Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder. People with this disorder often show abnormal social behavior and fail to recognize what is real. Common symptoms include strange beliefs, unclear or confused thinking and language, hearing voices, reduced social activity, reduced expression of feelings and inactivity. Diagnosis is based on observing the person and what he or she says about experiences such as hearing voices. Problems have to last for at least six months before the person gets a diagnosis.[1]

| Schizophrenia | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| File:Artistic view of how the world feels like with schizophrenia - journal.pmed.0020146.g001.jpg A painting often used to help explain what a person with schizophrenia experiences. | |

| ICD-10 | F20. |

| ICD-9 | 295 |

| OMIM | 181500 |

| DiseasesDB | 11890 |

| MedlinePlus | 000928 |

| eMedicine | med/2072 emerg/520 |

| MeSH | F03.700.750 |

Meaning

The word schizophrenia comes from two Greek words that mean to split and mind because there is a 'split' between what's going on in their minds and what's happening in reality. A person with schizophrenia does not change between different personalities: they have only one.[2] The condition in which a person has multiple personalities is dissociative identity disorder. There are no medical tests that can be used to say if a person has schizophrenia or not, so getting a diagnosis depends on which list of symptoms are used. It also depends on the doctor or psychologist who talks to the person. The lists of symptoms include wording like " Disorganized speech present for a significant portion of time". It is difficult to agree on what exactly "disorganized speech" is and how disorganized it has to be. It is also difficult to agree on what "significant portion of time" means. The result is that two doctors or psychologists trying to make a diagnosis may often disagree. One will say that the person is schizophrenic and the other will say he is not. [3]

Is it schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia has many different symptoms, and not everyone with schizophrenia has all of them. For this reason, some scientists think that schizophrenia is several separate disorders that have some of the same symptoms. These scientist claim that the research done on schizophrenia is not accurate since different researchers mean different things when they use the word "schizophrenia" in scientific studies.

Many medications may also give schizophrenia symptoms. The most common ones are antidepressants and ADHD medication. If a person has taken anti-vomiting medication for some time and suddenly stops, he or she may get schizophrenia symptoms. Hundreds of medications have schizophrenia symptoms as rare side effects. Drugs such as LSD, amphetamines, magic mushrooms and cocaine may cause schizophrenia symptoms. [4]

As medical illnesses, and the treatment with certain drugs can show symptoms very similar to that of schizophrenia, it is important to rule out these two factors, so that no false diagnosis is done. For this reason, the person should have a thorough medical exam to rule out problems like lack of vitamin B12, lack of magnesium, sodium and several other substances needed in the body, sleep disorders, stroke or brain tumors, and too high or too low metabolism. There are over hundred medical conditions that may give the same symptoms as schizophrenia.

Delusions and hallucinations

People with Schizophrenia often have delusions or hallucinations. In that context, a schizophrenic delusion is a belief that is very different from what other people in the persons sub-culture believe. Hallucinations are usually impressions of hearing voices that other people don't hear. These voices often say negative things to the person. Many people can hear voices like this without being schizophrenic, for instance right before falling asleep. This is called hypnagogic hallucinations. The brain can not tell them apart from normal sounds that are heard. This is not yet fully understood by science.

Risk factors

There are many risk factors that may cause a person to develop schizophrenia. They include trauma and genetics: the disorder runs in families. Having a schizophrenic parent may be very stressful (environment) and there may be genes that influence the development of schizophrenia. It is very easy to show that trauma, such as sexual abuse, increases the risk, but 40 years of search for genes has not found anything that has been confirmed by independent research groups. [5] Also environmental factors like as viruses, oxygen deprivation and poor nutrition which may affect a developing unborn baby.

Hope

People with schizophrenia may also have other mental health disorders, like depression, anxiety and drug abuse.[6] They often have problems functioning in society, and have difficulty maintaining stable employment. However there are a number of people with schizophrenia whoget well and have earned college degrees and professional careers such as Elyn. R. Saks, a law professor at the University of Southern California and a published author. 8 of 10 get well from schizophrenia in a family treatment called "Open dialog" in Finland. In developing countries, where doctors use less drugs, 2 of 3 get well from schizophrenia. In western countries where medications are used as treatment, 1 of 3 get well, but many suffer from drug side effects such as diabetes, overweight, and brain damage.[7]

Treatment

Treatment of schizophrenia may include medication to help treat the symptoms, different types of psychotherapy, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and various rehabilitation therapies, such as cognitive remediation therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT, is a talk therapy that focuses on helping the person to think about their strange ideas (delusions) in more realistic ways.

