Alcohol withdrawal

Alcohol withdrawal (also called alcohol withdrawal syndrome) is medical problem. It is a set of symptoms that can happen when a person who has drunk alcohol for a long time stops drinking. It can also happen when a person starts drinking less than they used to.

Alcohol withdrawal can be very dangerous. In the worst cases, it can even kill a person. This is why it is dangerous for people who drink a lot to stop drinking without talking to a doctor first.

Why does withdrawal happen?

Alcohol is a central nervous system depressant. This means that alcohol slows down the activity in some parts of the brain. This can create good feelings, like feeling relaxed and happy.

If a person drinks a lot of alcohol, eventually their body will get used to the alcohol. After a while, the person will need to drink more and more alcohol to feel drunk and to slow down parts of their brain. This is called tolerance.

Once the body is used to having alcohol (and having parts of the brain slowed down), suddenly taking away the alcohol will cause withdrawal symptoms. The central nervous system is used to being slowed down by alcohol. So without alcohol, the central nervous system gets very excited and over-active.

A person who gets tolerant to alcohol, and gets withdrawal symptoms when they stop drinking, is physically dependent on alcohol. This is also called physical addiction.

Who gets alcohol withdrawal?

Not everybody who drinks a lot of alcohol gets withdrawal symptoms when they stop. No one knows why some people get withdrawal symptoms and others do not.[1]

About half of people with alcoholism will get withdrawal symptoms if they drink less than usual.[1] About 5% to 20% of patients withdrawing from alcohol will get the most dangerous form of alcohol withdrawal: delirium tremens.[2] About 1/3 (one out of three) people who have withdrawal seizures will get delirium tremens.[2]

Symptoms of alcohol withdrawal

Symptoms of alcohol withdrawal are mostly caused by a central nervous system that is over-excited and working too hard.[3]

Everybody has a different set of withdrawal symptoms. Some people have only mild symptoms, like being unable to sleep or feeling anxious. Other people have very bad, life-threatening symptoms, like delirium, hallucinations, very high blood pressures, and very high fevers.

Withdrawal usually begins 6 to 24 hours after a person takes their last drink.[4] Acute withdrawal can last for up to one week.[5]

Diagnosis

To be diagnosed with alcohol withdrawal syndrome, patients must have at least two of these symptoms:.[6]

- Tremors in the hands

- Insomnia (trouble sleeping)

- Nausea or vomiting

- Hallucinations (seeing, hearing, or feeling things that are not really there)

- Anxiety

- Being agitated (unable to sit still)

- Tonic-clonic seizures (seizures where the person is not awake and jerks around)

- Autonomic instability (quickly changing symptoms related to the autonomic nervous system, like high blood pressure and high fevers

How bad are the symptoms?

Many things affect how bad alcohol withdrawal symptoms can be. The most important things are:[6]

- How much alcohol a person has drunk;

- How long the person has been drinking; and

- Whether the person has had alcohol withdrawal symptoms before

Symptoms are also grouped together and put into categories based on how bad they are:

- Alcohol hallucinosis: Patients may see, hear, or feel things that are not there, but have no other symptoms. These hallucinations will stop when alcohol withdrawal is over.[6]

- Withdrawal seizures: Seizures happen within 48 hours after the person stops drinking alcohol. A person may have a single generalized tonic-clonic seizure, or a brief episode of multiple seizures.[2]

- Delirium tremens: This is the worst form of alcohol withdrawal, and can kill a person. It usually happens 24 to 72 hours after the person stops drinking alcohol.[6] For more information, see the page on delirium tremens.

Order of symptoms

Every person goes through alcohol withdrawal differently. Even the worst of alcohol withdrawal symptoms can happen as soon as 2 hours after a person stops drinking. Because of this, it is best to talk to a doctor, go into the hospital, or get treatment before a person stops drinking alcohol. In many people, however, symptoms usually happen in this order:

Six to 12 hours after the last drink:[7]

Twelve to 24 hours after the last drink:

24 to 48 hours after the last drink:

- Some alcoholics will have seizures, and may even go into status epilepticus.[7] This can kill a person.

- The person will still have all of the other symptoms they had earlier.

48 hours after the last drink:

Usually, people will start to feel better after 48 hours. But sometimes, after 48 hours, alcohol withdrawal can still get worse and turn into delirium tremens.[7] Delirium tremens can last anywhere from 4 to 12 days.

Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome (PAWS)

Acute alcohol withdrawal usually lasts only a week.[5] But many alcoholics have what is called Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome (PAWS) (also called "protracted alcohol withdrawal syndrome). This means that some withdrawal symptoms continue beyond the acute withdrawal stage. Some withdrawal symptoms can last for at least a year after a person stops drinking.

