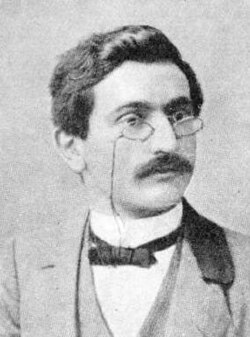

Emanuel Lasker

Emanuel Lasker (24 December 1868 – 11 January 1941) was a German chess player, mathematician, and philosopher who was World Chess Champion for 27 years.

| Emanuel Lasker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Full name | Emanuel Lasker |

| Country | Germany |

| Born | December 24, 1868 Berlinchen, Prussia |

| Died | January 11, 1941 (aged 72) New York City, United States |

| World Champion | 1894–1921 |

In his prime Lasker was one of the most dominant champions, and he is generally regarded as one of the strongest players ever. He finally lost the title to Capablanca in 1921.[1]

Lasker demanded high fees for playing matches and tournaments, which aroused some criticism. He had seen how Steinitz's life had ended in poverty, and was determined to avoid this fate.

The conditions which Lasker demanded for World Championship matches in the last ten years of his reign were controversial, and prompted attempts to define rules for championship matches.

Lasker was also a talented mathematician, and his Ph.D. thesis is regarded as one of the foundations of modern algebra. He was a first-class contract bridge player and wrote about this and other games, including Go and his own invention, Lasca.

Life and career

Early years (1868–1894)

Emanuel Lasker was the son of a Jewish cantor. At the age of eleven he was sent to Berlin to study mathematics, where he lived with his brother Berthold, eight years his senior, who taught him how to play chess. To supplement their income Emanuel Lasker played chess and card games for small stakes, especially at the Café Kaiserhof.[2]

In 1890 he finished third in Graz, then shared first prize with his brother Berthold in a tournament in Berlin. In spring 1892, he won two tournaments in London, the second and stronger of these without losing a game. At New York 1893, he won all thirteen games, one of the few times in chess history that a player has achieved a perfect score in a significant tournament.[3]p81 [4][5]

His record in matches was equally impressive: at Berlin in 1890 he drew a short play-off match against his brother Berthold; and won all his other matches from 1889 to 1893, mostly against top-class opponents: Curt von Bardeleben 1889; Jacques Mieses 1889; Henry Edward Bird 1890; Berthold Englisch 1890; Joseph Henry Blackburne 1892, without losing a game; Jackson Showalter 1892–1893; and Celso Golmayo Zúpide 1893.

In 1892 Lasker founded the first of his chess magazines, The London Chess Fortnightly, which was published from August 15, 1892 to July 30, 1893. In the second quarter of 1893 there was a gap of ten weeks between issues, allegedly because of problems with the printer.[6] Shortly after its last issue Lasker traveled to the USA, where he spent the next two years.

Lasker challenged Siegbert Tarrasch, who had won three consecutive international tournaments, to a match. Tarrasch haughtily declined, stating that Lasker should first prove his mettle by attempting to win one or two major international events.[7]p31

Chess competition (1894–1918)

Match against Steinitz

Rebuffed by Tarrasch, Lasker challenged the reigning World Champion Wilhelm Steinitz to a match for the title.[7]p31 Initially Lasker wanted to play for US $5,000 a side, but the final figure was $2,000. The final combined stake of $4,000 would be worth over $495,000 at 2006 values.[8]

The match was played in 1894, at venues in New York, Philadelphia, and Montreal. Steinitz had previously declared he would win without doubt, so it came as a shock when Lasker won the first game. Steinitz responded by winning the second, and was able to maintain the balance through the sixth. However, Lasker won all the games from the seventh to the eleventh, and Steinitz asked for a week's rest. When the match resumed, Steinitz looked in better shape and won the 13th and 14th games. Lasker struck back in the 15th and 16th, and Steinitz was unable to compensate for his losses in the middle of the match. Hence Lasker won convincingly with ten wins, five losses and four draws.[9] Lasker thus became the second recognized World Chess Champion, and confirmed his title by beating Steinitz even more convincingly in their re-match in 1896–1897 (ten wins, five draws, and two losses).

