Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was a forced movement of Native Americans in the United States between 1836 and 1839. The United States government forced Native Americans to leave their lands and move outside the United States. The U.S. then took over the Native Americans' lands and made the United States bigger. Many Cherokee died from the harsh weather, disease, or lack of food and water.

| |

| Date | Began May 26, 1838 |

|---|---|

| Location | Georgia to Oklahoma |

| Cause | Indian Removal Act, U.S. expansion, racism |

| Participants | 15,000 Cherokee; 7,000 U.S. soldiers[1] |

| Outcome | Forced removal of the Cherokee from their land |

| Casualties | |

| 353 Cherokee in concentration camps[2] | |

| 4,000 Cherokee on the Trail[3][4] | |

Because thousands of Native Americans died this forced move, it is called the "Trail of Tears."

Reasons

In 1827, gold was found near Dahlonega in Georgia. This resulted in a gold rush.[5] But at that time, a Native American nation called the Cherokees lived in Georgia. Many Cherokee children went to American schools. The Cherokees had their own newspaper and built three-story houses. Some even owned slaves.

Even so, President Andrew Jackson wanted this land to belong to the United States. The land was worth over $7,000,000 (about $179.5 million in 2015 U.S. dollars).[6] Jackson signed a law that forced the Cherokees to move. This was called the Indian Removal Act.[7] However, at that time, the Cherokees had their own nation and their own government. They did not have to follow laws made by the United States. Therefore, Jackson signed laws that let him take nearly all the Cherokees' rights.[8]

The Cherokee nation did not want to accept those laws or the Indian Removal Act, so the Cherokees' Chief John Ross decided to try to defend the Cherokee rights through the United States courts. In 1832, the Supreme Court of the United States said that the Cherokee were living in their own country, "in which the laws of Georgia can have no force."[9] The Court said Georgia had no right to make the Cherokee do anything.

Nevertheless, the U.S. government used a treaty, called the Treaty of New Echota, to remove the Cherokee nation by force. The treaty was signed by the leader of a small group of Cherokees who had different opinions than the rest of the Nation.[10] Since the treaty was not signed by an official Cherokee leader, it was not legal under Cherokee law. About 15,000 Cherokees signed a petition against the treaty. Newspapers and people around the United States (including John Quincy Adams) protested the treaty.[11]pp. 36, 41 The United States Senate approved the treaty by just one vote. President Jackson signed the treaty into law on May 23, 1836. The treaty gave the Cherokees two years to leave their lands.[11]p. 36

Forced removal

| “ | "I fought through the War Between the States and have seen many men shot, but the Cherokee Removal was the cruelest work I ever knew." - A Georgia soldier who participated in the removal [12] |

” |

The deadline for Cherokees to leave their land voluntarily was on May 23, 1838.[11]p. 36 President Martin Van Buren sent General Winfield Scott to lead the soldiers who would force the Cherokee to leave.[11]p. 41 Scott ordered his soldiers to "show every possible kindness to the Cherokee and to arrest any soldier who [gave] a [cruel] injury or insult [to] any Cherokee man, woman, or child."[3]

On May 26th, the operation began. 7,000 soldiers forced about 15,000 Cherokees and 2,000 of their slaves to leave their land.[1] All Cherokees had to leave their homes right away. Within three weeks, the Cherokees were all forced into internment camps. They were forced to stay in these camps for the summer of 1838.[11]pp. 41–42 353 Cherokee died from dysentery and other diseases.[2]

Finally Chief Ross got General Scott to agree to a deal. Chief Ross promised that he and other Cherokee leaders would bring the Cherokee people to their new lands on their own. General Scott agreed and even got the U.S. Army to pay the costs for the trip.[2]

The Cherokee travelled in groups of 1000 to 3000 people on three main routes. Different groups started in Chattanooga, Tennessee; Guntersville, Alabama; and Charleston, Tennessee. Most Cherokees had to walk; others, if they were wealthy men, could use wagons. The United States government also gave the Cherokee about 660 wagons.

The trip was about 1,200 miles long. During the trip, the Cherokees had to deal with winter weather, blizzards, and diseases. Not everybody agrees on how many people died on the trip. Some say 2,000 and others say 6,000, but most say about 4,000 people died.[3][4] This was one out of every four people in the Cherokee population.[13] They died from diseases like pneumonia, from freezing to death, from drinking bad water, and from other causes.[13] About half of them died in camps, and the other half during the trip.[14]

It is said that many Cherokees sang a Cherokee version of the song Amazing Grace, which became a kind of anthem for the Cherokee nation.[15][16]

Finally the Cherokee who were still alive arrived in what is now Oklahoma.