The therapist may design a behavioral experiment for paranoia that will help the person to find out for instance if there really are cameras everywhere in the house. When it comes to hallucinations, cognitive therapy focuses on normalizing: many people hear voices without being stressed, and we all hear voices in the form of thoughts, it is just that you hear them a bit more clearly than most people.[8]

Official guidelines

The British national guidelines for treatment (NICE) suggest the following treatments: Check for reactions to traumatic experiences, decide together with a doctor about using medication, taking into account the side effect risk of getting diabetes, becoming seriously overweight, getting brain damage (tardive dyskinesia, 5% risk pr year), men growing , and feelings described as inner torture(akathesia). The guidelines warn against using more than one antipsychotic drug at the same time. Both for people who are at risk for getting schizophrenia and for people who have got it, they recommend cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT and family therapy. Getting support from people who have become well from schizophrenia is also strongly recommended. [9] In a family oriented treatment program in Finland, Open Dialog, 8 out of 10 people with Schizophrenia get well with no medication or very limited drug use, often only anxiety medication.[10]

Symptoms

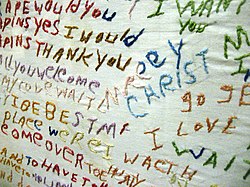

This is one example of the disorganized thinking caused by the disorder.

The symptoms of schizophrenia fall into three main categories: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and cognitive symptoms.[12]

- Positive symptoms

- Positive symptoms are thoughts, behaviors, or anything experienced by the senses that are not shared by others - like hearing voices that are not really there. They are called 'positive' not because they are good but because they are "added on". These symptoms may include having strange thoughts that do not make sense (delusions),disorganized thoughts and speech, and feeling, hearing, seeing, smelling, or tasting things that do not exist (hallucinations).[13] Positive symptoms often respond to drug treatment[14] and cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT.[8] Stopping anti psychotic drugs or anti-vomiting too quickly may also cause these symptoms.[15]

- Negative symptoms

- Negative symptoms are thoughts, behaviors or emotions normally present in a healthy person that a person with a mental disorder has less of or may not have at all, they are 'minus' these. The sign for minus is -; it is also the sign for the word "negative". Negative symptoms includes a 'flat affect'; having a blank inexpressive look on the face and/or a monosyllabic speech spoken in a slow monotone, few gestures, lack of interest in anything including other people, inability to act spontaneously or feel pleasure. These problems are also side effects of antipsychoctic drugs. They may also be symptoms of many medical problems such as too low metabolism [15]

- Cognitive symptoms (or cognitive deficits)

- Cognitive symptoms are problems with attention, certain types of memory, concept of time, and the ability to plan and organize. Cognitive deficits caused by schizophrenia can also be difficult to recognize as part of the disorder. They are the most disabling of the symptoms because cognitive problems affect everyday functioning.These problems may also be side effects of anti psychotic drugs, antidepressants, sleeping medication and anti-anxiety drugs.[15]

Causes

A combination of what has happened to a person and the person’s genes may play a role in the development of schizophrenia.[16][17] People who have family members with schizophrenia and who experienced a brief period of psychotic symptoms have a 20- to 40-percent chance of being diagnosed one year later. This may be both the result of stressful events because of the family member and possibly a genetic effect. [18]

Inherited factors

It is difficult to know if schizophrenia is inherited because it is hard to find out what comes from genes and what comes from the environment.[19] Those who have a parent, a brother or sister with schizophrenia have a higher risk of developing schizophrenia. The risk is even higher if you have an identical twin with schizophrenia.[17] This may seem to show that Schizophrenia is inherited. However, it may be the stress of living with a schizophrenic family member that is traumatic. Identical twins are much closer and are treated much more in the same way, and this may be the reason why one of them gets schizophrenia more often if the other has it. Dr Jay Joseph has found many problems with the scientific studies of inheriting schizophrenia, including false reporting of results. Joseph also claims that 40 years of the search for the schizophrenia gene has not found a single gene that independent reseach groups have confirmed. [20] [21]

