Elementary particle

In physics, an elementary particle or fundamental particle is a particle that is not made of other particles.

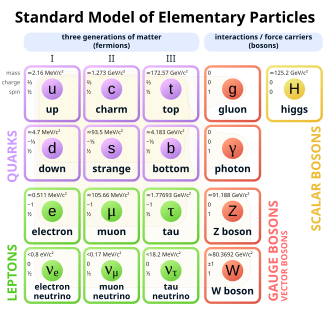

An elementary particle can be one of two groups: a fermion or a boson. Fermions are the building blocks of matter and have mass, while bosons behave as force carriers for relations between fermion and some of them have no mass.[1] The Standard Model is the most accepted way to explain how particles behave, and the forces that affect them. According to this model, the elementary particles are further grouped into quarks, leptons, and gauge bosons, with the Higgs boson having a special status as a non-gauge boson.

Of the particles that make up an atom, only the electron is an elementary particle. Protons and neutrons are each made of 3 quarks, which makes them composite particles, particles that are made of other particles. The quarks are bound together by the gluons. The nucleus has boson pion fields responsible for the strong nuclear force binding protons and neutrons against the electrostatic repulsion between protons. Such virtual pions are composed of quark antiquark pairs again held together by gluons.

There are three basic properties that describe an elementary particle: ’mass’, ’charge’, and ’spin’. Each property is assigned a number value. For mass and charge the number can be zero. For example, a photon has zero mass and a neutrino has zero charge. These properties always stay the same for an elementary particle.

- Mass: A particle has mass if it takes energy to increase its speed, or to accelerate it. The table to the right gives the mass of each elementary particle. The values are given in MeV/c2s (that is pronounced megaelectronvolts over "c" squared), that is in units of energy over the speed of light squared. This comes from special relativity, which tells us that energy equals mass times the square of the speed of light. All particles with mass produce gravity. All particles are affected by gravity, even particles with no mass like the photon (see general relativity).

- Electric charge: Particles may have positive charge, or negative, or none. If one particle has a negative charge, and another particle has a positive charge, the two particles are attracted to each other. If the two particles both have negative charge, or both have positive charge, the two particles are pushed apart. At short distances, this force is much stronger than the force of gravity which pulls all particles together. An electron has charge -1. A proton has charge +1. A neutron has an average charge 0. Normal quarks have charge of ⅔ or -⅓.

- Spin: The angular momentum or constant turning of a particle has a particular value, called its spin number. Spin for elementary particles is one or ½. The spin property of particles only denotes the presence of angular momentum. In reality, the particles do not spin.

Mass and charge are properties we see in everyday life, because gravity and electricity affect things that humans see and touch. But spin affects only the world of subatomic particles, so it cannot be directly observed.

Fermions

Fermions (named after the scientist Enrico Fermi) have a spin number of ½, and are either quarks or leptons. There are 12 different types of fermions (not including antimatter). Each type is called a "flavor". The flavors are:

- Quarks: up, down, charm, strange, top, bottom. Quarks come in three pairs, called "generations". The 1st generation (up and down) is the lightest and the third (top and bottom) is the heaviest. One member of each pair (up, charm and top) has a charge of ⅔. The other member (down, strange and bottom) has charge -⅓.

- Leptons: electron, muon, tau, electron neutrino, muon neutrino, tau neutrino. The neutrinos have charge 0, hence the neutr- prefix. The other leptons have charge -1. Each neutrino is named after its corresponding original lepton: the electron, muon, and tauon.

Six of the 12 fermions are thought to last forever: up and down quarks, the electron, and the three kinds of neutrinos (which constantly switch flavor). The other fermions decay. That is, they break down into other particles a fraction of a second after they are created. Fermi-Dirac statistics is a theory that describes how collections of fermions behave.

Bosons

Bosons, named after the Indian physicist Satyendra Nath Bose. Bosonic particles have spin 1 (integral spin). Although most bosons are made of more than one particle, there are two kinds of elementary bosons:

- Gauge bosons: gluons, W+ and W- bosons, Z0 bosons, and photons. These bosons carry 3 of the 4 fundamental forces, and have a spin number of 1;

- Gluon: Gluons are massless and chargeless particles, and they are the carriers of the strong force interaction. They, along with quarks, join together to make composite particles called hadrons, which include protons and neutrons.

- W and Z bosons: W and Z bosons are particles that carry the weak force. The W boson has a matter particle (W+) and an antimatter particle (W-), whereas the Z boson is its own anti-particle. The W boson is produced in beta decay, but almost immediately turns into a neutrino and an electron. The W and Z bosons were both discovered in 1983.

- Photon: Photons are massless and chargeless particles that carry electromagnetic force. Photons can have a certain frequency that determines what electromagnetic radiation they are. Like all other massless particles they travel at the speed of light (300,000 km/s).

- Higgs boson: Physicists believe that massive particles have mass (that is, they are not pure bundles of energy like photons) because of the Higgs interaction.

The photon and the gluons have no charge, and are the only elementary particles that have a mass of 0 for certain. The photon is the only boson that does not decay. Bose-Einstein statistics is a theory that describes how collections of bosons behave. Unlike fermions, it is possible to have more than one boson in the same space at the same time.

The Standard Model includes all of the elementary particles described above. All these particles have been observed in the laboratory.

The Standard Model does not talk about gravity. If gravity works like the three other fundamental forces, then gravity is carried by the hypothetical boson called the graviton. The graviton has yet to be found, so it is not included in the table above.

The first fermion to be discovered, and the one we know the most about, is the electron. The first boson to be discovered, and also the one we know the most about, is the photon. The theory that most accurately explains how the electron, photon, electromagnetism, and electromagnetic radiation all work together is called quantum electrodynamics.

Elementary Particle Media

References

- ↑ Sylvie Braibant; Giorgio Giacomelli; Maurizio Spurio (2012). Particles and fundamental interactions: an introduction to particle physics (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-94-007-2463-1.

Releted pages

+{{{1}}}−{{{2}}}