Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky (11 November 1821 – 9 February 1881) was a Russian novelist.[1][2][3] His most popular novels are Crime and Punishment, The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov. He is regarded as one of the greatest authors of all time.[4]

Fyodor Dostoyevsky | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Vasily Perov (1872) | |

| Born | Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoyevsky November 11, 1821 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | February 9, 1881 (aged 59) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire Emphysema |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, essayist |

| Language | Russian |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Period | 1846–1881 |

| Notable works | Notes from Underground Crime and Punishment The Idiot The Brothers Karamazov |

| Spouse | Mariya Dmitriyevna Isayeva (1857–64) [her death] Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina (1867–1881) [his death] |

| Children | Sofiya (1868), Lyubov (1869–1926), Fyodor (1871–1922), Alexei (1875–1878) |

| Signature | |

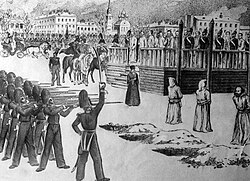

In his 20s he joined a group of radicals in St Petersburg. They were into French socialist ideas. A police agent reported the group to the authorities. On 22 April 1849, Dostoyevsky was arrested and imprisoned with the other members. After months of questioning and investigation they were tried. They were found guilty of planning to distribute subversive propaganda and condemned to death by firing squad.[5]

The punishment was changed to a sentence of exile and hard labour, but not before they were forced to go through a mock execution.[5] In 1859 a new tsar allowed Dostoyevsky to end his Siberian exile. A year later he was back in St Petersburg. The experience had cost him ten years of his life. It is the root of all his writing.[5]

- Dostoyevsky's experience had altered him profoundly... He was particularly scornful of the ideas he found in St Petersburg when he returned from his decade of Siberian exile. The new generation of Russian intellectuals was gripped by European theories and philosophies [which] were melded together into a peculiarly Russian combination that came to be called 'nihilism'.[5]

Religion

Raised in an educated and religious family, Dostoyevsky's beliefs changed through his life. In prison, he focused intensely on the figure of Christ and on the New Testament, the only book allowed in prison.[6] In a letter to the woman who had sent him the New Testament, Dostoyevsky wrote that he was a "child of unbelief and doubt up to this moment, and I am certain that I shall remain so to the grave". He also wrote that "even if someone were to prove to me that the truth lay outside Christ, I should choose to remain with Christ rather than with the truth".[6]

From an analysis of religious ideas in Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, The Demons (The Possessed), and The Brothers Karamazov, James Townsend thinks Dostoyevsky held orthodox Christian beliefs except for his view of salvation from sin. According to Townsend, "Dostoevsky almost seemed to embrace an in-this-life purgatory", in which people suffer to pay for their sins, rather than the Christian doctrine of salvation through Christ.[7] Malcolm Jones sees elements of Islam and Buddhism in Dostoyevsky's religious convictions.[6] Colin Wilson in The Outsider describes him as a "tormented half-atheist-half-Christian".[8]

His work

Many scholars see Dostoyevsky as one of the greatest psychologists in literature.[9] His works have had a big effect on twentieth-century fiction. Very often, he wrote about characters who live in poor conditions. Those characters are sometimes in extreme states of mind. They might show both a strange grasp of human psychology as well as good analyses of the political, social and spiritual states of Russia of Dostoevsky's time. Many of his best-known works are prophetic.[10] He is sometimes considered to be a founder of existentialism, most frequently for Notes from Underground, which has been described as "the best overture for existentialism ever written".[11] He is also famous for writing The Brothers Karamazov, which many critics, such as Sigmund Freud, have said was one of the best novels ever written.

Demons

His attack on nihilism is in his great novel Demons, or The Possessed. Published in 1872, it is a "dark comedy, cruelly funny in its depiction of high-minded intellectuals toying with revolutionary notions without understanding anything of what revolution means in practice".[5]

The plot is a version of actual events at the time. A former teacher of divinity turned terrorist, Sergei Nechaev, had written a pamphlet, The Catechism of a Revolutionary, which argued that any means (including blackmail and murder) could be used to advance the cause of revolution. Nechaev planned to kill a student who questioned his ideas.[5][12]

One of the characters in Demons confesses: "I got entangled in my own data, and my conclusion contradicts the original idea from which I start. From unlimited freedom, I conclude with unlimited despotism". This suggests that the result of abandoning morality for the sake of an idea will be tyranny more extreme than any in the past.[5]

List of works

English versions of titles come after the Russian title.