Environmental factors

There are may environmental risk factors factors for schizophrenia such as drug use, stress before birth and in some cases exposure to infectious disease.[16] In addition, living in a city during childhood or as an adult has been found to double the risk of schizophrenia .[16][17] This is true even after taking into account drug use, ethnicity, and the size of one’s social group.[22] Other factors that play an important role include whether the person feels socially isolated, as well as social adversity, racial discrimination, failures in family functioning, unemployment, and poor housing conditions.[17][23] There is evidence that childhood experiences of abuse or trauma are risk factors for developing schizophrenia later in life.[24]

Substance abuse Several drugs have been linked with the development of schizophrenia and the abuse of certain drugs and can cause symptoms like those of schizophrenia.[17][17][25] About half of those people who have schizophrenia use too much drugs or alcohol, possibly to deal with depression, anxiety, boredom, or loneliness.[26] Frequent marijuana use may double the risk of serious mental illness and schizophrenia.[27]

Smoking

More people with schizophrenia smoke than the general population; it is estimated that at least 60% to as much as 90% of people with schizophrenia smoke. Recent research suggests that cigarette smoking may be a risk factor for developing schizophrenia. Smoking also reduces the effects and side effects of anti psychotic drugs, and this may be one of the reasons for the high smoking rate. Patients taking anti psychotic drugs die up to 20 years earlier than others, possibly because the medication makes them overweight, gives diabetes and makes them smoke.

Pre-birth factors

Factors such as lack of oxygen, infection, or stress and lack of healthy foods in the mother during pregnancy, might result in a slight increase in the risk of schizophrenia later in life.[16] People who have schizophrenia are more likely to have been born in winter or spring (at least in the northern half of the world). This might relate to increased rates of exposures to viruses before birth.[17] This difference is about 5 to 8 percent.[28]

Brain structure

Some people who have schizophrenia have differences in their brain structure compared to those who do not have the disorder. These differences are often in the parts of the brain that manage memory, organization, emotions, the control of impulsive behavior, and language.[29] Among these structural differences, are a reduction in brain volume in the frontal cortex and temporal lobes, and problems within the corpus callosum, the band of nerve fibers which connects the left side and the right side of the brain. People with schizophrenia also tend to have enlarged lateral and third ventricles. The ventricles are spaces within the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid.[30]

- Brain wiring

The human brain has 100 billion neurons, each one of these neurons are connected to many other neurons. One neuron may have as many as 20,000 connections; there is between 100 trillion and 500 trillion neural connections in the adult human brain. There are many different parts or 'regions' of the brain. To complete a task -like recalling a memory - usually more than one region of the brain is involved, and they are connected by neural networks which is like the brain's wiring. It is believed that there are problems with the brain's wiring in schizophrenia.

Diagnosis

The DSM-IV-TR or the ICD-10 criteria are used to determine whether a person has schizophrenia.[16] These criteria use the self-reported experiences of the person and reported abnormalities in the behavior of the person, followed by a clinical assessment. A person can be determined to have the disease only if the symptoms are severe.[17]

| Criteria for diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|

|

European countries usually use ICD-10 criteria, while the United States and the rest of the world usually use the Diagnostic and Staticians Manual (DSM).[31] DSM diagnostic criteria is divided into three categories:

Subtypes The DSM-IV-TR contains five subtypes of schizophrenia, although the developers of the next version of the DSM, DSM-5, recommend that these subtypes be dropped:[32][33]

The ICD-10 defines two additional subtypes:[33]

| ||

Differential diagnosis

There are various medical conditions, other psychiatric conditions and drug abuse related reactions that may mimic the symptoms of schizophrenia. For example delirium can cause visual hallucinations, or an unpredictable changing levels of consciousness. Schizophrenia occurs along with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), a disorder in which a person becomes obsessed with certain ideas or actions. However, separating the obsessions of OCD from the delusions of schizophrenia can be difficult.[34]

Prevention

There is no clear evidence that treating schizophrenia with ani psychotic drugs early is effective.[35] The British NICE guidelines reccommend CBT talk therapy for all people at risk.[36] In recent research, 76 patients at risk for schizophrenia were divided in two groups. One group got omega3 for 3 months and the other got a dummy pill (food oil). After 12 months only 4.9% of the omega 3 group had got schizophrenia compared to 27.5% in the other group. [37] There is some evidence which shows that early treatment with drugs improves short term outcomes for people who have a serious episode of mental illness. These measures show little benefit five years later.[16] Attempting to prevent schizophrenia in the pre-onset phase with anti psychotic drugs is of uncertain benefit and so is not recommended (as of 2009).[38] Prevention is difficult because there are no reliable way to find out in advance who will get schizophrenia.[39]

Management

The treatment of schizophrenia is based upon the phase of the illness the person is in. There are three treatment phases.