Match against Schlechter

Lasker won first prizes at very strong tournaments in St. Petersburg 1895–1896, Nuremberg 1896, London 1899, Paris 1900. As time passed, there arose two great players, Akiba Rubinstein and Capablanca. Both deserved a match for the world championship, but as it turned out, the chance came to another fine player, Carl Schlechter.

Lasker arranged the World Chess Championship match against Schlechter in January–February 1910. Schlechter was a modest man, who was generally unlikely to win the major chess tournaments by his peaceful inclination, his lack of aggressiveness and his willingness to accept most draw offers from his opponents (about 80% of his games finished by a draw).[10]p404

The conditions of the match are still debatable, because they were never published.[3]p357 Some claim that Schlechter accepted especially unfavourable conditions. Giffard says he would need to finish two points ahead of Lasker to be declared the winner of the match, and he would need to win a revenge match to be declared World Champion.[10]p404 This opinion is not proven.

The match was originally meant to consist of 30 games, but when it became obvious that there were insufficient funds (Lasker demanded a fee of 1,000 marks per game played), the number of games was reduced to ten.

In the fifth game Lasker had a big advantage, but made a mistake which cost him the game. Schlechter was now a point ahead. The score before the last game was 5–4 for Schlechter. In the tenth game Schlechter tried to win and took a clear advantage, but he missed a win on his 35th move, and finished by losing.[10]p406 Hence the match was a draw and Lasker remained World Champion.

At St. Petersburg 1914 he overcame a 1½ point deficit to finish ahead of the rising stars Capablanca and Alexander Alekhine.

Match against Capablanca

In January 1920 Lasker and José Raúl Capablanca signed an agreement to play a World Championship match in 1921, noting that Capablanca was not free to play in 1920.[11]

The match was played in March–April 1921. After four draws, the fifth game saw Lasker blunder with Black in an equal ending. Capablanca's solid style allowed him to easily draw the next four games, without taking any risks. In the tenth game, Lasker as White failed to create the necessary activity and Capablanca reached a superior ending, which he duly won. The eleventh and fourteenth games were also won by Capablanca, and Lasker resigned the match.[10]

Some commentators attributed the result to Lasker's being in mysteriously poor form.[12] On the other hand Vladimir Kramnik thought that Lasker played quite well and the match was an "even and fascinating fight" until Lasker blundered in the last game, and explained that Capablanca was twenty years younger, a slightly stronger player, and had more recent competitive practice.

Later life

After winning the New York 1924 chess tournament (1½ points ahead of Capablanca) and finishing second at Moscow in 1925 (1½ points behind Efim Bogoljubow, ½ point ahead of Capablanca), he effectively retired from serious chess.

In 1926 Lasker wrote Lehrbuch des Schachspiels, which he re-wrote in English in 1927 as Lasker's Manual of Chess.[13] He also wrote books on other games of mental skill: Encyclopedia of games (1929) and Das verständige Kartenspiel (1929);[14] English translation in the same year. Both these books posed a problem in the mathematical analysis of card games.[15] Brettspiele der Völker ("Board games of the nations" 1931) had 30 pages about Go and a section about a game he had invented in 1911, Lasca.[16] Das Bridgespiel "The Game of Bridge" was published in 1931.[17] Lasker became an expert bridge player, representing Germany at international events in the early 1930s, and a registered teacher of the Culbertson system.[18]

In October 1928 Emanuel Lasker's brother Berthold died.[7]p266

In spring 1933 Adolf Hitler started a campaign of discrimination and intimidation against Jews, depriving them of their property and citizenship. Lasker and his wife Martha, who were both Jewish, left Germany the same year.[7]p268 [3]p218 After a stay in England, in 1935 they were invited to live in the USSR by Nikolai Krylenko, the Commissar of Justice responsible for the Moscow show trials and also Sports Minister. Krylenko was an enthusiastic supporter of chess. In the USSR, Lasker renounced his German citizenship and received Soviet citizenship.[19] He took up residence in Moscow, and was given a post at Moscow's Institute for Mathematics, and a post of trainer of the USSR national team.[20] Lasker returned to competitive chess to make some money, finishing fifth in Zürich 1934; third in Moscow 1935 behind Mikhail Botvinnik and Salo Flohr and ahead of Capablanca and other masters; sixth in Moscow 1936 and seventh equal in Nottingham 1936. His performance in Moscow 1935 at age 66 was hailed as "a biological miracle".[21]

