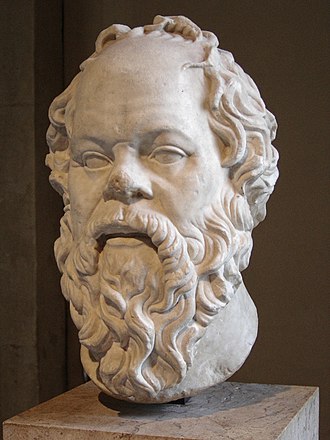

Socrates

Socrates (399 BC-470 BC) was one of the most famous Greek philosophers. He showed how argument, debate, and discussion could help men to understand difficult issues. Most of the issues he dealt with only seemed to be political. They were actually moral questions about how life should be lived.[1] Socrates had so much influence that philosophers before him are called the Presocratic philosophers.[2]

Enemies

Socrates made enemies, three of whom brought charges against him. Socrates was tried for his life in 399 BC, found guilty, and put to death by drinking common hemlock (a herbal poison).[1] The story of his trial and death is described by Plato in a book called the Apologia.

Socrates and Plato

Most of what we know about Socrates comes from the works of Plato, who was his student. Socrates lived in the Greek city of Athens. His method of teaching was to have a dialogue with individual students. They would propose some point of view, and Socrates would question them, asking what they meant. He would pretend "I don't know anything; I'm just trying to understand what it is you are saying", or words that basically meant that. This is now called the Socratic method of teaching.

Reputation

Socrates is sometimes called the "father of Western philosophy". This is because in the discussions he uncovered some of the most basic questions in philosophy, questions which are still discussed today. Some of the people he taught came to be important and successful, like Plato, Xenophon, and Alcibiades.

The life of Socrates

Socrates never wrote anything. All of what we know about Socrates is from what other people wrote about him. Our main source of what we know about Socrates is from the writings of his student, Plato. Some of Plato's dialogues, such as the Crito and the Phaedo, are loosely based on fact. They are not written records, but artistic re-creation of Socrates in action.[1]

Xenophon also wrote about Socrates. Aristophanes, a person who wrote brilliant satirical comedies, wrote about him in play called The Clouds. Socrates was an easy target for satire. He walked barefoot, and with a swagger. Sometimes he stood in a trance for hours.[1]p8 In The Clouds Socrates is a crazy person who tries to scam people out of their money. Plato wrote that Socrates taught for free.

We do not know if Plato's description of Socrates is accurate or not. That is called the 'Socratic problem'. While a lot of what Plato wrote about Socrates is accepted by historians, some believe that Plato (who saw Socrates as a hero) portrayed Socrates as a greater man than he actually was. Some think that Plato was using the character of Socrates as a tool to express his own opinions rather than to accurately write about Socrates. This is what makes Socrates such a mysterious historical figure. Plato's dialogues are works of art, finely written. The general view is that they are based on reality, but no doubt adjusted for the purpose of writing.

Biographical details

Socrates' father was a sculptor, and his mother was a midwife who helped women give birth to children.[1] He may have been a stonemason like his father, and Plato wrote that he served in the Athenian army as a hoplite (heavy infantry). We know he was influenced by an older philosopher, Archelaus, and that he talked with anyone who had interesting ideas in Athens, but beyond that nothing is known.

Socrates was about 50 when he married a much younger woman, Xanthippe. They had three children together. Socrates made complaints about his wife, but no one knew if he was telling the truth.

It is said that one of Socrates' friends went to ask the oracle at Delphi if there was anyone wiser than Socrates in Athens. The oracle said that there was no wiser person. The oracle was well known for saying things that were ambiguous or unclear. It did not say that Socrates was the wisest, just that there was no person wiser.

After being puzzled by this, Socrates finally decided that his wisdom lay in knowing that he was ignorant. His attempts to show the citizens that some of their ideas were nonsense might help explain his unpopularity. In Plato's works, Socrates says he knows nothing, but can draw out other people's ideas just as his mother helped other women to give birth.