- Acute Phase

The goals of treatment during the acute phase of treatment, defined by an acute psychotic episode, are to prevent harm, control disturbed behavior, reduce the severity of psychosis and associated symptoms (e.g., agitation, aggression, negative symptoms, affective symptoms), determine and address the factors that led to the occurrence of the acute episode, effect a rapid return to the best level of functioning, develop an alliance with the patient and family, formulate short- and long-term treatment plans, and connect the patient with appropriate aftercare in the community

- Stabilization Phase

During the stabilization phase, the goals of treatment are to reduce stress on the patient and provide support to minimize the likelihood of relapse, enhance the patient’s adaptation to life in the community, facilitate continued reduction in symptoms and consolidation of remission, and promote the process of recovery. If the patient has improved with a particular medication regimen, continuation of that regimen and monitoring are recommended for at least 6 months.

- Stable Phase

The goals of treatment during the stable phase are to ensure that symptom remission or control is sustained, that the patient is maintaining or improving his or her level of functioning and quality of life, that increases in symptoms or relapses are effectively treated, and that monitoring for adverse treatment effects continues. Regular monitoring for adverse effects is recommended. For most persons with schizophrenia in the stable phase, psychosocial interventions are recommended as a useful adjunctive treatment to pharmacological treatment and may improve outcomes [I]. Antipsychotic medications substantially reduce the risk of relapse in the stable phase of illness and are strongly recommended

Medication

The first-line psychiatric treatment for schizophrenia is antipsychotic medication,[36] which can reduce the positive symptoms in about seven to fourteen days. However, medication fails to improve negative symptoms or problems in thinking significantly.[40][41] Many antipsychotics are Dopamine antagonists. High concentrations of Dopamine are thought to be the cause of hallucinations and delusions. For this reason blocking Dopamine reception helps against hallucinations and delusions. The guidelines warn against using more than one antipsychotic drug at the same time.

Some reviews of research sponsored by the makers of antipsychotic drugs claim that about 40 to 50 percent of people have a good response to medication, 30 to 40 percent have a partial response, and 20 percent have an unsatisfactory response (after 6 weeks on two or three different drugs).[40] Other research from The British Journal of Psychiatry were more negative and claimed that "the clinical relevance of antipsychotics is in fact limited". This study included 22 428 patients and 11 antipsychotic drugs. [42] A drug called clozapine is an effective treatment for people who respond poorly to other drugs, but clozapine can lower the white blood cell count in 1 to 4 percent of people who take it. This is a serious side effect.[16][17][43]

For people who are unwilling or unable to take drugs regularly, injectable long-acting preparations of antipsychotics can be used.[44] When used in combination with mental and social interventions, such preparations can help people to continue their treatment.[44]

Psychosocial therapies

Numerous mental and social interventions can be useful in treating schizophrenia. Such interventions include various types of therapy,[45] community-based treatments, supported employment, skills training, token economic interventions, and mental interventions for drug or alcohol use and weight management.[46] Family therapy or education, which addresses the whole family system of an individual, might reduce a return of symptoms or the need for hospitalizations.[45] There is growing evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (also known as “talk therapy”) .[47][48]

The British national guidelines for treatment (NICE) suggest the following treatments: . Both for people who are at risk for getting schizophrenia and for people who have got it, they recommend cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT and family therapy. Getting support from people who have become well from schizophrenia is also strongly recommended. [49] In a family oriented treatment program in Finland, Open Dialog, 8 out of 10 people with Schizophrenia get well with no medication or very limited drug use, often only anxiety medication.[50]

Outlook

Schizophrenia has great human and economic costs.[16] The condition results in a decreased life expectancy of 12 to 15 years, primarily because of its association with being overweight, not exercising, and smoking cigarettes. An increased rate of suicide plays a lesser role.[16] These differences in life expectancy increased between the 1970s and 1990s.[51]

