train caused disruption on the Charing Cross branch, after it travelled four miles in 13 minutes without a driver. The train was being towed to the depot after becoming faulty. At Archway station, the defective train became detached and ran driverless until coming to a stop at an incline near Warren Street station. This caused morning rush-hour services to be suspended on this branch. All passenger trains were diverted via the Bank branch, with several not stopping at stations until they were safely on the Bank branch.[30][31]

The Northern line was originally scheduled to switch to automatic train operation in 2012, using the same SelTrac S40 system[32] as used since 2009 on the Jubilee line and for a number of years on the Docklands Light Railway.[33] Originally the work was to follow on from the Jubilee line so as to benefit from the experience of installing it there, but that project was not completed until spring 2011. Work on the Northern line was contracted to be completed before the 2012 Olympics. It is now being undertaken in-house, and TfL predicted the upgrade would be complete by the end of 2014.[34] The first section of the line (West Finchley to High Barnet) was transferred to the new signalling system on 26 February 2013[35] and the line became fully automated on 1 June 2014 with the Chalk Farm to Edgware via Golders Green section being the last part of the line to switch to ATO.[source?]

Northern Line Media

References

- ↑ "LU Performance Data Almanac". Transport for London. 2011–2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ "Northern line facts". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ↑ "Which London Underground line is the fastest? | CityMetric". www.citymetric.com. 18 September 2017. Retrieved 2019-02-09.[dead link]

- ↑ Wolmar 2005, p. 4.

- ↑ Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 36.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wolmar 2005, p. 135.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 35.

- ↑ Greathead 1896, p. 7.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2008, p. 44.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Wolmar 2005, p. 137.

- ↑ Wolmar 2005, p. 134.

- ↑ Connor 1999, p. 9.

- ↑ Connor 1999, p. 118.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Length of line calculated from distances given at "Clive's Underground Line Guides, Northern line, Layout". Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ↑ Rose 1999.

- ↑ No. 28665. 22 November 1912. p. 8798. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/28665/page/8798

- ↑ No. 27380. 26 November 1901. p. 8200. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/27380/page/8200

- ↑ No. 32770. 24 November 1922. p. 8314. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/32770/page/8314 more than one of

|page=and|pages=(help) - ↑ "Underground Journeys: Moving Underground". www.architecture.com. Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ↑ "Underground Journeys: South Wimbledon". www.architecture.com. Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ↑ Wolmar 2004, "Reaching Out", p. 225.

- ↑ Robert Graves and Alan Hodge, "The Long Weekend," p. 192 ISBN 0393311368

- ↑ Rails through the Clay; Croome & Jackson; London; 2nd ed; 1993; p228

- ↑ "London Tubes' New Names – Northern and Central Lines". The Times (47772): 12. 25 August 1937. Retrieved 18 May 2009.(subscription needed)

- ↑ "Call for action on Northern Line". BBC News. 12 October 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/london/4334700.stm. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- ↑ Stebbings, Peter (11 September 2006). "Five more years of Northern line pain". This Is Local London. http://www.thisislocallondon.co.uk/news/topstories/914725.0/. Retrieved 26 August 2008.

- ↑ "Travel Delays as Tube Line Shut". BBC News (London). 13 October 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/london/4335994.stm. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ↑ Transport for London (13 October 2005). "No Service on the Northern Line". Press release. http://www.tfl.gov.uk/corporate/media/newscentre/archive/3875.aspxe. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ↑ "Map of Upgrades" (PDF). Tube Lines. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ↑ "Runaway train on London Tube's Northern Line". BBC News. 13 August 2010. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-10964766. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ↑ Runaway of an engineering train from Highgate 13 August 2010 (Technical report). RAIB. 2011. 09-2011.

- ↑ Gareth Corfield (9 August 2016). London's 'automatic' Tube trains suffered 750 computer failures last year. https://www.theregister.co.uk/2016/08/09/london_underground_trains_stopped_750_times_automatic_train_operation_failure/. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ↑ Tube Lines (24 August 2005). "Network Tests for New Signalling Systems". Press release. Archived from the original on 5 January 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080105201220/http://www.tubelines.com/news/releases/200602/20050824.aspx.

- ↑ "Operational and Financial Performance Report and Investment Programme Report – Third Quarter, 2012/13" (PDF). Transport for London. 6 February 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ↑ Transport for London (26 February 2013). "Northern line upgrade one step closer". Press release. http://www.tfl.gov.uk/corporate/media/newscentre/archive/27303.aspx.

- ↑ A "tube" railway is an underground railway constructed in a cylindrical tunnel by the use of a tunnelling shield, usually deep below ground level.

- ↑ The seven companies were 1. the City & South London Railway, 2. the Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway, 3. the Edgware, Highgate & London Railway, 4. the Edgware & Hampstead Railway, 5. the Watford & Edgware Railway, 6. The Wimbledon & Sutton Railway and 7. the Great Northern & City Railway.

- ↑ The stations that the C&SLR were to serve on the W&SR, would not have included all those subsequently built by the Southern Railway. South Morden (not built), Sutton Common, Cheam (not built) and Sutton, would have been served, but Morden South, St Helier and West Sutton were not part of the UERL's plan.

Notes

- ↑ A "tube" railway is an underground railway constructed in a cylindrical tunnel by the use of a tunnelling shield, usually deep below ground level.

- ↑ Electric traction had been used for a number of tramway systems during the 1880s, starting with the Berlin tram system, which opened its first electric line in 1881.

- ↑ Greathead's plan presented to the Institution of Civil Engineers, shows the depot and generating station were on the east side of Clapham Road/Kennington Park Road, approximately where Stockwell Gardens is today.

- ↑ The original arrangement was a legacy of the intention to use cable haulage, and would have simplified operations if that method had been used. Instead, it proved a cause of congestion for electric locomotives, and King William Street station was reconfigured in 1895 to have one central platform with a track on each side.[12]

- ↑ The station was rebuilt in the 1920s in the conventional way, with separate tunnels for each platform. The new platforms were south of the original, and were constructed by enlarging the running tunnels.[13]

Lua error in Module:Attached_KML at line 224: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).