Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (/ræˈspjuːtɪn/;[1] 22 January [O.S. 9 January] 1869 – 30 December [O.S. 17 December] 1916) was a Russian peasant, and a mystical faith healer.[2] He was not a monk who lived in a monastery, but a religious pilgrim. In 1904 he arrived in the capital St Petersburg. The Tsar and Tsarina talked many times with Rasputin and asked for advice as he became their spiritual guide.

Grigori Rasputin | |

|---|---|

Григорий Ефимович Распутин | |

Grigori Rasputin | |

| Born | Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin 22 January 1869 |

| Died | 30 December 1916 (aged 47) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Cause of death | Murder by gunshots and drowning |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Spouse(s) | Praskovia Fedorovna Dubrovina |

| Children | Dmitri (1895–1937) Maria (1898–1977) Varvara (1900–1925) |

| Parent(s) | Efim Rasputin Anna Parshukova |

Life

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin was born a peasant in the small village of Pokrovskoye, along the Tura River in the Tobolsk Governorate (now Tyumen Oblast) in the Russian Empire. He was named for St. Gregory of Nyssa, whose feast was celebrated on 10 January.

Rasputin had a lot of influence over Tsarina Alexandra, the wife of Tsar Nicholas II. Alexandra believed that Rasputin was the answer to her worries.[2] Her only son, Tsarevich Alexei, the heir to the throne was very sick. He had hemophilia. It caused heavy bleeding and pain in his groin and legs each time he fell. Rasputin calmed the boy and the parents. She believed Rasputin was the only person who could heal her son with his prayers.[2]

Because of this, the Tsar and his family began to trust Rasputin more with important decisions on politics. Rasputin did not support the Tsar when he decided to lead his country into World War I. In July 1914, during a stay in his home village, he was stabbed in his belly by a female conspirator Khioniya Guseva. After seven weeks, Rasputin recovered and went back to the capital. There he lived with his two daughters, who went to school in the capital.

In August 1915, the Tsar decided to lead the country's army himself, and replace his cousin Grand Duke Nikolai. Almost nobody supported him, except Alexandra and Rasputin. Many Russian politicians and nobles became very worried about Rasputin's influence. While the Tsar was at the front, Alexandra and Rasputin took many bad decisions. They proposed to the Tsar, who was extremely shy and weak-willed, the replacement of several ministers with ones that supported peace. At the end of 1916, Imperial Russia was in a chaotic state. In the big cities there was almost nothing to eat or heat. All the trains were used to supply the army. Some politicians in the parliament decided to attack Alexandra and Rasputin. Their goal was to go on with the war, even though there were heavy losses and a lack of weapons and ammunition.

Death

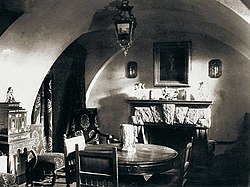

In the night of 30 December 1916, Rasputin was led into the Yusupov palace's basement. He was offered wine. When he got drunk, he was shot twice by Prince Felix Yusupov. One shot went into his right kidney and then into his spine. He climbed some stairs and staggered out of the palace through a back door. Rasputin was shot again in the courtyard. To be sure he was dead, he was shot in the forehead at close range. Grand Duke Dmitri drove the conspirators to the Neva River. There they dropped his body from the bridge.[2] In the meantime, Prince Felix had killed his favorite dog, to cover the blood in the courtyard. A few days later Rasputin's body, completely frozen, was found stuck in the ice. The next day the corpse was buried in a park next to the Alexander Palace. After the February Revolution, the new leaders decided to dig up his body to prevent it from becoming a place of worship; and eventually burned it.

Grigori Rasputin Media

Makary, Bishop Theofan and Rasputin, 1909

Alexandra Feodorovna with her children, Rasputin and the nurse Maria Ivanova Vishnyakova, 1908

Rasputin with his daughter Maria (rightmost), in his St. Petersburg apartment, 1911

Felix Yusupov, husband of Princess Irina Aleksandrovna Romanova, the Tsar's niece, 1914

The wooden Bolshoy Petrovsky Bridge from which Rasputin's body was thrown into the Malaya Nevka River

References

- ↑ "Rasputin". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Maria Aprelenko (2011). "Prominent Russians: Grigory Rasputin". Russiapedia. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

Bibliography

- Buchanan, George (1923). My mission to Russia and other diplomatic memories. Cassell and Co., Ltd., London, New York. OL 6656274M.

- Fuhrmann, Joseph T., ed. (1999). The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra. April 1914-March 1917. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30511-0.

- Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (2013). Rasputin, the untold story (illustrated ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-1-118-17276-6.

- Hoare, Samuel (1930). The Fourth Seal. William Heinemann Limited.

- Kerensky, Alexander (1965). Russia and History's turning point. Duell, Sloan and Pearce, New York. OCLC 237312.

- King, Greg (1994). The Last Empress. The Life & Times of Alexandra Feodorovna, tsarina of Russia. A Birch Lane Press Book. ISBN 1559722118.

- Lieven, Dominic (1993). Nicholas II: Twilight of the Empire. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312143796.

- Massie, Robert K (2004) [originally in New York: Atheneum Books, 1967]. Nicholas and Alexandra: An Intimate Account of the Last of the Romanovs and the Fall of Imperial Russia (Common Reader Classic Bestseller ed.). United States: Tess Press. ISBN 1-57912-433-X. OCLC 62357914.

- Miliukov, Paul N. (1978). The Russian Revolution, Vol. I. The Revolution Divided: Spring 1917. Academic International Press.

- Moe, Ronald C. (2011). Prelude to the Revolution: The Murder of Rasputin. Aventine Press. ISBN 978-1593307127.

- Moynahan, Brian (1997). Rasputin. The saint who sinned. Random House. ISBN 0306809303.

- Nelipa, Margarita (2010). The Murder of Grigorii Rasputin. A Conspiracy That Brought Down the Russian Empire. Gilbert's Books. ISBN 978-0-9865310-1-9.

- Out of My Past: Memoirs of Count Kokovtsov. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1553-9.

- Pares, Bernard (1939). The Fall of the Russian Monarchy. A Study of the Evidence. Jonathan Cape. London.

- Purichkevitch, Vladimir (1923). "Comment j'ai tué Raspoutine". J. Povolozky & Cie. In English: [1]

- Radzinsky, Edvard (2000). Rasputin: The Last Word. St Leonards, New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-529-4. OCLC 155418190. Originally in London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Rappaport, Helen (2014). Four Sisters. The Lost lives of the Romanov Grand Duchesses. Pan Books..

- Rasputin, Maria (1934). My father.

- Shelley, Gerard (1925). The Speckled Domes. Episodes of an Englishman's life in Russia. Duckworth London.

- Smith, Douglas (2016). Rasputin. MacMillan, London. ISBN 978-1-4472-4584-1.

- Spiridovich, Alexander (1935). Raspoutine (1863–1916). Payot, Paris.

- Vyrubova, Anna (1923). Memories of the Russian Court. [2]

- Welch, Frances (2014). Rasputin: A Short Life. Croydon, South London, Great Britain: Short Books and CPI Group (UK) Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78072-153-8.

- Wilson, Collin (1964). Rasputin and the Fall of the Romanovs. New York, Farrar, Straus.