Schizophrenia is a major cause of disability, with active psychosis ranked as the third-most-disabling.[52] Approximately three-fourths of people with schizophrenia have ongoing disability with symptoms that keep coming back.[40] Some people do recover completely and others function well in society.[53] Most people with schizophrenia live independently, with community support.[16] In people with a first episode of serious mental symptoms, 42 percent have a good long-term outcome. Thirty-five percent of the people have an intermediate outcome. Twenty-seven percent of the people have a poor outcome.[54] Outcomes for schizophrenia appear better in the developing world than in the developed world,[55] although that conclusion has been questioned.[56][57]

The suicide rate of people who have schizophrenia is estimated to be about 4.9 percent, most often occurring in the period following the first appearance of symptoms or the first hospital admission.[58] 20 to 40 percent try to kill themselves at least once.[59][60]

Schizophrenia and smoking have shown a strong association in studies worldwide.[61][62] Use of cigarettes is especially high in individuals who have schizophrenia, with estimates ranging from 80 to 90 percent of these people being regular smokers, as compared to 20 percent of the general population.[62] Those individuals who smoke tend to smoke heavily and smoke cigarettes with a high nicotine content.[60]

Research continues on Schizophrenia. In Spring of 2013, genetics associations were shown between five major psychiatric disorders: autism, ADHD, bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia per recent study.[63][64] In the summer of 2013, for the first time brain tissue development was been replicated in three dimensions by scientists cloning a human "mini-brain" using stem cells. This could help with schizophrenia and autism neurological research. [65]

Likelihood

As of 2011, schizophrenia affects around 0.3% to 0.7% of people,[16] or 24 million people worldwide,[66] at some point in their lives. More men are affected than women: the number of males with the disorder is 1.4 times greater than that of females. Schizophrenia usually appears earlier in men.[17] For males the symptoms usually start from 20 to 28 years of age, and in females it is 26 to 32 years of age.[67] Symptoms that start in childhood,[68] middle or old age are much rarer.[69] Despite the received wisdom that schizophrenia occurs at similar rates worldwide, its rate of likelihood varies across the world,[70] within countries,[71] and at the local level.[72] The disorder causes approximately 1% of worldwide disability adjusted life years (in other words, years spent with a disability).[17] The rate of schizophrenia varies depending on how it is defined.[16]

History

Accounts of a schizophrenia-like syndrome are rare before the 19th century. Detailed case reports from 1797 and 1809, are regarded as the earliest cases of the disorder.[74] Schizophrenia was first described as a distinct syndrome affecting teenagers and young adults by Bénédict Morel in 1853, termed démence précoce (literally 'early dementia'). The term dementia praecox was used in 1891 by Arnold Pick in a case report of a psychotic disorder. In 1893 Emil Kraepelin introduced a new distinction in the classification of mental disorders between dementia praecox and mood disorder (termed manic depression and including both unipolar and bipolar depression). Kraepelin believed that dementia praecox was primarily a disease of the brain,[75] and a form of dementia, different from other forms of dementia such as Alzheimer's disease which usually happen later in life.[76]

Eugen Bleuler coined the term ”schizophrenia”, which translates roughly as "split mind",[77] in 1908. The word was intended to describe the separation of functioning between personality, thinking, memory, and perception.[78] Bleuler realized that the illness was not a dementia because some of his patients improved rather than got worse.

In the early 1970s, the criteria for determining schizophrenia were the subject of numerous controversies. Schizophrenia was diagnosed far more often in the United States than in Europe.[79] This difference was partly the result of looser criteria for determining whether someone had the condition in the United States, where the DSM-II manual was used. In Europe, the ICD-9 manual was used. A 1972 study, published in the journal Science, concluded that the diagnosis of schizophrenia in the United States was often unreliable.[80] These factors resulted in the publication of the DSM-III in 1980 with a stricter and more defined criteria for the diagnosis.[81]

Society and culture

Negative social judgment has been identified as a major obstacle in the recovery of people who have schizophrenia.[82]

In 2002, the term for schizophrenia in Japan was changed from “Seishin-Bunretsu-Byō” 精神分裂病 (“mind-split-disease”) to “Tōgō-chō-shō” 統合失調症 (“integration disorder”), in an attempt to reduce feelings of shame or embarrassment.[83] The idea that the disease is caused by multiple factors (not just one mental cause) inspired the new name. The change increased the percentage of people who were informed of the diagnosis from 37 percent to 70 percent over three years.[84]

In the United States in 2002, the cost of schizophrenia, including direct costs (people who were not hospitalized, people who were hospitalized, medicines, and long-term care) and non-healthcare costs (law enforcement, reduced workplace productivity, and unemployment), was estimated to be $62.7 billion.[85]

The book “A Beautiful Mind” and the film of the same name are about the life of John Forbes Nash, an American mathematician and Nobel Prize winner who has schizophrenia. The movie The Soloist is based on the life of Nathaniel Ayers, a gifted musician who dropped out of the prestigious Julliard School, in New York City after the symptoms of schizophrenia began. He later became homeless in Los Angeles, California, in the notorious Skid Row section.

