Nonverbal communication

Nonverbal communication (NVC) uses signals without words. Language is not the only way to communicate, there are other means. Much nonverbal communication is unconscious: it happens without people thinking about it.

Nonverbal communication may use gestures and touch, body language or posture, facial expression and eye contact. NVC may be done by clothing and hairstyles. Dance is also a type of nonverbal communication.

Speech has nonverbal elements known as paralanguage. These include voice quality, emotion and speaking style, rhythm, intonation and stress. Likewise, written texts have nonverbal elements such as handwriting style, spatial arrangement of words, or the use of emojis and emoticons, such as :) and 😊

Nonverbal communication has three main aspects: the situation where it takes place, the communicators, and their behavior during the interaction.[1]p7 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities defines nonverbal communication also one of communication.[2]

Meaning of verbal & non-verbal

Verbal means 'the use of words'. Thus, vocal sounds which are not words are nonverbal. Examples are grunts, or singing a wordless note. Sign languages and writing are understood as verbal communication, as both make use of words – although like speech, paralinguistic elements do occur alongside nonverbal messages. Nonverbal communication can occur through any sensory channel – sight, sound, smell, touch or taste. Nonverbal communication is important because:

"When we speak (or listen), our attention is focused on words rather than body language. But our judgement includes both. An audience is simultaneously processing both verbal and nonverbal cues. Body movements are not usually positive or negative in and of themselves; rather, the situation and the message will determine the appraisal".[3]p4

Functions of nonverbal communication

Spoken language is often used for communicating information about external events, but non-verbal codes are more used in interpersonal relationships.[4] According to Argyle, there are five primary functions of nonverbal bodily behavior in human communication:[5]

- To express emotions

- To express interpersonal attitudes

- To accompany speech: it helps speakers manage their conversation.

- To present one’s personality

- To perform rituals (such as greetings)

Paralanguage

Paralanguage is the study of nonverbal cues of the voice. Various acoustic properties of speech such as tone, pitch and accent, collectively known as prosody, can all give off nonverbal cues. Paralanguage may change the meaning of words.

The linguist George L. Trager developed a classification of voice set, voice qualities, and vocalization.[6]

- The voice set is the context in which the speaker is speaking. This can include the situation, gender, mood, age and a person's culture.

- The voice qualities are volume, pitch, tempo, rhythm, articulation, resonance, nasality, and accent. They give each individual a unique 'voice print'.

- Vocalization has three subsections: characterizers, qualifiers and segregates.

- Characterizers are emotions expressed while speaking, such as laughing, crying, and yawning.

- A qualifier is the style of delivering a message – for example, yelling "Hey stop that!", as opposed to whispering "Hey stop that".

- Vocal segregates, such as "uh-huh", tell the speaker that the listener is actually listening.

Visual communication

Clothes

Clothes, and fashion generally, send messages. We judge others by what we see, at least when we first meet them. Fashion is a reflection of the time and place. The styles show as much about history and the time period as any history book. Clothes often show what people think, and how they live. Fashion is a nonverbal statement. It reflects our time, our beliefs and sometimes our religion.

Body language

Body language means how your body is held: the stance. It tends to show your attitude (state of mind) to what is going on round you. Others pick up the signs in a flash.

Eye gaze

Eye contact can indicate interest, attention, and involvement.[1]p10 Gaze includes looking while talking, looking while listening, amount of gaze, and frequency of glances, patterns of fixation, pupil dilation, and blink rate.[5]p153

Emotions

Showing strong emotions is powerful communication which is immediately understood. Many of the signals are the same in all cultures, as Darwin showed.[7] Examples of strong emotions shown visually are:

These are listed in order of clarity. No one mistakes anger or fear, but more subtle emotions may sometimes be missed by the onlooker.

Touch

Touch, including handshake and hug, is classic nonverbal communication. It is perhaps the most intimate (closest) thing one person can do to another. What it means depends on the context. Here is a short-list of what we may do when we touch another person:

Arts

Most of the arts are forms of non-verbal communication:

The animal world

Animals other than humans do not have our kind of language, but they make use of non-verbal communication. With many, scent plays a greater role in their communication. Also, social animals can get to understand the meaning of tone of voice, and even understand key words. Say "walkies!" to the family dog...[8] With animals which are social and intelligent, humans can have a genuine relationship. In general, that means animals which are mammals or perhaps pet parrots. Communication of the non-verbal kind is strongly developed in mammals, and mammals are mostly social animals.

Many animals recognise each other's alarm signals (cross-species communication).[9] Indeed, animal communication of one kind or another is almost universal amongst vertebrates.[10]

Nonverbal CommunicationParalanguage Media

Understanding each other through hand and eye expression; seen in a street near the bell tower of Xi'an, China

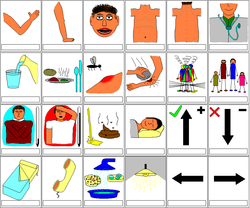

Symbol table for non-verbal communication with patients

Charles Darwin wrote The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals in 1872.

Information about the relationship and affect of these two skaters is communicated by their body posture, eye gaze and physical contact.

A high five is an example of communicative touch.

Related pages

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Knapp, Mark L. & Hall, Judith A. 2007. Nonverbal communication in human interaction. 5th ed, Wadsworth. ISBN 0-15-506372-3

- ↑ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Article 2

- ↑ Givens D.B. 2000. Body speak: what are you saying? Successful Meetings, 51.

- ↑ Argyle, Michael et al. 1970. The communication of inferior and superior attitudes by verbal and non-verbal signals. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 9: 222-231.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Argyle, Michael. 1988. Bodily communication. 2nd ed, Madison. ISBN 0-416-38140-5

- ↑ Floyd K. & Guerrero, L.K. 2006. Nonverbal communication in close relationships. Erlbaum, Mahwah N.J.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles 1872. The expression of emotions in man and animals. 200th anniversary edition edited by Paul Ekman. HarperCollins 1998. ISBN 975-0-00-638734-3

- ↑ Hotchner, Tracie 2005. The Dog Bible: everything your dog wants you to know. Penguin. ISBN 9781440623080

- ↑ Fichtel C. 2004. Reciprocal recognition of sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi verreauxi) and redfronted lemur (Eulemur fulvus rufus) alarm calls. Animal Cognition 7:45–52.

- ↑ Bradbury J.W. and S.L. Vehrencamp. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer.

Further reading

- Andersen, Peter 2004. The complete idiot's guide to body language. Alpha Publishing. ISBN 978-1592572489

- Demarais A. & White V. 2004. First impressions. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0553803204

- Driver J. 2010. You say more than you think. New York, NY: Crown.

- Pease B. & Pease A. 2004. The definitive book of body language. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

+{{{1}}}−{{{2}}}