Routes

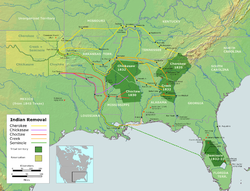

There were different routes the Cherokees took. Some were by land and others by water. Some boats were destroyed, which was a danger on water routes. On the ground, people had to walk through mud and cold weather and it was harder walking on land.

Water route

This route was taken by three groups, in total 2,800 Cherokees. The first group left on June 6 and reached the territory after 13 days. All groups started at Ross's Landing at the Tennessee River. They used boats to travel to the Ohio River. They then took this river southward, which took them to the Mississippi River. From there they moved through the Arkansas River westwards. They arrived near Fort Coffee, Oklahoma. The second and third group had a lot of problems with diseases, so their trip took longer.

Land routes

All others took land routes. They traveled in groups with a size of 700-1,600 people, all led by conductors chosen by John Ross, except for those, who signed the Treaty of New Enchota. They were led by United States soldiers. They usually took the southern route, and John Ross' groups the northern route. Both sides used already existing "roads". Most Cherokees took the northern route. The route lead through central Tennessee, southwestern Kentucky, and southern Illinois. The groups crossed the Mississippi north of Cape Girardeau, Missouri, then traveled through southern Missouri and west of Arkansas. Many died because of diseases, lack of water and bad road conditions. All land routes usually ended near Westville, Oklahoma. There were many more different land routes only taken by few people. These routes cover more than 2,200 miles in 9 states.

Trail Of Tears Media

A map of the process of Indian Removal, 1830–1838. Oklahoma is depicted in light yellow-green.

George W. Harkins, Choctaw chief.

Alexis de Tocqueville, French political thinker and historian

Seminole warrior Tuko-see-mathla, 1834

Selocta Chinnabby (Shelocta) was a Muscogee chief who appealed to Andrew Jackson to reduce the demands for Creek lands at the signing of the Treaty of Fort Jackson.

Historic Marker in Marion, Arkansas, for the Trail of Tears

Fragment of the Trail of Tears still intact at Village Creek State Park, Arkansas (2010)

Related pages

- Native Americans in the United States

- Manifest Destiny (the idea that the U.S. had the God-given right to take the lands they wanted)

- Forced migration

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Carter III, Samuel (1976). Cherokee Sunset: A Nation Betrayed. A Narrative of Travail and Triumph, Persecution and Exile. New York: Doubleday. p. 232. ISBN 978-0385067355.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jones, Billy (1984). Cherokees: An Illustrated History. Muskogee, Oklahoma: The Five Civilized Tribes Museum. pp. 74–81. ISBN 0-86546-059-0.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Rozema, Vicki (1995). Footsteps of the Cherokee. Winston-Salem, North Carolina: John F. Blair. p. 52. ISBN 0-89587-133-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Indian Treaties and the Removal Act of 1830". Office of the Historian. United States Department of State. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ↑ Inskeep, Steve. (2015) Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab. New York: Penguin Press. pp. 332-333. ISBN 978-1-59420-556-9.

- ↑ Gregg, Matthew T (2009). "Shortchanged: Uncovering the Value of Pre-Removal Cherokee Property". The Chronicles of Oklahoma. 3: 320–325.

- ↑ Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and his Indian Wars. New York: Viking, 2001. p.257. ISBN 0-670-91025-2.

- ↑ Perdue, Theda; Michael D. Green (2004). The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents. ISBN 0-312-08658-X.

- ↑ Burke, Joseph C. (1969). "The Cherokee Cases: A Study in Law, Politics, and Morality". Stanford Law Review. Stanford Law Review, Vol. 21, No. 3. 21 (3): 500–531. doi:10.2307/1227621. JSTOR 1227621.

- ↑ Starr, Emmet (1967). History of the Cherokee Indians. Fayetteville, North Carolina: Indian Heritage Association. p. 86. ASIN B0047UTKF0.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Logan, Charles Russell. The Promised Land: The Cherokees, Arkansas, and Removal, 1794-1839 (Report). Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Department of Arkansas Heritage.

- ↑ Remini, Robert (2000). "Invasion". The Earth Shall Weep: A History of Native America. Grove Press. p. 170. ISBN 0-8021-3680-X.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Trail of Tears National Historic Trail: Stories". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Cherokee Removal Memorial". Cherokee Removal Memorial Park. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ↑ Turner, Steve (2003). Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song. Harper Collins. p. 167. ISBN 978-0060002190.

- ↑ Duvall, Deborah L. (2000). An Oral History of Tahlequah: The Cherokee Nation. Arcadia Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-0738507828.

Other websites

- Videos about the Trail of Tears (free online) from the National Park Service

- Trail of Tears video Archived 2017-01-13 at the Wayback Machine from PBS

- Cherokee Removal - The Trail Where They Cried Archived 2006-02-02 at the Wayback Machine