References

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 5–25. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ↑ Berrios G.E.; Porter, Roy (1995). A history of clinical psychiatry: the origin and history of psychiatric disorders. London: Athlone Press. ISBN 0-485-24211-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 5–25. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ↑ http://www.pdr.net/resources/pdr-ebook/

- ↑ Joseph, J. (2003). The Gene Illusion: Genetic Research in Psychiatry and Psychology under the Microscope. PCCS Books. ISBN 1-898059-47-0.

- ↑ Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, Castle DJ (2009). "Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia". Schizophr Bull. 35 (2): 383–402. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn135. PMC 2659306. PMID 19011234.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America, Crown, April 13, 2010, ISBN 978-0-307-45241-2

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Cognitive Therapy of Schizophrenia David G. Kingdon, Douglas TurkingtonGuilford Press, 2005

- ↑ Smith T, Weston C, Lieberman J (2010). "Schizophrenia (maintenance treatment)". Am Fam Physician. 82 (4): 338–9. PMID 20704164.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑

{{cite journal}}: Empty citation (help) - ↑ Face Recognition: New Research. Ed. Katherine B. Leeland Nova Publishers (2008) p.49 ISBN 9781604564662

- ↑ David Sue, Derald Wing Sue, Stanley Sue. Understanding Abnormal Behavior Wadsworth Publishing; 9 edition (2008) p.361 ISBN 0547154410

- ↑ Kneisl C. and Trigoboff E.(2009). Contemporary Psychiatric- Mental Health Nursing. 2nd edition. London: Pearson Prentice Ltd. p. 371

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 9780890420256. p. 299

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Breggin, P. (2008) Brain-Disabling Treatments in Psychiatry: Drugs, Electroshock, and the Psychopharmaceutical Complex Springer Publishing Co, New York

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):635–45. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. PMID 19700006.

- ↑ 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 17.10 Picchioni MM, Murray RM (2007). "Schizophrenia". BMJ. 335 (7610): 91–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.39227.616447.BE. PMC 1914490. PMID 17626963.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Drake RJ, Lewis SW (2005). "Early detection of schizophrenia". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 18 (2): 147–50. doi:10.1097/00001504-200503000-00007. PMID 16639167.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ O'Donovan MC, Williams NM, Owen MJ (2003). "Recent advances in the genetics of schizophrenia". Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 Spec No 2: R125–33. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg302. PMID 12952866.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Joseph, J. (2003). The Gene Illusion: Genetic Research in Psychiatry and Psychology under the Microscope. PCCS Books. ISBN 1-898059-47-0.

- ↑ http://www.madinamerica.com/2013/03/the-trouble-with-twin-studies/

- ↑ Van Os J (2004). "Does the urban environment cause psychosis?". British Journal of Psychiatry. 184 (4): 287–288. doi:10.1192/bjp.184.4.287. PMID 15056569.

- ↑ Selten JP, Cantor-Graae E, Kahn RS (2007). "Migration and schizophrenia". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 20 (2): 111–115. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328017f68e. PMID 17278906.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Larkin W, Read J (2008). "Childhood trauma and psychosis: evidence, pathways, and implications". J Postgrad Med. 54: 287–293. PMID 18953148.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Larson, Michael (2006-03-30). "Alcohol-Related Psychosis". eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- ↑ Gregg L, Barrowclough C, Haddock G (2007). "Reasons for increased substance use in psychosis". Clin Psychol Rev. 27 (4): 494–510. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.004. PMID 17240501.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Leweke FM, Koethe D (2008). "Cannabis and psychiatric disorders: it is not only addiction". Addict Biol. 13 (2): 264–75. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00106.x. PMID 18482435.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Yolken R. (2004). "Viruses and schizophrenia: a focus on herpes simplex virus". Herpes. 11 (Suppl 2): 83A–88A. PMID 15319094.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Kircher, Tilo and Renate Thienel (2006). "Functional brain imaging of symptoms and cognition in schizophrenia". The Boundaries of Consciousness. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 302. ISBN 0444528768.