Symptoms

Symptoms of post-acute withdrawal syndrome (PAWS) can include:[8]

- Cravings for alcohol (wanting alcohol very, very badly)

- Anhedonia (not being able to enjoy things that a person normally likes)

- Not seeing, hearing, tasting, hearing, or smelling things as well as usual

- Feeling disoriented (meaning a person does not know who they are, where they are, or what is going on)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Headaches

Insomnia is also a common symptom of PAWS. It often keeps happening after acute (immediate) alcohol withdrawal. Research has showed that people with insomnia are more likely to relapse (start using alcohol again). Studies have found that magnesium or trazodone can help treat insomnia in recovering alcoholics.[9][10][11]

For some people, the acute phase of alcohol withdrawal can last longer than usual. Protracted (longer than usual) delirium tremens has been reported in medical research, but is not common.[12]

Treatment

People with bad alcohol withdrawal symptoms often need to go into a hospital to make sure they are safe while they are withdrawing from alcohol.[4]

Many different medicines can help with the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal:

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are the most commonly used medication for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. They can help decrease alcohol withdrawal symptoms and prevent seizures.[13]

The most commonly used benzodiazepines are long-acting (medications whose effects last a long time), like chlordiazepoxide and diazepam (Valium). These seem to be the best medicines for treating delirium, and do not have to be given as often.[5]

Although benzodiazepines work very well at treating alcohol withdrawal, they should be carefully used. Benzodiazepines should only be used for short periods in alcoholics. This is because alcoholics are more likely to get addicted to benzodiazepines. There is a risk of replacing an alcohol addiction with benzodiazepine dependence or adding another addiction.[14][15] Also, both alcohol and benzodiazepines are depressants. If a person takes both at the same time, they are more likely to get depression or become suicidal.[16]

Vitamins

Alcoholics often do not have enough of certain vitamins in their bodies. One of these important vitamins is thiamine. If a person does not have enough thiamine in their body, they can get serious health problems and even brain damage.

When a person is going through alcohol withdrawal, the most important vitamins are thiamine and folic acid. If an alcoholic who stops drinking does not have enough of these vitamins, they can get Wernicke syndrome, a very serious brain problem. To keep this from happening, people who have stopped drinking alcohol are often given thiamine and folic acid intravenously (through a needle placed into a vein). They may also be given other vitamins. This can help prevent Wernicke syndrome.[17]

Anticonvulsants

Sometimes, anticonvulsant (anti-seizure) medicines are given to try to prevent seizures.

Some evidence says that topiramate (Topamax),[18] carbamazepine (Tegretol), and other anticonvulsants are helpful in treating alcohol withdrawal; however, research is limited.[18][19]

Other studies have shown that benzodiazepines work just as well as anticonvulsants.[20]

Other medicines

Clonidine may be used along with benzodiazepines to help some of the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.[6]

Antipsychotic medicines, such as haloperidol, are sometimes used along with benzodiazepines to control agitation or psychosis.[6] However, antipsychotics have to be used carefully. They can make alcohol withdrawal worse, since they make it more likely for a person to have a seizure.[21]

Prognosis

If alcohol withdrawal is not treated correctly, people can die or have permanent brain damage.[22]

Alcoholics often cannot stop drinking alcohol after their withdrawal symptoms are over. Often, they need support for months or years after withdrawal is over.

Alcohol Withdrawal Media

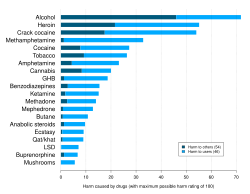

Table from the 2010 DrugScience study ranking various drugs (legal and illegal) based on statements by drug-harm experts. This study rated alcohol the most harmful drug overall, and the only drug more harmful to others than to the users themselves.

Related pages

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Schuckit, MA (27 November 2014). "Recognition and management of withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens)". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (22): 2109–13. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1407298. PMID 25427113. S2CID 205116954.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Manasco, A; Chang, S; Larriviere, J; Hamm, LL; Glass, M (November 2012). "Alcohol withdrawal". Southern Medical Journal. 105 (11): 607–12. doi:10.1097/smj.0b013e31826efb2d. PMID 23128805. S2CID 25769989.

