Cro-Magnon

The earliest known Cro-Magnon remains are between 35,000 and 45,000 years old,[1][2] based on radiometric dating. The oldest remains, from 43,000 – 45,000 years ago, were found in Italy[2] and Britain.[3] Other remains also show that Cro-Magnons reached the Russian Arctic about 40,000 years ago.[4][5]

Cro-Magnons had powerful bodies, which were usually heavy and solid with strong muscles. Unlike Neanderthals, which had slanted foreheads, the Cro-Magnons had straight foreheads, like modern humans. Their faces were short and wide with a large chin. Their brains were slightly larger than the average human's is today.[6][7]

Naming

The name "Cro-Magnon" was created by Louis Lartet, who discovered the first Cro-Magnon skull in southwestern France in 1868. He called the place where he found the skull Abri de Cro-Magnon.[8] Abri means "rock shelter" in French;[8] cro means "hole" in the Occitan language;[9] and "Magnon" was the name of the person who owned the land where Lartet found the skull.[10] Basically, Cro-Magnon means "hole on Magnon's land."

This is why scientists now use the term "European early modern humans" instead of "Cro-Magnons." In taxonomy, the term "Cro-Magnon" does not mean anything.[1]

Cro-Magnon life

- Used bones, shells, and teeth to make jewelry

- Spun, dyed, and tied knots in flax, to make cords for their tools, make baskets, or sew clothing

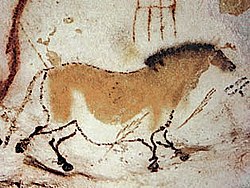

Like most early humans, the Cro-Magnons mostly hunted large animals. For example, they killed mammoths, cave bears, horses, and reindeer for food.[11] They hunted with spears, javelins, and spear-throwers. They also ate fruits from plants.

The Cro-Magnons were nomadic or semi-nomadic. This means that instead of living in just one place, they followed the migration of the animals they wanted to hunt. They may have built hunting camps from mammoth bones; some of these camps were found in a village in Ukraine.[12][13] They also made shelters from rocks, clay, tree branches, and animal skin (leather).[13]

Cro-Magnon Media

Bohunician scrapers in the Moravian Museum, Czech Republic

Map of the distribution of the main Aurignacian sites before the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)

LGM refugia, c. 20,000 years ago* Solutrean* Epigravettian

Skull of the Abri Pataud woman

Female face, carved ivory, Dolní Věstonice, Gravettian, c. 26,000 BP

Location of the Zlatý kůň fossil with an age of at least ~40,000 years, that yielded genome-wide data

Magdalenian bone barbed point from Cueva de Santimamiñe, in Bilbao Archaeology Museum

Music played with a replica of the 33,000-year-old Izturitz flute found in the Isturitz and Oxocelhaya caves

Related pages

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Fagan, B.M. (1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 864. ISBN 978-0-19-507618-9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2011, Benazzi S.; Douka, Katerina; Fornai, Cinzia; Bauer, Catherine C.; Kullmer, Ottmar; Svoboda, Jiří; Pap, Ildikó; Mallegni, Francesco; Bayle, Priscilla; Coquerelle, Michael; Condemi, Silvana; Ronchitelli, Annamaria; Harvati, Katerina; Weber, Gerhard W.; et al. (2011). "Early dispersal of modern humans in Europe and implications for Neanderthal behaviour". Nature. 479 (7374): 525–8. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..525B. doi:10.1038/nature10617. PMID 22048311. S2CID 205226924.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Higham T; Compton T; et al. 2011 (2011). "The earliest evidence for anatomically modern humans in northwestern Europe". Nature. 479 (7374): 521–4. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..521H. doi:10.1038/nature10484. PMID 22048314. S2CID 4374023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Pavlov P; Svendsen JI; et al. 2001 (2001). "Human presence in the European Arctic nearly 40,000 years ago". Nature. 413 (6851): 64–7. Bibcode:2001Natur.413...64P. doi:10.1038/35092552. PMID 11544525. S2CID 1986562.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Svendsen JI; Pavlov P 2003 (2001). "Mamontovaya Kurya: An enigmatic, nearly 40 000 years old Paleolithic site in the Russian Arctic" (PDF). Trabalhos de Arqueologia. 33 (6851): 109–120. Bibcode:2001Natur.413...64P. doi:10.1038/35092552. PMID 11544525. S2CID 1986562. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 14, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Cro-Magnon". Britannica.com. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Stringer C. 2012. What makes a modern human. Nature 485 (7396): 33–35. [1]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 (in French) "Mode de vie au paleolithique superieur". archive.wikiwix.com (cached). Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Geuljans, Robert (July 5, 2011). "Cros". etymologie-occitane.fr. Dictionnaire Etymologique de la Langue D’Oc. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Hitchcock, Don (January 3, 2016). "The Cro-Magnon Shelter". Don’s Maps: Resources for the study of Palaeolithic / Paleolithic European, Russian and Australian Archaeology / Archeology. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Bones from French Cave Show Neanderthals, Cro-Magnon Hunted Same Prey". ScienceDaily. University of Washington. September 23, 2003. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Dan Koehl. "The Cro Magnon man (Homo sapiens sapiens) Anatomically Modern or Early Modern Humans". Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Pidoplichko, I.H. (1998). Upper Palaeolithic dwellings of mammoth bones in the Ukraine: Kiev-Kirillovskii, Gontsy, Dobranichevka, Mezin and Mezhirich. Oxford: J. and E. Hedges. ISBN 0-86054-949-6.