- ↑ Green MF (2006). "Cognitive impairment and functional outcome in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (Suppl 9): 3–8. PMID 16965182.

- ↑ Jakobsen KD, Frederiksen JN, Hansen T; et al. (2005). "Reliability of clinical ICD-10 schizophrenia diagnoses". Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 59 (3): 209–12. doi:10.1080/08039480510027698. PMID 16195122.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Work Groups (2010)Proposed Revisions – Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders" (pdf). World Health Organization. p. 26.

- ↑ Bottas A (April 15, 2009). "Comorbidity: Schizophrenia With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder". Psychiatric Times. 26 (4).

- ↑ Marshall M, Rathbone J (2006). "Early intervention for psychosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD004718. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004718.pub2. PMID 17054213.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2009-03-25). "Schizophrenia: Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-11-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|home=ignored (help) - ↑

{{cite journal}}: Empty citation (help) - ↑ de Koning MB, Bloemen OJ, van Amelsvoort TA; et al. (2009). "Early intervention in patients at ultra high risk of psychosis: benefits and risks". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 119 (6): 426–42. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01372.x. PMID 19392813.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, McGorry P (2007). "The empirical status of the ultra high-risk (prodromal) research paradigm". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 33 (3): 661–4. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm031. PMC 2526144. PMID 17470445.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Smith T, Weston C, Lieberman J (2010). "Schizophrenia (maintenance treatment)". Am Fam Physician. 82 (4): 338–9. PMID 20704164.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA (2008). "Schizophrenia, "Just the Facts": what we know in 2008 part 1: overview" (PDF). Schizophrenia Research. 100 (1–3): 4–19. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.022. PMID 18291627.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|formt=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑

{{cite journal}}: Empty citation (help) - ↑ Wahlbeck K, Cheine MV, Essali A (2007). "Clozapine versus typical neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. (2): CD000059. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000059. PMID 10796289.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 44.0 44.1 McEvoy JP (2006). "Risks versus benefits of different types of long-acting injectable antipsychotics". J Clin Psychiatry. 67 Suppl 5: 15–8. PMID 16822092.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Pharoah F, Mari J, Rathbone J, Wong W (2010). "Family intervention for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12: CD000088. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000088.pub3. PMID 21154340.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS; et al. (2010). "The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements". Schizophr Bull. 36 (1): 48–70. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp115. PMID 19955389.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Lynch D, Laws KR, McKenna PJ (2010). "Cognitive behavioural therapy for major psychiatric disorder: does it really work? A meta-analytical review of well-controlled trials". Psychol Med. 40 (1): 9–24. doi:10.1017/S003329170900590X. PMID 19476688.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Jones C, Cormac I, Silveira da Mota Neto JI, Campbell C (2004). "Cognitive behaviour therapy for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD000524. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000524.pub2. PMID 15495000.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Smith T, Weston C, Lieberman J (2010). "Schizophrenia (maintenance treatment)". Am Fam Physician. 82 (4): 338–9. PMID 20704164.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑

{{cite journal}}: Empty citation (help) - ↑ Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J (2007). "A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time?". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 64 (10): 1123–31. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. PMID 17909124.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ustun TB (1999). "Multiple-informant ranking of the disabling effects of different health conditions in 14 countries". The Lancet. 354 (9173): 111–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07507-2. PMID 10408486.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Warner R (2009). "Recovery from schizophrenia and the recovery model". Curr Opin Psychiatry. 22 (4): 374–80. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832c920b. PMID 19417668.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Menezes NM, Arenovich T, Zipursky RB (2006). "A systematic review of longitudinal outcome studies of first-episode psychosis". Psychol Med. 36 (10): 1349–62. doi:10.1017/S0033291706007951. PMID 16756689.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Isaac M, Chand P, Murthy P (2007). "Schizophrenia outcome measures in the wider international community". Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 50: s71–7. PMID 18019048.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Cohen A, Patel V, Thara R, Gureje O (2008). "Questioning an axiom: better prognosis for schizophrenia in the developing world?". Schizophr Bull. 34 (2): 229–44. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm105. PMC 2632419. PMID 17905787.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Burns J (2009). "Dispelling a myth: developing world poverty, inequality, violence and social fragmentation are not good for outcome in schizophrenia". Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg). 12 (3): 200–5. PMID 19894340.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM (2005). "The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination". Archives of General Psychiatry. 62 (3): 247–53. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.247. PMID 15753237.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Carlborg A, Winnerbäck K, Jönsson EG, Jokinen J, Nordström P. Suicide in schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(7):1153–64. doi:10.1586/ern.10.82. PMID 20586695.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 9780890420256. p. 304