Stalin's Great Purge started at about the same time the Laskers arrived in the USSR. In August 1937, Martha and Emanuel Lasker decided to leave the Soviet Union, and they moved, via the Netherlands, to the United States (first Chicago, next New York) in October 1937.[19]

In the following year Emanuel Lasker's patron, Krylenko, was purged by Stalin. Lasker tried to support himself by giving chess and bridge lectures and exhibitions, as he was now too old for serious competition. In 1940 he published his last book, The community of the future, in which he proposed solutions for serious political problems, including anti-Semitism and unemployment. Lasker died of a kidney infection in New York on 11 January 1941, at the age of 72.[22][23]

Emanuel Lasker Media

David Hilbert encouraged Lasker to obtain a PhD in mathematics.

References

- ↑ Forster R. Hansen S. and Negele M. (eds) 2009. Emanuel Lasker: Denker, Weltenbürger, Schachweltmeister. Ekzelsior, Berlin.

- ↑ Tyle L.B., ed. (2002). UXL Encyclopedia of world biography. U·X·L. ISBN 0787664650.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hooper, David and Whyld, Kenneth (1992). The Oxford Companion to Chess. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Soltis, Andrew (2002). Chess Lists, 2nd ed. McFarland & Company. pp. 81–83. ISBN 0786412968.

- ↑ Sunnucks, Anne (1970). The Encyclopaedia of Chess. St. Martin's Press. p. 76.

- ↑ Lasker, Emanuel. The London Chess Fortnightly (PDF). Moravian Chess.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Hannak J. (1959). Emanuel Lasker: the life of a chess master. Simon & Schuster. p. 31.

- ↑ Using incomes for the adjustment factor, as the outcome depended on a few months' hard work by the players; if prices are used for the conversion, the result is over $99,000 - see "Six ways to compute the relative value of a U.S. Dollar amount, 1774 to present". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2008-05-30. However, Lasker later published an analysis showing that the winning player got $1,600 and the losing player $600 out of the $4,000, as the backers who had bet on the winner got the rest: "From the Editorial Chair". Lasker's Chess Magazine. 1. January 1905. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- ↑ Kažić B.M. (1974). International Championship Chess: a complete record of FIDE events. Pitman. p. 212. ISBN 0-273-07078-9.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Giffard, Nicolas (1993). Le guide des échecs (in French). Éditions Robert Laffont.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Winter, Edward. "How Capablanca became world champion". ChessHistory. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ↑ Golombek, H. (1959). "On the way to the World Championship". In Golombek, H. (ed.). Capablanca's hundred best games of chess. G. Bell & Sons. p. 59.

- ↑ Lasker, Emanuel (1960) [1927, 2nd edition 1932]. Lasker's Manual of Chess (reprint ed.). Dover. ISBN 0486206408.

- ↑ Means "Sensible cardplay"

- ↑ Johan Wăstlund (September 5, 2005). "A solution of two-person single-suit whist" (PDF). The Electronic Journal of Combinatorics. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2008.

- ↑ "About Lasca — a little-known abstract game". Human–Computer Interface Research. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09.

- ↑ "Chess and Bridge". ChessHistory.

- ↑ Culbertson, Ely (1940). The strange lives of one man. Chicago. pp. 552–553.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Litmanowicz, Władysław; Giżycki, Jerzy (1986). Szachy od A do Z. Wydawnictwo Sport i Turystyka Warszawa. ISBN 83-217-2481-7. 83-217-2745-X (2. N-Z).

- ↑ Weinstein, Boris Samoilovich (1981). Myslitel (Thinker). Fizkultura i sport. pp. 104/5.

- ↑ Reuben Fine (1976). The world's great chess games. Dover. p. 51. ISBN 0-486-24512-8.

- ↑ Winter, Edward. "5076. Lasker's last words". ChessHistory. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ Landsberger, K. (2002). The Steinitz Papers: letters and documents of the first World Chess Champion. McFarland. p. 295. ISBN 0786411937.

Other websites

- The 7th game of the world championship match. Lasker (white) v Schlechter (black). [1] Of this game Heidenfeld said (in Draw!, Allen & Unwin 1982) "It is probably the most profound game ever played in a world championship match".