Novels

- 1846 - Bednye lyudi (Бедные люди); Poor Folk

- 1846 - Dvojnik (Двойник. Петербургская поэма); The Double: A Petersburg Poem

- 1849 - Netochka Nezvanova (Неточка Незванова); Netochka Nezvanova (this is a feminine name)(Unfinished)

- 1859 - Dyadushkin son (Дядюшкин сон); The Uncle's Dream

- 1859 - Selo Steanchikovo i ego obitateli (Село Степанчиково и его обитатели); The Village of Stepanchikovo

- 1861 - Unizhennye i oskorblennye (Униженные и оскорбленные); The Insulted and Humiliated

- 1862 - Zapiski iz mertvogo doma (Записки из мертвого дома); The House of the Dead

- 1864 - Zapiski iz podpolya (Записки из подполья); Notes from Underground

- 1866 - Prestuplenie i nakazanie (Преступление и наказание); Crime and Punishment

- 1867 - Igrok (Игрок); The Gambler

- 1869 - Idiot (Идиот); The Idiot

- 1870 - Vechnyj muzh (Вечный муж); The Eternal Husband

- 1872 - Besy (Бесы); various English titles: The Possessed; The Devils; Demons

- 1875 - Podrostok (Подросток); The Raw Youth

- 1881 - Brat'ya Karamazovy (Братья Карамазовы); The Brothers Karamazov

Novellas and short stories

- 1846 - Gospodin Prokharchin (Господин Прохарчин); Mr. Prokharchin

- 1847 - Roman v devyati pis'mah (Роман в девяти письмах); Novel in Nine Letters

- 1847 - Hozyajka (Хозяйка); The Landlady

- 1848 - Polzunkov (Ползунков); Polzunkov

- 1848 - Slaboe serdze (Слабое сердце); A Weak Heart

- 1848 - Chestnyj vor (Честный вор); An Honest Thief

- 1848 - Elka i svad'ba (Елка и свадьба); A Christmas Tree and a Wedding

- 1848 - Chuzhaya zhena i muzh pod krovat'yu (Чужая жена и муж под кроватью); The Jealous Husband

- 1848 - Belye nochi (Белые ночи); White nights

- 1849 - Malen'kij geroj (Маленький герой); A Little Hero

- 1862 - Skvernyj anekdot (Скверный анекдот); A Nasty Story

- 1865 - Krokodil (Крокодил); The Crocodile

- 1873 - Bobok (Бобок); Bobok

- 1876 - Krotkaja (Кроткая); A Gentle Creature

- 1876 - Muzhik Marej (Мужик Марей); The Peasant Marey

- 1876 - Mal'chik u Hrista na elke (Мальчик у Христа на ёлке); The Heavenly Christmas Tree

- 1877 - Son smeshnogo cheloveka (Сон смешного человека); The Dream of a Ridiculous Man

The last five stories (1873-1877) are included in A Writer's Diary.

Non-fiction

- Winter Notes on Summer Impressions (1863)

- A Writer's Diary (Дневник писателя) (1873–1881)

- Letters

Fyodor Dostoyevsky Media

A sketch of the Petrashevsky Circle mock execution

Dostoevsky as a military engineer in 1858 or -59, portrait by Solomon Leibin (Соломон Лейбин)

Dostoevsky on his bier, drawing by Ivan Kramskoi, 1881

Related pages

References

- ↑ Old style date: 30 October 1821 – 28 January 28.

- ↑ Russian: Фёдор Миха́йлович Достое́вский, Fëdor Mihajlovič Dostoevskij, sometimes transliterated Dostoevsky

listen (info • help)

listen (info • help)

- ↑ "185 лет со дня рождения Федора Достоевского". Voice Ukraine (in Russian). 1 December 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Lauer, Reinhard (2003). Geschichte der russischen Literatur: von 1700 bis zur Gegenwart (in Deutsch). Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-50267-5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Gray, John 2014. A point of view: The writer who foresaw the rise of the totalitarian state. BBC News Magazine. [1]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Jones, Malcolm V. 2005. Dostoevsky and the dynamics of religious experience. Anthem Press, p6/9; p68/9. ISBN 978-1-84331-205-5

- ↑ Townsend, James (1997). "Dostoyevsky and his theology". Journal of the Grace Evangelical Society. Grace Evangelical Society. 10:19. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Wilson, Colin 1956. The outsider. London: Gollancz, p175 (Pan edition).

- ↑ "Russian literature". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

In The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov Dostoyevsky, who is generally regarded as one of the supreme psychologists in world literature, sought to demonstrate the compatibility of Christianity with the deepest truths of the psyche.

- ↑ Nabokov, Vladimir. “Lectures on Russian Literature”. Harcourt, 1981, p. 104

- ↑ Kaufmann, Walter (ed) 1989. Existentialism: from Dostoyevsky to Sartre. Penguin Books, p. 12. ISBN 0452009308

- ↑ Greig, Ian 1973. Subversion: propaganda, agitation and the spread of people's war. Letchworth, Hertfordshire: Tom Stacey, p8. ISBN 0-85468-495-6

Other websites

| Wikisource has original writing related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |