Normandy

Normandy (French: [Normandie] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) is a region in northern France. People from Normandy are called Normans. The name Normandy comes from the "Northmen" (Latin: [Northmanni] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), also called Vikings. They came from Scandinavia, and conquered this area in the 9th and 10th centuries. The group of people that settled at Rouen and became the Normans was led by Rollo. Normandy is also famous for being the location of the Allied invasion of France during World War II (See D-Day). The Battle of Normandy was the beginning of the Allied invasion and liberation of Europe from Nazi Germany.

History

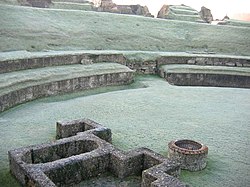

Archaeological evidence, such as cave paintings, show that people lived in Normandy in prehistoric times.[1] The Gouy and Orival cave paintings also show people lived in Seine-Maritime. Many megaliths can be found in Normandy, most of them built in the same way.

Groups of Belgae and Celts, known as Gauls, invaded Normandy in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. Much of our knowledge about this group comes from Julius Caesar’s book de Bello Gallico. Caesar wrote about many groups among the Belgae who lived different areas in agrarian towns surrounded by walls. In 57 BC the Gauls worked together and tried to fight Caesar’s army. They were led by Vercingetorix. The Normans lost an important fight at Alesia. They did not stop fighting until 51 BC, when Caesar finished his conquest of Gaul. Normandy was part of Armorica when it was ruled by Romans.

The duchy of Normandy began in the year 911.[2] Charles the Simple, King of France gave land near Rouen and the lower Seine to Rollo, leader of a band of Vikings. [a][4] This treaty is often called St. Clair-sur-Epte. More land was given in 924 and 933.[2]

The Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror, invaded England in 1066 after King Edward the Confessor died. William the Conqueror thought he should be King of England. But King Harold II had crowned himself king. King Harold's Saxon army and William's Norman army fought at the Battle of Hastings on October 14 1066. King Harold was killed in the battle. On December 25 1066 William was crowned King of England as 'William I'.

The historic duchy is made of two regions of France: Upper Normandy and Lower Normandy. The Channel Islands are part of the duchy of Normandy. But they are not part of France. The whole duchy was not part of France for a long time. In 1205, Philip II of France took away all the French land from King John of England.[5] Then, Normandy was a province of France.

World War II

During the Second World War (1939–1945) Normandy was part of German-occupied France.[6] The town of Dieppe was the site of the unsuccessful Dieppe Raid by Canadian and British armed forces.[7] The Allies (Britain, the United States, and Canada) launched the D-Day landings on 6 June 1944 under the code name 'Operation Overlord'.[8] About 12,000 planes dropped paratroopers before dawn. At dawn the Normandy landings began. Nearly 160,000 Allied soldiers came to the beaches, in about 7,000 ships and landing craft.

The Germans were defending their fortifications above the beaches. Caen, Cherbourg, Carentan, Falaise and other Norman towns had many casualties in the Battle of Normandy. The German defenders fought aggressively but were constantly pushed back. The battle for Normandy continued until the closing of the Falaise pocket.[b][10] The liberation of Le Havre followed. That allowed the breakout of Allied forces into France and finally Germany and was a significant turning point in the war. It led to the restoration of the French government in France. The last bit of Normandy was liberated only on 9 May 1945, at the end of the war un Europe, when the German occupation of the Channel Islands effectively ended.

Geography

The historical duchy of Normandy occupied the lower Seine area, the Pays de Caux and the region to the west through the Pays d'Auge as far as the Cotentin Peninsula. The region is bordered along the northern coasts by the English Channel. There are granite cliffs in the west and limestone cliffs in the east. There are also long stretches of beach in the center of the region. The unique bocage hedges are typical of the western areas of Normandy.[11] The highest point is the Signal d'Écouves at 417 metres (1,368 ft) in the Massif armoricain.[12] Normandy is lightly forested. Eure has the most wooded areas with about 20% being forest.[13] The population of Normandy today is around 3.45 million.

Normandy Media

Bayeux Tapestry (Scene 23): Harold II swearing oath on holy relics to William the Conqueror

Joan of Arc about to be burned at the stake in the city of Rouen, painting by Jules Eugène Lenepveu

Omaha Beach during the Allied invasion of Normandy, mid-June 1944

The island of Mont-Saint-Michel, the most visited monument in Normandy

The Arche and the Aiguille of the cliffs of Étretat

A typical Norman thatched building. This is now a village hall.

Notes

- ↑ English sources including The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle used the names Vikings and Danes interchangeably. Continental sources used the names Swedes, Danes and Vikings interchangeably. Only the Irish sources tried to identify Vikings by their origins. They called Danes Dub-gaill (black foreigners) and Norwegians as Finn-gaill (white foreigners).[3]

- ↑ The Falaise pocket was created by the Allied armies encircling the German army near Falaise.[9] An estimated 10,000 German soldiers were killed, and 50,000 were taken prisoner.[9] Some escaped through the gap left in the lines, but most of them were not combat troops.[9]

References

- ↑ The 20th Century A-GI: Dictionary of World Biography, Volume 7, ed. Frank N. Magill (London; New York: Routledge, 1999), p. 456

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 R. Allen Brown, The Normans and the Norman Conquest (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1998), p. 15

- ↑ Gwyn Jones, A History of the Vikings (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 75–77

- ↑ The Annals of Flodoard of Reims 919–966, ed. & trans. Steven Fanning; Bernard S. Bachrach (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), pp. xx-xxi

- ↑ Maurice Powicke, The Loss of Normandy: 1189 - 1204 ; Studies in the History of the Angevin Empire (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999), p. 283

- ↑ Dominique François, Normandy: From D-Day to the Breakout: June 6-July 31, 1944 (Norwalk, CT: MBI Publishing Company LLC, 2013), p. 12

- ↑ Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1887-1976: A Selected Bibliography, ed. Colin F. Baxter (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999), p. 32

- ↑ The Normandy Campaign 1944: Sixty Years On, ed. John Buckley (London; New York: Routledge, 2006), p. 170

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 John N. Bradley, The Second World War: Europe and the Mediterranean (New York: Square One Publishers, 2002), pp. 336, 338

- ↑ Russell Hart, Clash of Arms: How the Allies Won in Normandy (Boulder: Rienner, 2001), pp. 391–92

- ↑ Judy Smith, Holiday Walks in Normandy (Wilmslow: Sigma Leisure, 2001), p. 63

- ↑ Barbara Eperon, Normandy Picardy & Pas De Calais (Lincolnwood, IL: Passport Books, 1997), p. 76

- ↑ Judy Smith, Holiday Walks in Normandy (Wilmslow: Sigma Leisure, 2001), p. 119