- ↑ "Alcohol Withdrawal: Symptoms, Timeline & Detox Process". American Addiction Centers. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Muncie HL, Jr; Yasinian, Y; Oge', L (Nov 1, 2013). "Outpatient management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome". American Family Physician. 88 (9): 589–95. PMID 24364635.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 McKeon, A; Frye, MA; Delanty, N (August 2008). "The alcohol withdrawal syndrome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 79 (8): 854–62. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.128322. PMID 17986499. S2CID 2139796.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Bayard, Max; Mcintyre, Jonah; Hill, Keith; Woodside, Jack (March 2004). "Alcohol withdrawal syndrome". Am Fam Physician. 69 (6): 1443–50. PMID 15053409. Archived from the original on 2010-11-15. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Alcohol Withdrawal: Symptoms of Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome". WebMD. WebMD, LLC. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ↑ Martinotti G; Nicola MD; Reina D; Andreoli S; Focà F; Cunniff A; Tonioni F; Bria P; Janiri L (2008). "Alcohol protracted withdrawal syndrome: the role of anhedonia". Subst Use Misuse. 43 (3–4): 271–84. doi:10.1080/10826080701202429. PMID 18365930. S2CID 25872623.

- ↑ Hornyak M; Haas P; Veit J; Gann H; Riemann D (November 2004). "Magnesium treatment of primary alcohol-dependent patients during subacute withdrawal: an open pilot study with polysomnography". Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 28 (11): 1702–9. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000145695.52747.BE. PMID 15547457.

- ↑ Le Bon O; Murphy JR; Staner L; Hoffmann G; Kormoss N; Kentos M; Dupont P; Lion K; Pelc I; Verbanck P (August 2003). "Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of trazodone in alcohol post-withdrawal syndrome: polysomnographic and clinical evaluations". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 23 (4): 377–83. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000085411.08426.d3. PMID 12920414. S2CID 33686593.

- ↑ Borras L; de Timary P; Constant EL; Huguelet P; Eytan A (November 2006). "Successful treatment of alcohol withdrawal with trazodone". Pharmacopsychiatry. 39 (6): 232. doi:10.1055/s-2006-951385. PMID 17124647. S2CID 260250503.

{{cite journal}}: Check|s2cid=value (help) - ↑ Miller FT (March–April 1994). "Protracted alcohol withdrawal delirium". J Subst Abuse Treat. 11 (2): 127–30. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(94)90029-9. PMID 8040915.

- ↑ Bird, RD; Makela, EH (January 1994). "Alcohol withdrawal: what is the benzodiazepine of choice?". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 28 (1): 67–71. doi:10.1177/106002809402800114. PMID 8123967. S2CID 24312761.

- ↑ Sanna, Enrico; Mostallino, Maria Cristina; Busonero, Fabio; Talani, Giuseppe; Tranquilli, Stefania; Mameli, Manuel; Spiga, Saturnino; Follesa, Paolo; Biggio, Giovanni (December 17, 2003). "Changes in GABA(A) receptor gene expression associated with selective alterations in receptor function and pharmacology after ethanol withdrawal". Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (37): 11711–24. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11711.2003. ISSN 0270-6474. PMC 6740939. PMID 14684873. Archived from the original on 2010-11-15. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- ↑ Rassnick, Stefanie; Krechman, Jolie; Koob, George (April 1993). "Chronic ethanol produces a decreased sensitivity to the response-disruptive effects of GABA receptor complex antagonists". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 44 (4): 943–50. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(93)90029-S. PMID 8385785. S2CID 5909253.

- ↑ Ziegler PP (August 2007). "Alcohol use and anxiety". Am J Psychiatry. 164 (8): 1270, author reply 1270–1. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020291. PMID 17671296. Archived from the original on 2010-11-15. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- ↑ Hugh Myrick; Raymond F Anton (1998). "Treatment of Alcohol Withdrawal" (PDF). Alcohol Health & Research World. niaaa. 22 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-15. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hughes, JR. (June 2009). "Alcohol withdrawal seizures". Epilepsy Behav. 15 (2): 92–7. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.02.037. PMID 19249388. S2CID 20197292.

- ↑ Prince V; Turpin KR (June 1, 2008). "Treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome with carbamazepine, gabapentin, and nitrous oxide". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 65 (11): 1039–47. doi:10.2146/ajhp070284. PMID 18499876.

- ↑ Amato, Laura; Minozzi, Silvia; Vecchi, Simona; Davoli, Marina (2010). Amato, Laura (ed.). "Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3 (3): CD005063. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005063.pub3. PMID 20238336.

- ↑ Ebadi, Manuchair (23 October 2007). "Alphabetical presentation of drugs". Desk Reference for Clinical Pharmacology (2nd ed.). USA: CRC Press. p. 512. ISBN 978-1-4200-4743-1.

- ↑ Hanwella R, de Silva V (June 2009). "Treatment of alcohol dependence". Ceylon Med J. 54 (2): 63–5. doi:10.4038/cmj.v54i2.877. PMID 19670554.

- ↑ How to Stop Drinking Alcohol.org, 16 August, 2020