Big Bang

The Big Bang is a physical theory about how the universe started expanding, and then made the stars and galaxies we see today. The Big Bang is the name that scientists use for the most common theory of the universe,[2][3][4] from the very early stages to the present day.[5][6][7] The most commonly considered alternatives are called the Steady State theory and Plasma cosmology, according to both of which the universe has no beginning or end.[8]

| Date | 13.8 billion years ago |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | N/A |

| Type | Cosmic event |

| Theme | Formation of the universe |

| Cause | Unknown |

| Participants | All matter and energy in the universe |

| Outcome | Formation of the universe and the laws of physics |

According to the theory the Big Bang began as a very hot, small, and dense superforce (the mix of the four fundamental forces), with no stars, atoms, form, or structure (called a "singularity"). Then about 13.8 billion years ago,[1] space expanded very quickly (thus the name "Big Bang"). This started the formation of atoms, which eventually led to the formation of stars and galaxies. It was Georges who first noted (in 1927) that the universe is expanding. The universe is still expanding today, and getting colder as well.

As a whole, the universe is growing and the temperature is falling as time passes. Cosmology is the study of how the universe began and its development. Some scientists who study cosmology have agreed that the Big Bang theory matches what they have observed so far.[1]

Naming

Astronomer Fred Hoyle mockingly called the theory the "Big Bang" on his radio show. Scientists who did not agree with him decided to use it.[9]

Evidence

Scientists base the Big Bang theory on many different observations. The most important is the redshift of very far away galaxies. Cosmological redshift is the Doppler effect occurring in light. When an object moves away from Earth, its color rays look more similar to the color red than they actually are, because the movement stretches the wavelength of light given off by the object. Scientists use the word "red hot" to describe this stretched light wave because red is the longest wavelength on the visible spectrum. The more redshift there is, the faster the object is moving away. By measuring the redshift, scientists proved that the universe is expanding, and they can work out how fast the object is moving away from the Earth. With very exact observation and measurements, scientists believe that the universe was a singularity approximately 13.8 billion years ago. Because most things become colder as they expand, scientists assume that the universe was very small and very hot when it started.[10] This does not take into account other possible (non-cosmological) causes of redshift.

Other observations that support the Big Bang theory are the amounts of chemical elements in the universe. Amounts of very light elements, such as hydrogen, helium, and lithium seem to agree with the theory of the Big Bang. The same is true, however, for Static State theory and plasma cosmology. Scientists also detected what they call the cosmic microwave background radiation. These electromagnetic waves are everywhere in the universe. This radiation is now very weak and cold, but is thought to have been very strong and very hot a long time ago.[1]

Time

It can be said that time had no meaning before the Big Bang. If the Big Bang was the beginning of time, then there was no universe before the Big Bang, since there could not be any "before" if there was no time. Other ideas state that the Big Bang was not the beginning of time 13.8 billion years ago. Instead, some believe that there was a completely different universe before the Big Bang, and it may have been very different from the one we know today.[10]

Nonetheless, in November 2019, Jim Peebles, awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics for his theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology,[11] noted in his award presentation that he does not support the Big Bang Theory due to the lack of concrete supporting evidence, and stated, "It's very unfortunate that one thinks of the beginning whereas in fact, we have no good theory of such a thing as the beginning."[12]

Graphical timeline of the universe

Many things happened in the first picosecond of the universe's time:

Big Bang Media

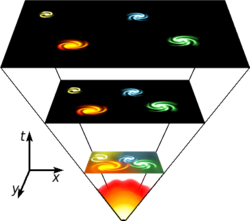

Timeline of the expansion of the universe, where space is represented schematically at each time by circular sections. On the left, the dramatic expansion of inflation; at the center, the expansion accelerates (artist's concept; neither time nor size are to scale).

Estimated relative distribution for components of the energy density of the universe. (In February 2015, the European-led research team behind the Planck cosmology probe released new data refining these values to 4.9% ordinary matter, 25.9% dark matter and 69.1% dark energy.)

Panoramic view of the entire near-infrared sky reveals the distribution of galaxies beyond the Milky Way. Galaxies are color-coded by redshift.

The cosmic microwave background spectrum measured by the FIRAS instrument on the COBE satellite is the most-precisely measured blackbody spectrum in nature. The data points and error bars on this graph are obscured by the theoretical curve.

9 year WMAP image of the cosmic microwave background radiation (2012). The radiation is isotropic to roughly one part in 100,000.

Focal plane of BICEP2 telescope under a microscope – used to search for polarization in the CMB

Chart shows the proportion of different components of the universe – about 95% is dark matter and dark energy.

Related pages

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 NASA. "Universe 101:Big Bang theory". Retrieved 2010-01-28.

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (20 February 2017). Cosmos Controversy: The Universe Is Expanding, but How Fast?. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/20/science/hubble-constant-universe-expanding-speed.html. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ Kurki-Suonio, Hannu (2018). Cosmology I. University of Helsinki. p. 9-10. http://www.helsinki.fi/~hkurkisu/cosmology/Cosm1.pdf. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ↑ Kornreich, Dave (27 June 2015). Can we find the place where the Big Bang happened? (Intermediate). Ask an Astronomer, Cornell University. http://curious.astro.cornell.edu/about-us/102-the-universe/cosmology-and-the-big-bang/the-big-bang/592-can-we-find-the-place-where-the-big-bang-happened-intermediate. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ↑ Silk, Joseph (2009). Horizons of Cosmology. Templeton Press. p. 208. ISBN 9781599473413.

- ↑ Singh, Simon (2005). Big Bang: The Origin of the Universe. Harper Perennial. p. 560. ISBN 9780007162215.

- ↑ Wollack, Eddie J. (10 December 2010). "Cosmology: The Study of the Universe". Universe 101: Big Bang Theory. NASA. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 2017-04-15.

The second section discusses the classic tests of the Big Bang theory that make it so compelling as the likely valid description of our universe.

- ↑ Lerner, Eric John (2004).

Open Letter on Cosmology / Cosmology Statement. New Scientist. Wikisource.

Open Letter on Cosmology / Cosmology Statement. New Scientist. Wikisource.

- ↑ Sullivan, Walter (August 22, 2001). "Fred Hoyle dies at 86; opposed 'Big Bang' but named it". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-28.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Chris LaRocco and Blair Rothstein. "The Big Bang: it sure was BIG!". Retrieved 2010-01-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Hooper, Dan (12 October 2019). "A Well-Deserved Physics Nobel – Jim Peebles' award honors modern cosmological theory at last". Scientific American. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/a-well-deserved-physics-nobel/. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ↑ Couronne, Ivan (14 November 2019). "Top cosmologist's lonely battle against 'Big Bang' theory". Phys.org. https://phys.org/news/2019-11-cosmologist-lonely-big-theory.html. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

More reading

- Caleb, Weedon (2005). Big Bang: the most important scientific discovery of all time and why you need to know about it. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-715252-0.