- ↑ De Leon J, Diaz FJ (2005). "A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors". Schizophrenia research. 76 (2–3): 135–57. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.010. PMID 15949648.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Keltner NL, Grant JS (2006). "Smoke, Smoke, Smoke That Cigarette". Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 42 (4): 256. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2006.00085.x. PMID 17107571.

- ↑ http://www.scienceworldreport.com/articles/5266/20130228/five-very-different-major-psych-disorders-shared-genetics.htm

- ↑ doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61345-8

- ↑ http://news.msn.com/science-technology/scientists-grow-mini-human-brains-from-stem-cells

- ↑ "Schizophrenia". World Health Organization. 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ↑ Castle D, Wessely S, Der G, Murray RM (1991). "The incidence of operationally defined schizophrenia in Camberwell, 1965–84". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 159: 790–4. doi:10.1192/bjp.159.6.790. PMID 1790446.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kumra S, Shaw M, Merka P, Nakayama E, Augustin R (2001). "Childhood-onset schizophrenia: research update". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 46 (10): 923–30. PMID 11816313.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Hassett Anne, et al. (eds) (2005). Psychosis in the Elderly. London: Taylor and Francis. p. 6. ISBN 1841843946.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G; et al. (1992). "Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures. A World Health Organization ten-country study". Psychological Medicine Monograph Supplement. 20: 1–97. doi:10.1017/S0264180100000904. PMID 1565705.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C; et al. (2006). "Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center AeSOP study". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (3): 250–8. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.250. PMID 16520429.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C; et al. (2007). "Neighbourhood variation in the incidence of psychotic disorders in Southeast London". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 42 (6): 438–45. doi:10.1007/s00127-007-0193-0. PMID 17473901.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Thomas Bewle. Madness to Mental Illness: A History of the Royal College of Psychiatrists RCPsych Publications; 1 edition (2008) p.52 ISBN 1904671357

- ↑ Heinrichs RW (2003). "Historical origins of schizophrenia: two early madmen and their illness". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 39 (4): 349–63. doi:10.1002/jhbs.10152. PMID 14601041.

- ↑ Kraepelin E, Diefendorf AR (1907). Text book of psychiatry (7 ed.). London: Macmillan.

- ↑ Hansen RA, Atchison B (2000). Conditions in occupational therapy: effect on occupational performance. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-30417-8.

- ↑ Kuhn R (2004). tr. Cahn CH. "Eugen Bleuler's concepts of psychopathology". History of Psychiatry. 15 (3): 361–6. doi:10.1177/0957154X04044603. PMID 15386868.

- ↑ Stotz-Ingenlath G (2000). "Epistemological aspects of Eugen Bleuler's conception of schizophrenia in 1911" (PDF). Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy. 3 (2): 153–9. doi:10.1023/A:1009919309015. PMID 11079343.

- ↑ Wing JK (1971). "International comparisons in the study of the functional psychoses". British Medical Bulletin. 27 (1): 77–81. PMID 4926366.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Rosenhan D (1973). "On being sane in insane places". Science. 179 (4070): 250–8. doi:10.1126/science.179.4070.250. PMID 4683124.

- ↑ Wilson M (1993). "DSM-III and the transformation of American psychiatry: a history". American Journal of Psychiatry. 150 (3): 399–410. PMID 8434655.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Maj, Mario and Sartorius N. (15 September 1999). Schizophrenia. Chichester: Wiley. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-471-99906-5.

- ↑ Kim Y, Berrios GE (2001). "Impact of the term schizophrenia on the culture of ideograph: the Japanese experience". Schizophr Bull. 27 (2): 181–5. PMID 11354585.

- ↑ Sato M (2004). "Renaming schizophrenia: a Japanese perspective". World Psychiatry. 5 (1): 53–55. PMC 1472254. PMID 16757998.

- ↑ Wu EQ (2005). "The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 (9): 1122–9. PMID 16187769.

{{Spoken Wikipedia|Schizophren