The death of Socrates

The accusations

In 399 BC, when Socrates was an old man, three citizens—Meletus, Anytus and Lycon—brought charges against Socrates. A trial was held. In ancient Athens the procedure was quite different from the present day. There was a jury of 500 men drawn from the citizens. Both the accusers and the defendant had to make speeches in person to the jury. Guilt or innocence was by majority vote. There was no preset penalty if the verdict was 'guilty'. Both the accuser and the defendant would make speeches proposing what the penalty should be. Again, a vote was taken.[1]p17

There were two charges against him. The general theme was that Socrates was a menace to society. The first charge was of heresy, disbelief in the Gods. It was probably meant to cause prejudice amongst the jurymen. Actually, Socrates observed all the correct procedures of the religion of his times. The charge had been used successfully against another philosopher, Anaxagoras.[1]p17

The second charge was piety. What was meant by this? Apparently, this was not about his personal relationship with his pupils. It was about the way he was thought to influence their political views. His circle had included a number of right-wing aristocrats whose ideas were now rejected by most citizens. The brilliant Alcibiades, once a great leader of Athens, was now seen as a traitor.[1]p17

The trial

Crito, a friend of Socrates, illegally paid the prison guards to allow Socrates to escape. Socrates, however, decided not to escape. When Socrates was put on trial, he gave a long speech to defend himself against the claims made by the Athens government.

We have Plato's version of how Socrates defended himself, in the Apologia. It starts:

- "I do not know what effect my accusers have had upon you, gentlemen, but for my own part I was carried away by them; their arguments were so convincing. On the other hand, scarcely a word of what they said was true".[1]p19

The sentence

When Socrates was asked to propose his punishment, Socrates said that the government should give him free dinners for the rest of his life for all the good that he did for society. The court held a vote between giving Socrates a fine to pay or putting him to death. The verdict was that Socrates was to be put to death.

Death of Socrates

Plato on Socrates' trial and death

There are several dialogues by Plato which deal directly with the trial of Socrates and the period up to his death. They are, in order of the events:

- Apologia, or The Apology. This deals in particular with Socrates' defence at his trial. It is regarded as accurate in substance, and perhaps in detail.

- Crito. This deals with the month between his trial and his death. In particular, Socrates explains to his friend Crito why he is not going to escape, or permit his friends to bribe the jailor.

- Phaedo. This is a later work. It is written as if by an eye-witness of the last day of Socrates' life. In the work, Phaedo of Elias reports to a group of friends on what Socrates said on his last day. This is called a "reported dialogue" or one dialogue inside another. The Phaedo is longer than the other two works.

The ideas of Socrates

Socrates helped people to see what was wrong with their ideas. Sometimes they liked this, sometimes they were not happy or grateful. He said that he, Socrates, was not wise, but that he "knew that he knew nothing." Since other people think they know something, but no one really knows anything, Socrates claimed he knew more than anyone else. He said that people who do bad things do so because they do not know any better.

People think that Socrates was a good man because he did no harm, except he asked questions about everything. However, during his life many people thought he was a bad person, because he asked those questions and because he made young people unhappy about their lives.

Someone once wrote that Socrates said that "A life that was not examined was not worth living". This means that someone must think about their own life and its purpose. Some people believe that most humans are happier if they do not think too much about their life.

Socrates also taught that many people can look at something and not truly see it. He asked questions about the meaning of life and goodness. These are still very important questions. Much of philosophy (love of wisdom) is about these things.

Legacy

Socrates is seen by some people as a martyr, since he willingly died to support the idea that knowledge and wisdom are very important to our lives.

Socrates is known as one of the most important philosophers in history. He is often described as the father of Western philosophy. He did not start Western philosophy, but he had a big influence on it. Before Socrates, philosophy was mainly about mathematics and answering questions about our natural world. Socrates expanded on that and added questions about ethics, politics, and epistemology to philosophy.

Socrates Media

The Death of Socrates, by Jacques-Louis David (1787). Socrates was visited by friends in his last night in prison. His discussion with them gave rise to Plato's Crito and Phaedo.[3]

Ruins of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, where Pythia was sited. The Delphic aphorism Know thyself was important to Socrates, as evident in many Socratic dialogues by Plato, especially Apology.[4]

Henri Estienne's 1578 edition of Euthyphro, parallel Latin and Greek text. Estienne's translations were heavily used and reprinted for more than two centuries.[5] Socrates's discussion with Euthyphro still remains influential in theological debates.[6]

Alcibiades Receiving Instruction from Socrates, a 1776 painting by François-André Vincent, depicting Socrates's daimon[7]

Depiction of Socrates in a manuscript by Al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik

The statue of Socrates outside the National Library of Uruguay, Montevideo

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Plato. The last days of Socrates. Translation and introduction by Hugh Tredennick. Penguin, London

- ↑ Guthrie W.K.C. 1962. A history of Greek philosophy. Cambridge University Press, London. Volume 1 The earlier presocratics and the pythagoreans. Volume 2 The presocratic tradition from Parmenides to Democritus.

- ↑ Guthrie 1972, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Ahbel-Rappe 2011, p. 144.

- ↑ Ausland 2019, pp. 686–687.

- ↑ McPherran 2011, p. 117.

- ↑ Lapatin 2009, p. 146.