Augustus

Augustus (Latin: [Imperator Caesar Dīvī Fīlius Augustus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); 23 September 63 BC – 19 August 14 AD) was the first Roman Emperor, ruling from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He led Rome in its transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire.

| Augustus Caesar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Princeps | |||||

The statue known as the Augustus of Prima Porta, 1st century | |||||

| Roman Emperor | |||||

| 16 January 27 BC – 19 August 14 AD | |||||

| Successor | Tiberius | ||||

| Born | 23 September 63 BC (Roman calendar) Rome, Roman Republic | ||||

| Died | 19 August 14 (Julian calendar) (aged 76) Nola, Italy, Roman Empire | ||||

| Burial | Mausoleum of Augustus, Rome | ||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue | Julia the Elder | ||||

| |||||

| Imperial Dynasty | Julio-Claudian | ||||

| Father | Natural: Gaius Octavius; Adoptive: Julius Caesar (in 44 BC) | ||||

| Mother | Atia Balba Caesonia | ||||

| |

| These articles cover Ancient Rome and the fall of the Republic | |

| Roman Republic, First Triumvirate, Assassination of Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, Cleopatra VII, Pompey, Cicero, Second Triumvirate |

When Julius Caesar was assassinated, Augustus and his allies fought against the assassins and defeated them. Later, Augustus fought against his allies and defeated them.

Life

Octavian, as he was originally called, was the adopted son of the dictator of the Roman Republic, Julius Caesar. Octavian came into power in the Second Triumvirate. This was three men ruling over the Roman Republic: Mark Antony, Lepidus and Octavian.

All three were loyal to Julius Caesar, the assassinated dictator, killed in 44 BC. Following his death a civil war broke out across Rome, between those loyal to Caesar, and the conspirators, led by two of Caesar's assassins, Brutus and Cassius.

At first, Octavian was the junior partner in the triumvirate. Lepidus was more experienced in government, and Mark Antony was a fine military leader. The triumvirate defeated Brutus and Cassius at the Battle of Philippi, 42 BC, largely due to Antony's leadership. Then they split the leadership of the Republic three ways. Antony took the east, Lepidus took Spain and part of North Africa, and Octavian took Italy.

Antony followed in Caesar's footsteps by going to Egypt and becoming Cleopatra's lover. They had three children together. His absence from Rome allowed the intelligent Octavian to build up support.

The triumvirate broke up in 33 BC, and disagreement turned to civil war in 31 BC. Antony was defeated by Octavian at the naval Battle of Actium and then at Alexandria. He committed suicide, as did his lover, Cleopatra VII of Egypt, in 30 BC. Lepidus was sidelined, blamed for a revolt in Sicily, and removed from government. He died peacefully in exile in Circeii in Italy in the year 13 BC.

After winning the power struggle, Octavian was voted as Emperor by the Roman Senate in 31 BC. He took the name "Augustus" (which meant 'exalted'). He ruled until AD 14,[1] when his stepson and son-in-law Tiberius became Emperor in his place.

During his reign, some of those who were against his government were murdered (especially those senators who wanted to keep the Roman Republic). He promised to make Rome a Republic again, but instead proclaimed himself High Priest (Pontifex Maximus). Many temples in the provinces set up statues of him as one of their gods. The name of the month "August" in English (and most other European languages) comes from him.

His main accomplishment was the creation of the Roman Empire, a political structure that lasted for nearly five centuries more. He first recruited and set up the Praetorian Guard.

Ancient sources

Historians often use the Res Gestae Divi Augusti as a source for Augustus. It was written by him as an inscription on his tomb which recorded all his achievements.

The historian Tacitus is often used by historians. He gives an anti-Augustan perspective, whereas many other sources and histories were written to flatter Augustus (propaganda). Some examples of writers like these are Velleius Paterculus, Virgil, Ovid. The most famous work of Augustan propaganda is the Virgil's Aeneid

Cassius Dio presents a quite impartial account of Augustus as emperor: he was writing in the reign of a later emperor.

Portraits

Bust of Augustus, palace of Versailles, 17th century

Bust of Augustus in old-age, palace of Versailles

Augustus Media

Denarius from 44 BC, showing Julius Caesar on the obverse and the goddess Venus on the reverse of the coin. Caption: Template:Langr

The Death of Caesar by Vincenzo Camuccini. On 15 March 44 BC, Octavian's adoptive father Julius Caesar was assassinated by a conspiracy led by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome.

A bust of Augustus as a younger Octavian, dated c. 30 BC. Capitoline Museums, Rome

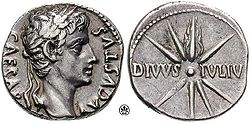

A denarius minted c. 18 BC. Obverse: Template:Langr; reverse: comet of eight rays with tail upward; Template:Langr, "divine Julius".

Fresco paintings inside the House of Augustus, his residence during his reign as emperor

Antony and Cleopatra, by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

The Battle of Actium, by Laureys a Castro, painted 1672, National Maritime Museum, London

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- ↑ Robinson Jr., C.A. (1964). "Introduction". Selections from Greek and Roman historians. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. xxix.