Lobotomy

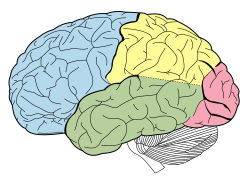

Lobotomy, also known as leucotomy, is a discredited form of neurosurgery that involves severing parts off the brain's prefrontal cortex. It was created in 1935 by António Egas Moniz, a Portuguese neurologist. He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1949 "for his discovery of the therapeutic value of leucotomy in certain psychoses".[1] The operation cut the connections from the pre-frontal cortex (front part of the frontal lobes) to the rest of the brain. At first it seemed a great success, but the operation is now rarely done.

He used the method for certain types of mental illness for which there was no other treatment. He first used it on patients with obsessive behaviour, which they repeated time and again. It was also used to treat other mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and clinical depression.

The problem with lobotomies was that they forever changed a person's personality and behaviour. Sometimes, the results were beneficial: patients which had been violent became calm. But long-term studies, which were not done by Moniz, show some had severely damaged personalities. They often had very little 'drive' and motivation.

Today, antipsychotic drugs, like chlorpromazine, may treat the symptoms of such disorders. Lobotomies are not common today.

Social context

One question is why was such a dramatic surgical technique so widely accepted. It is generally agreed that psychiatrists wanted to find some way of helping thousands of patients in psychiatric hospitals in the twentieth century.[2] Also, those same patients had little power to resist the increasingly radical and even reckless interventions of asylum doctors.[3]

Indications and outcomes

According to the Psychiatric Dictionary in 1970:

Good results are obtained in about 40 percent of cases, fair results in some 35 percent and poor results in 25 percent. The mortality rate probably does not exceed 3 percent. Greatest improvement is seen in patients whose premorbid personalities were 'normal', cyclothymic, or obsessive compulsive; in patients with superior intelligence and good education; in psychoses with sudden onset and a clinical picture of affective symptoms of depression or anxiety, and with behaviouristic changes such as refusal of food, overactivity, and delusional ideas of a paranoid nature.[4]

According to the same source, prefrontal lobotomy reduces:

anxiety feelings and introspective activities; and feelings of inadequacy and self-consciousness are thereby lessened. Lobotomy reduces the emotional tension associated with hallucinations and does away with the catatonic state. Because nearly all psychosurgical procedures have undesirable side effects, they are ordinarily resorted to only after all other methods have failed. The less disorganized the personality of the patient, the more obvious are post-operative side effects. ...[4]

Convulsive seizures are reported as [effects] of prefrontal lobotomy in 5 to 10 percent of all cases. Such seizures are ordinarily well controlled with the usual anti-convulsive drugs. Post-operative blunting of the personality, apathy, and irresponsibility are the rule rather than the exception. Other side effects include distractibility, childishness, facetiousness, lack of tact or discipline, and post-operative incontinence.[4]

Lobotomy Media

The Swiss psychiatrist Gottlieb Burckhardt (1836–1907)

The Estonian neurosurgeon Ludvig Puusepp c. 1920

The pioneer of lobotomies, the Portuguese neurologist and Nobel Laureate António Egas Moniz

Brain animation: left frontal lobe highlighted in red. Moniz targeted the frontal lobes in the leucotomy procedure he first conceived in 1933.

- Lobotomy 1.jpg

Site of borehole for the standard pre-frontal lobotomy/leucotomy operation as developed by Freeman and Watts

References

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1949". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- ↑ The number of patients in psychiatric hospitals was much greater then than now.

- ↑ Porter, Roy 1999. The greatest benefit to mankind: a medical history of humanity from antiquity to the present. Fontana Press: p520

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Hinsie, Leland E. and Campbell, Robert Jean 1970. Psychiatric dictionary. 4th ed, Oxford University Press. p438

Further reading

- Jones W.L. 1983. Ministering to minds diseased: history of psychiatric treatment. London: Heinemann.