Watermill

A watermill is an engine that uses a water wheel or turbine to drive a mechanical process such as flour or lumber production, or metal shaping (rolling, grinding or wire drawing). A watermill that only generates electricity is more usually called a hydroelectric plant.

History

China

In 31 AD, a Chinese engineer named Du Shi (Wade-Giles: Tu Shih) "invented the first water-powered bellows. This was a complicated machine with gears, axles, and levers that was powered by a waterwheel,".[1] This invention aided the forging of cast iron smelted from the blast furnace. More extensive descriptions appear in literature of the 5th century.

Greece and Rome

The ancient Greeks and Romans used the technology. In the 1st century BC, the Greek epigrammatist Antipater of Thessalonica was the first to make a reference to the waterwheel. He praised it for its use in grinding grain and the reduction of human labor.

The Romans used both fixed and floating water wheels and introduced water power to other countries of the Roman Empire. So-called 'Greek Mills' used water wheels with a vertically mounted shaft. A "Roman Mill" features a horizontally-mounted shaft. Greek style mills are the older and simpler of the two designs, but only operate well with high water velocities and with small diameter millstones. Roman style mills are more complicated as they require gears transmit the power from a shaft with a horizontal axis to one with a vertical axis. An example of a Roman era watermill would be the early 4th century site at Barbegal in southern France, where 16 overshot waterwheels were used to power an enormous flour mill.

The Cistercian Order built huge mill complexes all over Western Europe during the medieval period.

Medieval Europe

In a 2005 survey the scholar Adam Lucas identified the following first appearances of various industrial mill types in Western Europe. Noticeable is the preeminent role of France in the introduction of new innovative uses of waterpower.

| First Appearance of Various Industrial Mills in Medieval Europe, AD 770-1443 [2] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of mill | Malt mill | Fulling mill | Tanning mill | Forge mill | Tool-sharpening mill | Hemp mill | Bellows | Sawmill | Ore-crushing mill | Blast furnace | Cutting and slitting mill |

| Date | 770 | 1080 | ca. 1134 | ca. 1200 | 1203 | 1209 | 1269, 1283 | ca. 1300 | 1317 | 1384 | 1443 |

| Country | France | France | France | England, France | France | France | Slovakia, France | France | Germany | France | France |

Operation of a watermill

Typically, water is diverted from a river or impoundment or mill pond to a turbine or water wheel, along a channel or pipe (variously known as a flume, head race, mill race, leat, leet,[3] lade (Scots) or penstock). The force of the water's movement drives the blades of a wheel or turbine, which in turn rotates an axle that drives the mill's other machinery. Water leaving the wheel or turbine is drained through a tail race, but this channel may also be the head race of yet another wheel, turbine or mill. The passage of water is controlled by sluice gates that allow maintenance and some measure of flood control; large mill complexes may have dozens of sluices controlling complicated interconnected races that feed multiple buildings and industrial processes.

Watermills can be divided into two kinds, one with a horizontal waterwheel on a vertical axle, and the other with a vertical wheel on a horizontal axle. The oldest of these were horizontal mills in which the force of the water, striking a simple paddle wheel set horizontally in line with the flow turned a runner stone balanced on the rynd which is atop a shaft leading directly up from the wheel. The bedstone does not turn. The problem with this type of mill arose from the lack of gearing; the speed of the water directly set the maximum speed of the runner stone which, in turn, set the rate of milling.

Types of watermills

- Gristmills grind grains into flour. These were undoubtedly the most common kind of mill.

- Fulling mills or Walkmills were used for a finishing process on cloth (see also fulling).

- Blade mills were used for sharpening newly made blades.

- Sawmills cut timber into lumber

- Barking mills stripped bark from trees for use in tanneries

- Spoke mills turned lumber into spokes for carriage wheels.

- At the beginning of the industrial revolution, cotton mills were usually powered by a water wheel.

- Carpet mills for making rugs were sometimes water-powered.

- Textile mills for weaving cloth were sometimes water-powered.

- Powder mills for making black powder or smokeless powder were sometimes water-powered.

- Blast Furnaces, finery forges, slitting mills, and tinplate works were until the introduction of the steam engine invariably water powered and were sometimes called iron mills.

- Prior to the introduction of the cupola (a reverberatory furnace), lead was usually smelted in smelt mills.

- Paper mills used water not only for motive power but also in large quantities in the manufacturing process.

Watermill Media

Watermill of Braine-le-Château, Belgium (12th century)

Interior of the Lyme Regis watermill, UK (14th century)

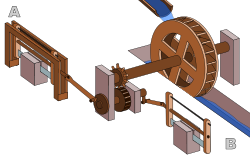

Model of a Roman water-powered grain mill described by Vitruvius. The millstone (upper floor) is powered by an undershot waterwheel by the way of a gear mechanism (lower floor)

Scheme of the Roman Hierapolis sawmill, the earliest known machine to incorporate the mechanism of a crank and connecting rod

German ship mills on the Rhine, around 1411

A Northern Song era (960–1127) water-powered mill for dehusking grain with a horizontal wheel

An Afghan water mill photographed during the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–1880). The rectangular water mill has a thatched roof and traditional design with a small horizontal mill-house built of stone or perhaps mud bricks.

A watermill in Tapolca, Veszprem County, Hungary

Related pages

References

- ↑ Woods 51

- ↑ Adam Robert Lucas, “Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe“, Technology and Culture, Vol. 46, (Jan. 2005), pp. 1-30 (17)

- ↑ Webster's New Twentieth Century Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged (1952) states: leet, n. A leat; a flume. [Obs.]

Further reading

- Woods, Michael and Mary (2000). Ancient Machines: From Wedges to Waterwheels. Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

Other websites

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- 17 Jun 2003, Deutsche Welle: The World's First Underwater Windmill Starts Turning[dead link]

- U.S. Mill Pictures and Information Archived 2021-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Tidal power station Archived 2008-01-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Mill database with over 10000 European mills Archived 2014-01-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Watermills in Norfolk, England

- Mills in Hampshire, England

- Upwey Mill, Weymouth, Dorset Archived 2008-01-07 at the Wayback Machine

- The International Molinological Society (TIMS)

- The Society for the Preservation of Old Mills (SPOOM)