Influenza pandemic of 1918

The Influenza pandemic of 1918 (commonly known as the Spanish flu) lasted for nearly three years, from March 1918 to December 1920.[1] About 500 million[1] people were infected across the world, which had at the time a population of 1.80 billion people. The pandemic spread to remote Pacific Islands and the Arctic. It killed 50 million[2] to 100 million people.[3] This was three to five percent of the world's population at the time.[3] It was one of the greatest natural disasters in human history.[1][4][5][6]

To keep up morale, wartime censors reduced reports of illness and mortality in Germany, Britain (United Kingdom), France, and the United States.[7][8] Papers could report the epidemic's effects in neutral Spain (such as the grave illness of King Alfonso XIII). This situation created the false impression of Spain being especially hard-hit.[9] It also resulted in the nickname Spanish flu.[10]

Often, influenza outbreaks kill young people, or the elderly, or those patients that are already weakened. This was not the case for the 1918 pandemic, which killed mainly healthy young adults. Modern research, using virus taken from the bodies of frozen victims, has concluded that the virus kills through a cytokine storm (overreaction of the body's immune system). The strong immune reactions of young adults ravaged the body. But, the weaker immune systems of children and middle-aged adults caused fewer deaths among those groups.[11]

There is not enough historical and epidemiological data to show where the pandemic started.[1] The pandemic may be a cause of the outbreak of encephalitis lethargica in the 1920s.[12]

Another swine flu pandemic had happened in the 21st century that turned out to be new strain of H1N1. The outbreak began in Mexico and then the United States and to the world.

Gallery

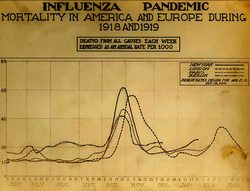

Number of deaths in New York City, Berlin, Paris, and London (Museum of Health & Medicine, Washington), c. 1918–1919

Two American Red Cross nurses demonstrated treatment practices during the influenza pandemic of 1918.

Albertan farmers wore masks to protect themselves from the flu.

Policemen wearing masks provided by the American Red Cross in Seattle, 1918

A street car conductor in Seattle in 1918 refusing to allow passengers aboard who are not wearing masks

Red Cross workers remove a flu victim in St. Louis, Missouri (1918)

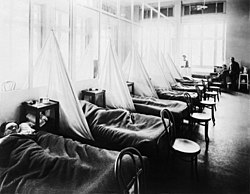

Influenza ward at Walter Reed Hospital during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918–1919

Burying flu victims, North River, Newfoundland and Labrador (1918)

Cavalry memorial on the hill Lueg, memory of the Bernese cavalrymen victims of the 1918 flu pandemic; Emmental, Bern, Switzerland

Influenza Pandemic Of 1918 Media

Advertisement in The Times, 28 June 1918 for Formamint tablets to prevent "Spanish influenza"

Seattle policemen wearing cloth face masks handed out by the American Red Cross during the Spanish flu pandemic, December 1918

An article naming wealthy socialites for violating city law banning public gatherings, Chicago Tribune, October 19, 1918. Named violators include Joan Pinkerton Chalmers, daughter of Pinkertons private police founder Allan Pinkerton.

American Expeditionary Force flu patients at U.S. Army Camp Hospital no. 45 in Aix-les-Bains, France, 1918

Mars, god of war, plays a "tragic game of football" with a skeleton personification of the Spanish flu, November 1918

American Red Cross nurses tend to flu patients in temporary wards set up inside the Oakland Municipal Auditorium

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Taubenberger JK; Morens DM 2006 (2006). "1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics" (PDF). Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (1): 15–22. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050979. PMC 3291398. PMID 16494711. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 2, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Knobler S, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon S (ed.). "1: The Story of Influenza". The threat of pandemic influenza: are we ready? Workshop summary (2005). Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. pp. 60–61.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)[dead link] - ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Historical Estimates of World Population". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. July 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ↑ Patterson KD; Pyle GF 1991 (1991). "The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. Johns Hopkins University. 65 (1): 4–21. PMID 2021692.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Billings, Molly (June 1997). "The Influenza Pandemic of 1918". virus.stanford.edu. Stanford University. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ↑ Johnson NP; Mueller J 2002 (2002). "Updating the accounts: Global mortality of the 1918–1920 "Spanish" influenza pandemic". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 76 (1): 105–15. doi:10.1353/bhm.2002.0022. PMID 11875246. S2CID 22974230.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Valentine, Vikki (August 20, 2008). "Origins of the 1918 Pandemic: the case for France". NPR.org. National Public Radio (NPR). Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ↑ Anderson, Susan (August 29, 2006). "Analysis of Spanish flu cases in 1918–1920 suggests transfusions might help in bird flu pandemic". EurekAlert.org: The Global Source for Science News. American College of Physicians. Archived from the original on November 25, 2011. Retrieved Feb 4, 2016.

- ↑ Barry, John M. (2004). The Great Influenza: the epic story of the greatest plague in history. Viking Penguin. p. 171. ISBN 0-670-89473-7.

- ↑ Galvin, John (July 31, 2007). "Spanish Flu Pandemic: 1918". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ↑ Tisoncik JR; Korth MJ; et al. 2012 (2012). "Into the Eye of the Cytokine Storm". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 76 (1): 16–32. doi:10.1128/MMBR.05015-11. PMC 3294426. PMID 22390970.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Vilensky JA; Foley P; et al 2007 (2007). "Children and encephalitis lethargica: A historical review". Pediatric Neurology. Elsevier. 37 (2): 79–84. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.04.012. PMID 17675021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)