Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun (Tutankhaten, Tutankhamen) was an Egyptian Pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (royal family) during the New Kingdom.[1] He reigned from when he was nine years old (1334 BC) to when he died (1324 BC).

Tutankhamun was the son of Akhenaten and one of Akhenaten's sisters,[2] or perhaps one of his cousins, Kiya.[3] Tutankhamun ruled for 9 years and died very young, at 19, so he is known as The Boy King. He was married to his half-sister Ankhesenamun, daughter of Queen Nefertiti, his stepmother.

In his third year of his reign, Tutankhamun reversed several changes made during his father's reign. He ended the worship of the god Aten and restored the god Amun to supremacy. The ban on the cult of Amun was lifted and traditional privileges were restored to its priesthood. The capital was moved back to Thebes and the city of Akhenaten abandoned.[4] This is when he changed his name to Tutankhamun, "Living image of Amun", reinforcing the restoration of Amun.

In 1922 Howard Carter found Tutankhamun's tomb. Tutankhamen was believed to carry a curse. Actually, the archeologists who visited his tomb died from natural causes. Tutankhamen's tomb's unique and priceless treasures have taught us a lot about the boy king, the pharaohs, and ancient Egypt.[5]

Illness and death

Recent studies of his body using CT scans and DNA tests show that he had two children, but they died very young. Scientists now believe he died from a broken leg, made more complicated by bone disease and malaria.[6] Before this discovery there were many theories about his early death, including murder. It is quite certain that he was infected by several strains of malaria, and very likely that he had some genetic defects caused by inbreeding. His parents were brother and sister.[7] The final cause of his death is still unclear.

New galleries in Cairo Museum

In 2014 the Egyptian Museum in Cairo opened four new halls in the Tutankhamun Gallery.[8]

Tutankhamun Media

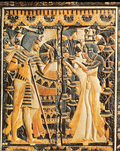

Tutankhamun and his queen, Ankhesenamun

Quartzite statue thought to be of Tutankhamun from temple complex at Medinet Habu

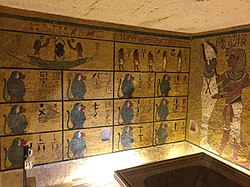

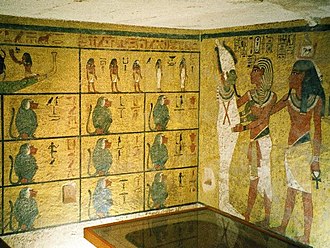

The wall decorations in KV62's burial chamber are modest in comparison with other royal tombs found in the Valley of the Kings

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- ↑ Clayton, Peter A. 2006. Chronicle of the Pharaohs: the reign-by-reign record of the rulers and dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28628-9

- ↑ Hawass, Zahi; et al. (2010). "Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family". Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (7): 640–641. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ↑ Powell, Alvin (12 February 2013). A different take on Tut. http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2013/02/a-different-take-on-tut/?utm_source=SilverpopMailing&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=02.12.13.xxx%2520%281%29.

- ↑ Erik Hornung, Akhenaten and the religion of light, Translated by David Lorton, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8014-8725-0.

- ↑ "3.3 History Through Objects: Tut's Treasures". Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ Hasan, Lama (2010). "How King Tut died revealed in new study". ABC World News. ABC. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ↑ Hawass Z. et al 2010. Ancestry and pathology in King Tutankhamun's family. Supreme Council of Antiquities, Cairo, Egypt. JAMA. 303(7):638-47. [1]

- ↑ BBC News: Egypt unveils renovated Tutankhamun gallery

- ↑ Robinson 2009.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Collier & Manley 2003.